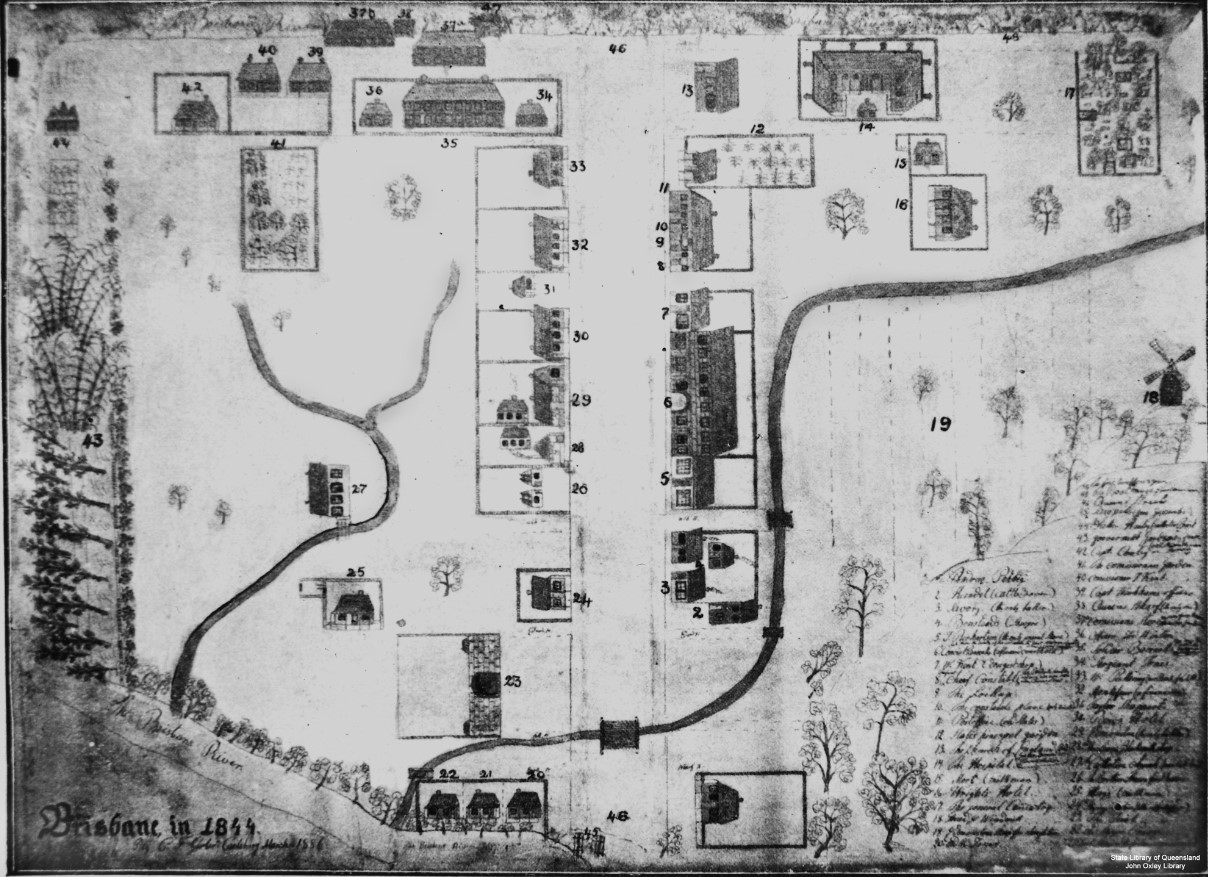

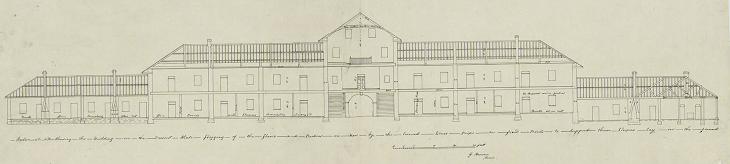

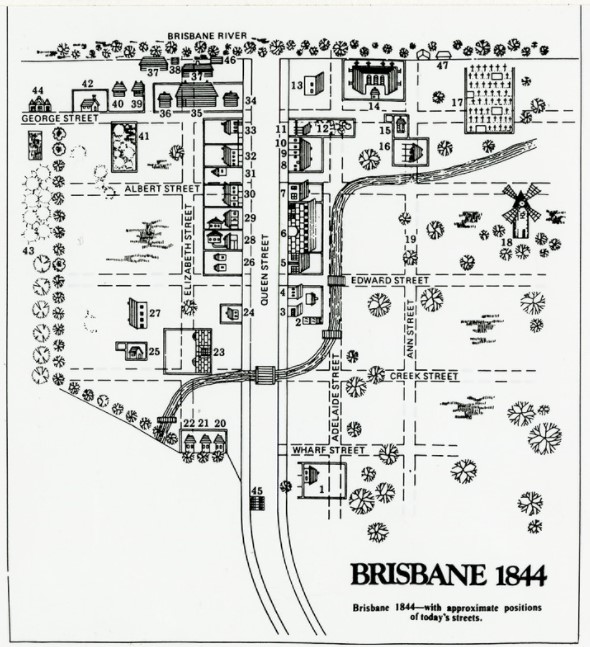

The Sketch Map of Brisbane Town in 1844, and the stories behind it.

A rough, sketched map of Brisbane town in 1844 reposes in the John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. It is attributed to Carl Friedrich Gerler, who arrived in Brisbane as a missionary to the Zion Hill establishment in 1844. The buildings and features are numbered, with a handwritten key on the lower right-side. Streams and creeks, long erased by progress, wind their way around the township, and the Windmill is depicted with its sails intact.

It’s rudimentary and darkened with age, but does give an idea of the locations and the shapes of the buildings there. The sketches of the gaol and convict barracks are easily recognisable from the other plans and drawings available.

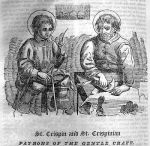

The key to the drawing has been added to the descriptors on the website, and reads:

A modern version of the map, showing the approximate locations of the buildings against today’s streets, has been created (it’s at the end of the post). Several places and people were hard to identify from the map key, due to the translation of the faded 170 year old cursive, but it is remarkable how many of them were involved in the big events of the time:

1846: October 20 – Murders of Andrew Gregor and Mrs Mary Shannon by indigenous people at Pine River. Various suspects were named – Jemmy, Millbong Jemmy, Jackey Jackey, Moggy Moggy, Dick Ben, Make-i-light and Dundalli.

1846: December 20: Police shot at indigenous people at York’s Hollow (Herston), looking for Jackey Jackey.

1847: January: Inquiry into York’s Hollow shooting ordered by Governor.

1848: March: Murder of Robert Cox at Kangaroo Point. William Fife convicted and hanged.

1849: November 28: Soldiers fired at indigenous people at York’s Hollow, after a reported cattle theft.

The People and Places of Old Brisbane

1. Andrew Petrie

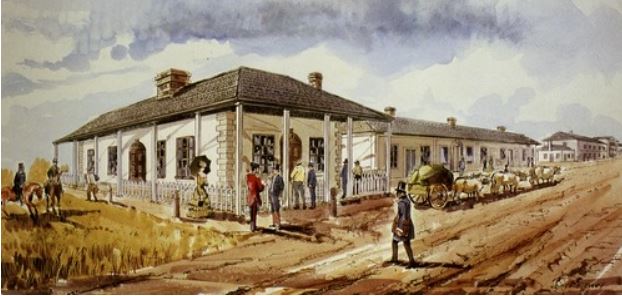

Andrew Petrie (1798–1872) came to Brisbane in 1837 as Clerk of Works, building his home on the corner of Queen and Wharf streets, after a miserable stay in the only building available for the family at that time – the long-abandoned Female Factory. In a moment of Scottish frankness, he referred to the place as “that hole.”

For his new home and business, his choice of location was masterly – he had access to the river at a convenient site for docking and wharves, and was still close enough to the administrative part of town to supervise his firm’s renovations and construction works. Before losing his sight in 1848, he had established a successful architecture and building company, explored the coastal territory, climbed Mt Beerwah, brought Wandi and Duramboi back to Brisbane, located the Mary River, and set up his family in a tradition of craftsmanship and civic service.

Even without sight, Petrie was able to carry on business, tapping buildings with his cane to determine if the structures were true. He encouraged his sons to learn about the indigenous people of Moreton Bay, and to treat them with respect and cooperation. John and Thomas Petrie were able to speak indigenous languages, and Thomas spent much of his life recording a culture that was being decimated before his eyes.

In the 1840s, the Petrie family accommodated and entertained distinguished visitors to the township, who, understandably, shied away from the rustic charms of the few inns of early Brisbane.

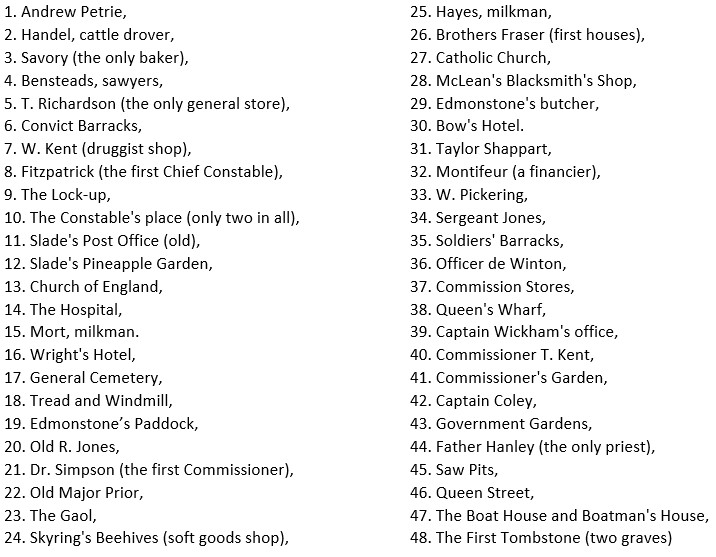

2. Handel, Cattle Drover

There was no Handel, bullock-drover, to be found in the records, although a Joseph Mandell, bullock-driver, was working around the Colony, in the Brisbane, Darling Downs and Ipswich areas at the time. It was a hard job, providing the only heavy land transport available in those pre-railway days. Few roads had been carved out of the bush, and getting dozens of slow-moving, yoked beasts to pull heavy loads vast distances required rare skill and patience. And a vocabulary that tended to be unfit for mixed company.

In October 1849, Joseph Mandells (a drayman) was committed to take his trial in Sydney with a man named James Dennis, for stealing tallow and sheepskins from a boiling-down establishment at a place only referred to as The Swamp by the local press. They had been employed to take the goods from The Swamp (later identified as Gowrie Station) to Ipswich.

It was two years before the existence of a Supreme Court in this part of the Colony, so the two draymen were sent to Sydney for trial, and earned three years hard labour on the roads for their misdeeds.

3. Savory, the only Baker

The Brisbane baker of the 1840s was a Frenchman named Henry Savary, a cook and confectioner who had arrived free to New South Wales in 1837, but blotted his copybook almost immediately on arrival. Sentenced to six months for embezzlement, he was then released to hired service, which he promptly fled. Once that little bit of unpleasantness was resolved, M Savary took his culinary talents to the remote northern parts of New South Wales.

In Brisbane Town, he found a small population weary of a life without properly baked bread and pastries, and he prospered. Unskilled convict servant cooks could not compete with the delicacies offered by a real French baker. M Savary found himself with a thriving business, and set about expanding, but hints of the old Brisbane kept appearing. Working on an extension to his premises, Henry Savary discovered a skeleton with convict ankle chains in September 1846.

Old Brisbane was evident also in the problems Savary experienced with indentured convict servants. In a few short years, the local Magistracy dealt with John Bristow aka Johnny the Baker (drunk and neglectful of his duty – one month), William King (drunk and insolent – one month), Andrew Grieg (incompetent, his wages claim dismissed) and Henry Newbould (a “scamp”, settled at hearing).

Not shy of expressing himself, Savary also litigated with James Newbould (assault, stemming from Savary calling his son Henry a scamp), and William Clark (assault, after Clark and his wife were found guilty of threatening and abusive language). Mr Clark was described by the Courier as a Knight of St Crispin (shoemaker).

On Saturday, 16 June 1846, Henry Savary announced to the township that he was leaving Brisbane, and required all outstanding debts to be repaid before his departure, please and thank you. He found another good living in Ipswich, taking over the Shamrock Inn, offering the best wines and table in the Northern Districts. In 1851, he was again renovating and expanding his business. Savary died at his establishment in July 1852, aged only 40, following a short illness.

4. Bensteads, Sawyers

John Benstead was the Sawyer working at Brisbane in the 1840s. The spelling of the family name varied between Benstead, Binstead, and Bensted, making it hard to trace their movements. Sadly, one event in their lives was easy to find. On 16 April 1848, his son James drowned in the Brisbane reservoir.

“MELANCHOLY ACCIDENT. – A poor little fellow, the son of a Mr. John Benstead, of this town, aged six years, fell into the town reservoir on Sunday afternoon last, and before assistance could be procured was unfortunately drowned. Several of his playmates were present at the time but were too young to render him any aid.“

Little James’ death was registered under the name of Binstead, and after that, references to the family in Brisbane cease. Perhaps they needed a fresh start elsewhere. The Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages records a John Binstead passing away in country Queensland in 1857.

5. T Richardson (the only General Store)

John Richardson (J not T – handwriting) had a prosperous business next door to the Convict Barracks, and offered the public “Woolpacks, sheepshears, and tarpawlings,” together with an array of goods associated with the very complicated matter of getting dressed in the 1840s, to wit:

Moleskin trousers, cord ditto, pilot-cloth and Holland coats, Waistcoats in quilting, valentia, and figured satin Blue cloth jackets, and fancy cloth trousers Striped, twilled, and regatta shirts, Blue and red serge, and merino, and worsted ditto Black and coloured velveteens, cords, and moleskins Brown, white, plain, and diagonal drills, grandrills, and jeans, Plain and fancy tweeds, and plaid stuffs for dresses Blankets, flannels, white and coloured counterpanes Canvas, Osnaburg, ticks, and toweling Hollands, diapers, linens, and lawns. Light and dark prints, and navy blues, A large stock of ginghams in fancy and clan tartans.

John Richardson’s list of civic activities and accomplishments verged on the exhausting – Elector of North Brisbane, Committee member of the Benevolent Society, and Committee member for raising relief for the starving poor of Scotland and Ireland. Richardson led subscriptions for the establishment of a General Hospital at Brisbane, and lobbied successfully for a Customs House at Brisbane.

Civic improvements weren’t the only current issue on John Richardson’s mind. He sought subscriptions for a £40 reward for the apprehension of the four indigenous men “who murdered Mr Gregor and Mrs Shannon” – no “allegedly” or “suspected” here. In this case, his civic zeal sounded remarkably like a call to vigilantism.

6. The Convict Barracks

Built by in the 1820s the unfortunate men it was to house, the Convict Barracks complex dominated Queen Street for decades. After the convicts left in 1839-40, it was pressed into service as an immigration depot, police office and later a court-house. With each new use, money for rudimentary repairs had to be reluctantly liberated from the purse of the Colonial Secretary. The distinctive archway was the site of convict floggings at the triangle in the penal colony days.

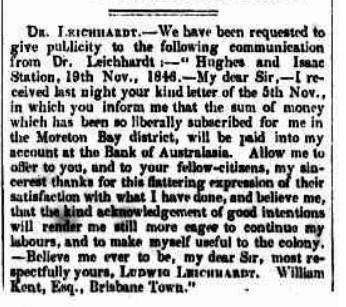

7. W. Kent (druggist shop)

William Kent, the chemist in Brisbane was another successful Colonist who became very active in local affairs. He knew Dr Ludwig Leichhardt, and raised subscriptions for the good Doctor’s expeditions. He also sought subscriptions for a new road over “D’Acquilar’s Range” (now known as the D’Aguilar Range and pronounced, confusingly, as “Dee-yag-yul-ah” by locals).

Prominent citizens of a small settlement tended to find themselves in the midst of any major event in town. The biggest news stories at the time were the two York’s Hollow shootings (1846 and 1849) and the murder of Robert Cox at Kangaroo Point. Many of the people on the 1844 map were witnesses to at least one of these occurrences.

In late 1846, there was a shooting incident involving police and the indigenous people at York’s Hollow (where the Victoria Park golf course is today). The Police were trying to apprehend Jackey Jackey – a suspect in several murders – in York’s Hollow, where a corroboree was in progress. Shots were fired, and a young indigenous woman named Kitty was reported to have died. Depending on the witness, Kitty either died in childbirth, or from wounds inflicted by a police gun, or from being beaten about the head by a waddie. William Kent gave evidence to hearing about all three of her possible causes of death.

8. Fitzpatrick (the first Chief Constable) (plus 9 Lock-up and 10 Constable’s place)

William Fitzpatrick was responsible for law and order in the small settlement, and he did not get along with the Moreton Bay Courier, which portrayed him as blustering, ill-tempered and toothless.

When not offering himself up to journalistic ridicule, Fitzpatrick investigated the Cox-Fife murder and both York’s Hollow shootings. The second shooting, in 1849, cost him his career.

In early January 1847, he gave corroborative evidence of his constables about the first York’s Hollow incident, deposing that the constable had fired blindly in the night after a suspected indigenous murderer, Jackey Jackey, escaped from custody. No-one knew if Jackey Jackey had been hit by the bullet, but he had made good his escape.

In March 1848, Fitzpatrick was summoned to take charge of a murder scene the like of which no-one in the Colony had seen before:

“Mr. Fitzpatrick, the Chief Constable, stated that on being informed on Sunday morning that a man had been murdered at Kangaroo Point, he proceeded thither, and observed the body lying on the river bank, in two separate parts—the head, or trunk part, six or seven yards from the lower part; the head was deficient; the body was severed across the loins; and bore the mark of a deep cut on the right side of the breast, severing the ribs; he also observed a deep cut on the left side, but not so extensive; the body was below high water mark, but not so low as low water mark. After having the body removed, he proceeded to make enquiries, and went to Mr. Sutton’s.”

Proceeding to Sutton’s Inn, Fitzpatrick found a large group of understandably agitated people. They gave him various accounts of who the dismembered victim might have been. Sutton suggested that it was a sawyer named Robert Cox, who had been very drunk the night before, and was locked in the kitchen with the cook, William Fife, to sleep it off. At some point during the night, Cox was said to have gone out of the room, giving the key to the cook and leaving for places unknown. After midnight, the Fife went to Sutton for a candle and a glass of ale, telling his boss that he wanted to finish his work.

When the head of the dead man was located, it was positively identified as that of Robert Cox. Fitzpatrick was told that Sutton’s servant, William Fife, had known Cox during their convict days at Moreton Bay. The Chief Constable took several men at the location into custody, noticing that Fife had blood on his shirt, and had not asked why he was being arrested. Sutton opined that it looked like Fife had murdered Cox. Fife was charged, and eventually hung for the crime, protesting his innocence to the last. (Serious historians and amateur sleuths alike are still debating his innocence, and the identity of the true culprit.)

York’s Hollow 1849

On the night of the 28th November 1849, John Petrie was alerted that several of his bullocks were missing, and that the local indigenous people were being blamed. Petrie sent word to the authorities, then proceeded with his brothers to the area where the indigenous people were camped, and got their help to look for the bullocks. After searching about the York’s Hollow bush for a while, they heard shots, returned to the camp. The Petries found soldiers there, who claimed that one of the indigenous people had thrown a boomerang, and that they had fired in response. No-one could locate any injured at first, and Petrie told the soldiers to stop firing, and all parties decamped. Several injured indigenous men were later treated in the hospital.

When Chief Constable Fitzpatrick was alerted to the situation, he ordered all of his constables to York’s Hollow, and to alert Dr Ballow in his capacity as a magistrate. He did not enter the fray himself.

“In the course of the investigation, the police magistrate severely censured the chief constable, who, it appeared, was in bed at the time when the alarm was given, and who had not taken any active part in the subsequent proceedings, further than issuing his orders to the constables. The chief constable defended himself by stating that he had been up very late on Tuesday night, on duty, and that he was too ill to go out when the constables came to him. Copies of the proceedings, with the report of the police magistrate thereon, were forwarded to Sydney by the last steamer.“

As Fitzpatrick saw it, “on the representation of Captain Wickham, the Police Magistrate, to his Excellency the Governor, I was dismissed from the office of Chief Constable, on an alleged charge of neglect, or misdirection, on the night of the 28th November last, when an affray took place between the military and the blacks, the consequences of which, although they (the military) were ordered out by a magistrate, are fastened on me.”

Fitzpatrick travelled to Sydney, but was not given a hearing. A petition signed by most of the residents of Brisbane, asking that he be given at least a chance to defend himself, was politely accepted and promptly ignored. Even the Courier admitted that the former chief should have had that opportunity.

Despite campaigning for reinstatement, Fitzpatrick was replaced by Samuel Sneyd, who enjoyed a long career in law enforcement at Brisbane. The former chief, not one to let the grass grow, decided to go into business as a grocer and general dealer, and had already opened premises in Queen Street when the final “no” issued from Sydney.

11. Slade’s Post office and 12. Slade’s Pineapple Garden

George Milner Slade was the proprietor of the post-office, which sat in the same group of buildings as the Chief Constable and the lockup. To the side (12), he kept his pineapple garden, growing a delicacy that flourished in this strange, subtropical place.

Slade had been in the military before taking up his work in Brisbane Town, and held a remarkable number of public offices with distinction. In the Military, he had been Paymaster of the 60th Regiment in the West Indies; when that unit went to Sydney, Slade was Coroner for Sydney, Secretary to the Australian Agricultural Company, Commissioner of Assignments, then Clerk of the Bench at Moreton Bay, Registrar of the Court of Petty Sessions at Brisbane and Postmaster.

In 1846, having experienced a turn of ill-health, he applied for three months’ leave of absence – a tortuous process that involved sending a letter by steamer and waiting for a reply by same – and revealed that in twenty-seven years of public service, he had not had a day’s absence for any reason. Happily, his administrative masters approved this leave, and Slade was able to take a vacation and return to Moreton Bay, apparently restored to health.

Mr Slade passed away suddenly in April 1848 at the age of 63. On the last day of his life, he had made up the mail for the steamer to Sydney, before leaving the town devastated by his loss.

13. The Church of England

The first Anglicans in Brisbane Town worshipped in “a ruinous building, attached to the lumber yard at Brisbane Town.” The Rev John Gregor struggled with variously, a tendency of some locals to prefer ungodly carousing to sermons, a tendency of some other locals to prefer the more stringent forms of Protestantism, and the progress of a purpose-built Catholic church (St Stephen’s).

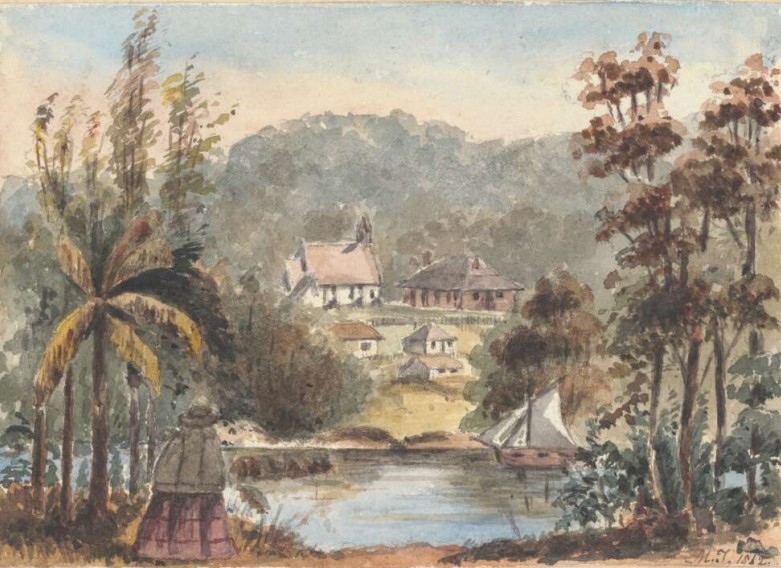

Initially, the ruinous building was repaired and the result was the first St. John’s (left), at what is now the intersection of Queen street and North Quay. In the next years, the church would be further renovated, grow in congregation, and then relocate as the present St John’s Cathedral in Ann Street.

Rev John Gregor did not live to see it flourish, however. He died by drowning at Nundah in January 1848, having spent the last years of his life unhappily – struggling against lack of funds to minister to the parishes of Brisbane and Ipswich, and mourning the death of his brother Andrew, murdered at Pine River in 1846.

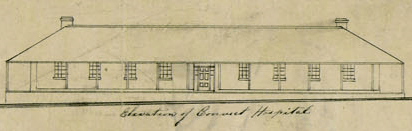

14. The Hospital

The first Brisbane Hospital was a convict building, erected by its intended patients during Captain Logan’s tenure as Commandant in the late 1820s. The building, renovated at bare minimum expense by subsequent New South Wales Governors, survived in use as a hospital until there could be a larger institution built after Separation.

The first Superintendent was Dr William Cowper, who worked with a couple of convict wardsmen day and night, through outbreaks of dysentery and ophthalmia in the convict population, managing to treat hundreds of people at a time, all day and night. There were few proper medical supplies, and Cowper grew tired of having to beg for basic items from Sydney. It’s a testament to his skill that so few of his hundreds of patients died. He also had to read Divine Service to the convicts on Sundays, lest he have a moment of spare time. It’s hardly a surprise that when a relieving doctor came to Moreton Bay, he found Cowper to be a foul-tempered, chain-smoking grog-drinker. Cowper left after a scandal, involving getting into the Female Factory (then in Queen Street) and having a rip-roaring drinking session with female convicts.

As the penal colony closed, the hospital had to adapt to caring for a growing civilian population. It was already evident in the 1850s that the old building would not be sufficient. In addition to consultations and surgery, the Hospital had to operate as a Benevolent Asylum, providing relief to the poor and the elderly. For many decades, it was run on a subscription system, whereby those who could afford a year’s subscription helped fund the institution and cover the costs of treating paupers. The idea of a public hospital providing free medical care would not take hold until the turn of the 20th century.

15. Mort, Milkman

Despite the unusual name, Mr Mort proved elusive. There was a Henry Mort at Cressbrook Station from 1846, trading vast amounts of livestock, and who eventually became a JP on the Bench. Another Mr Mort was a merchant in Sydney, prone to extravagantly worded advertising. It’s unlikely that “Mort, Milkman” was either person, as managing to rise from the hard work of delivering lukewarm raw milk in a horse-drawn cart at dawn to the peaks of mercantile success in two years would be an achievement unrivalled in the history of commerce.

“In soliciting a continuance of the support which his weekly sales have received, Mr. Mort would call attention to the very low scale of charges now adopted, and further to the fact, that from the competition created by the attendance of all classes of buyers, this mode of sale possesses advantages over any other, and at all times ensures the extreme market rates of the day; besides enabling the settler to close his transactions on an average within twenty-four hours of the arrival of his Wool and Tallow.” Nope, with all due respect to the Milkman, I don’t think it’s him.

In Part 2 – some very fancy people, some hard-working people and some surprising fortunes won and lost.

Modern version of Gerler’s Map.

1 Comment