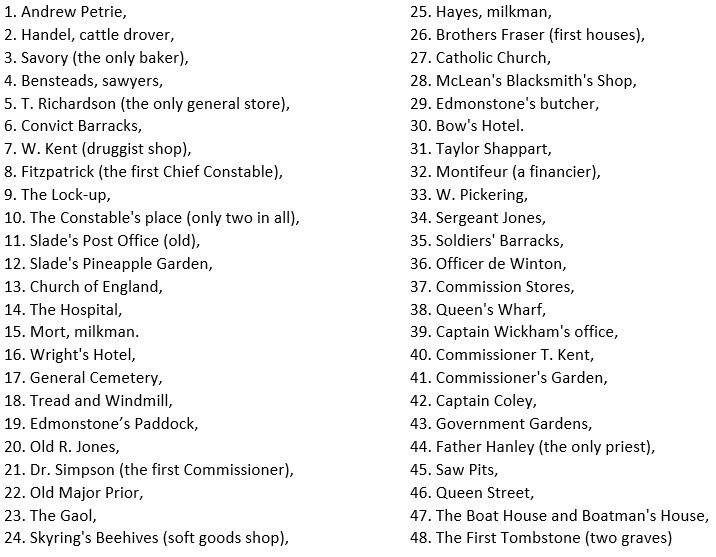

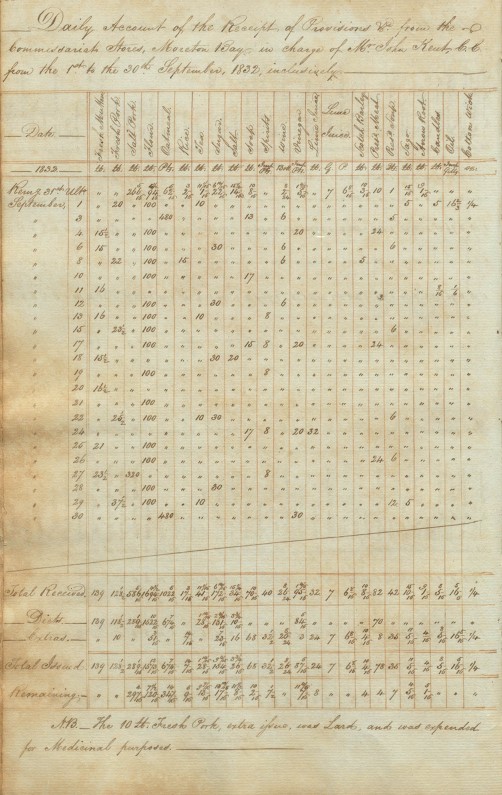

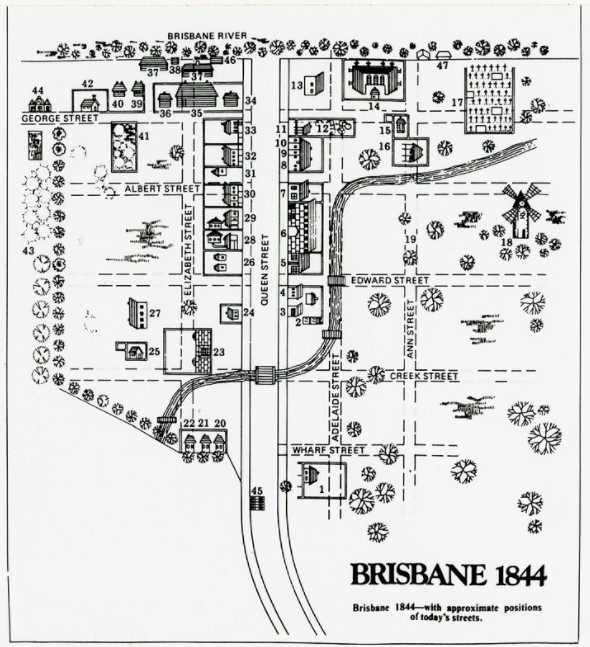

The Sketch Map of Brisbane Town in 1844, and the stories behind it.

31. Taylor Shappart

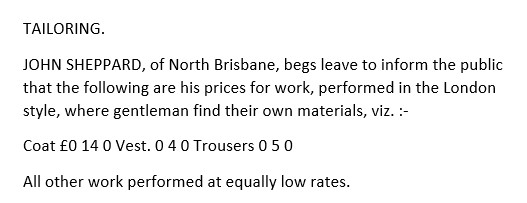

There was no Taylor Shappart in Brisbane in 1844. There was a tailor, John Sheppard, who lived and worked at Brisbane at the time, and later moved to Ipswich. I suspect that between the Gerler’s understanding of English names and his handwriting, Tailor (John) Sheppard became Taylor Shappart.

John Sheppard’s tailoring business sat between the larger establishments of David Bow’s Victoria Hotel and Montefiore and Graham in Queen Street. Sheppard seems to have been an unassuming chap, to whom unpleasant and dramatic things tended to happen.

In February 1847, John Sheppard discovered that his employee Henry Litherland had made off with one pound eight shillings of his money. Worse still, Sheppard found that his wife and Litherland had “an illicit connexion,” of which he had, in the coy term used by the Courier “ocular demonstration.” In other words, he saw them.

Distraught, Sheppard took a pair of shears and ran out of the house in hot pursuit of his fleeing, cheating wife. Litherland had called for the police, who succeeded in restraining Sheppard before he could do something he would regret.

With Sheppard in the lock-up, Litherland and Mrs Sheppard went back to the tailoring shop and took everything they could carry away to the home of a Mr Lynch, including an order for payment to Sheppard by Colin Campbell, Esq. Litherland presented the bill to Campbell, who paid it in cash.

When the Court rose the following morning, Sheppard was released from the lock-up and went home to his shop, to find a lot of property missing, including the bill for Campbell. He went to Campbell, who informed him that the bill had been paid to Litherland. His next stop was the police office, this time as a complainant.

The Bench having heard the evidence said, that it was a very gross case, and they should commit the prisoner (Litherland) to take his trial for the offence.

Moreton Bay Courier.

John Sheppard remained in Brisbane, to pick up the remains of his life and business.

In 1854 John Sheppard was listed as a freeholder in Ipswich, and continued his tailoring business there. He also continued his run of bad luck. Michael Doran came to him to have a coat made up, and after one of his visits, Sheppard discovered that four yards of cloth had disappeared. The police traced the cloth to Doran, who claimed that he had bought it at another store. This was disproved, and Doran received six months with hard labour at Parramatta Gaol for his misdeeds.

Twenty years later, an old and broken man took an “inordinate dose of strychnine,” and died in agony. John Sheppard was 72 years old. His three children and grown up and moved away, his wife (the same one, one wonders?) had left him three weeks earlier, and he had a fondness for drink in very large quantities. Dr Dorsey, another old Queenslander, had been sent for by the police but was unable to save Sheppard.

32. Montifeur (a financier)

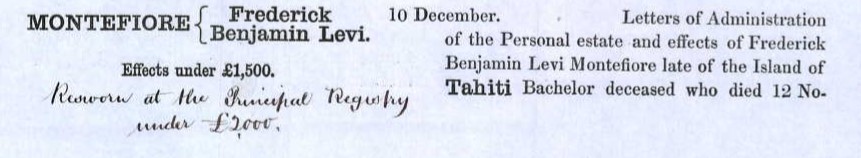

The name Montefiore had been known throughout Europe in banking and diplomatic circles for hundreds of years. One member of that family, Jacob Levi Montefiore (1819 – 1885) established a business partnership with Scottish financier, Robert Graham in Sydney in the 1840s. When the company expanded to Moreton Bay, it was assumed by those in north that Graham would operate the Brisbane branch. Instead, the Montefiores moved to Brisbane. It seems that Jacob Levi Montefiore came to start things up in the mid-1840s, but a new name starts to appear after that – Frederick, or FBL Montefiore. This was young Frederick Benjamin Levi Montefiore, who from 1847 took over the reins. He became an elector for Stanley County, subscribed to the Scottish and Irish Relief Fund, and took to commerce with a will.

In 1849, Frederick Montefiore travelled to Sydney and then on to Tahiti, presumably to expand the family business there. He died in 1853 at Papeete. He was not married, and his age was reported as being about 26, although his date of birth varies in the records, and he may have been closer to 30. His brother Edward Levi Montefiore, his executor, also had interests in Australia, although he lived mainly in Paris until his own death in 1907.

33. W. Pickering

William Pickering was another quiet high achiever in Colonial Brisbane. His life and impact is best summed up by his obituary in the Brisbane Courier in 1868.

IN another column is recorded the death of Mr. William Pickering, one of the Official Assignees of the colony. this circumstance will be deeply regretted by many, as the deceased, though in his private life, one of the most quiet and least conspicuous of our citizens, had, in an unostentatious way, entitled himself to the respect and esteem of all. His death will leave a gap in the number of the few now amongst us who knew Brisbane in its extreme infancy.

Mr. Pickering came to the colony in 1842 or ’43, and prior to his obtaining the office of Official Assignee, which was about the date of Separation, he was in business as a merchant in partnership with the late Captain Coley. Mr. Pickering had not enjoyed robust health for some years past, having been subject to apoplectic fits. During the last few days, he had been confined to his house, but it was not expected till within a very short time of his demise that that illness would be his final one.

34. Sergeant Jones

Sergeant Jones was attached to the Military Barracks in Brisbane, keeping order in the fledgling town, which usually meant dealing with insolent convict servants. Four years later, he was sent to New Zealand, as recorded by the Courier:

DOMESTIC INTELLIGENCE. THE BARRACK SERGEANT. — Mr. Jones, who has been for many years Barrack Sergeant in Brisbane, has received the appointment, at Wellington, New Zealand, vacant by the death of the late Barrack Sergeant Lovell, from injuries received during the earthquake in that afflicted town. Mr. Jones is one of the oldest residents in Brisbane; and we hope that the change in his situation will be—as we believe it is intended to be—a change for the better. Sergeant W. Little, late of the 80th Regiment is appointed Barrack Sergeant at Brisbane and will arrive by the next steamer.

Travelling to an earthquake-damaged post was thought to be a change for the better. Says a lot about Brisbane in 1848.

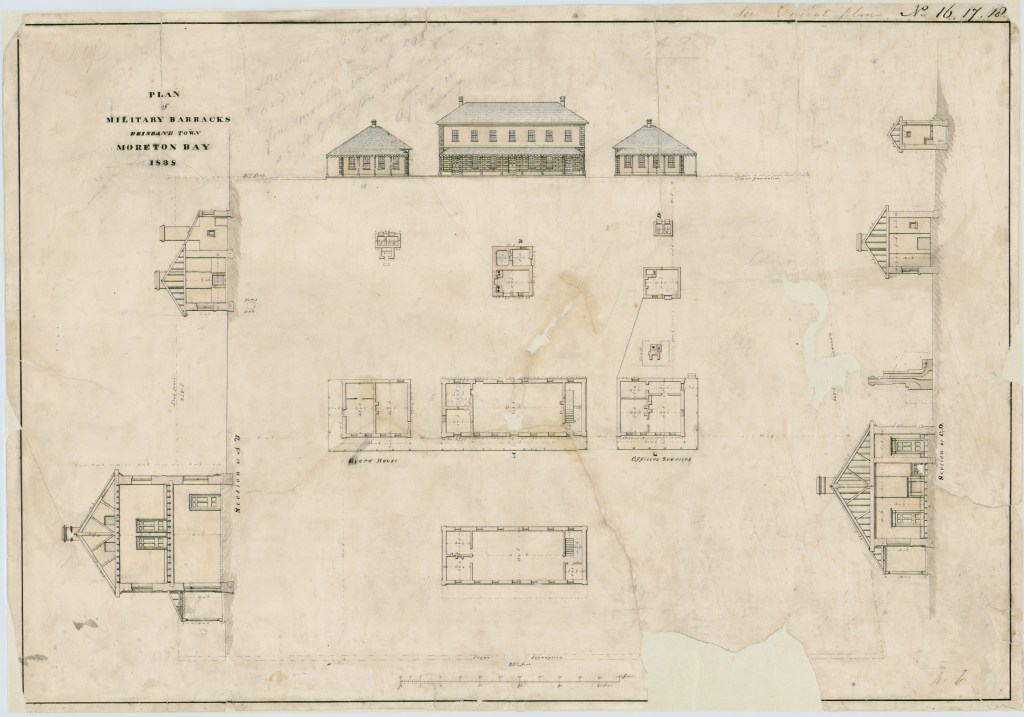

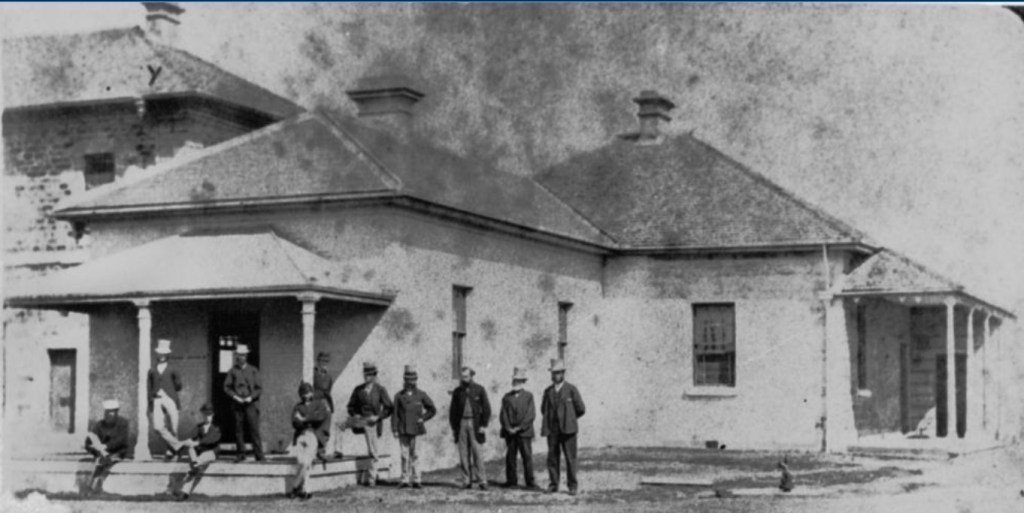

35. Soldiers’ Barracks

Plan of Military Barracks, 1838

Archer family at Military Barracks, 1870

Military Barracks, 1873

The Military Barracks housed the English soldiers who oversaw the settlement at Moreton Bay from 1824. The best view of them is probably as the background to the Archer family’s slightly bizarre photo above (why are the women sitting on the ground?). It was in this building that the “infernal vagabond of a woman,” Marcella Brown, snuck some spirits in to a (very) friendly soldier, earning herself a spell in solitary on bread and water.

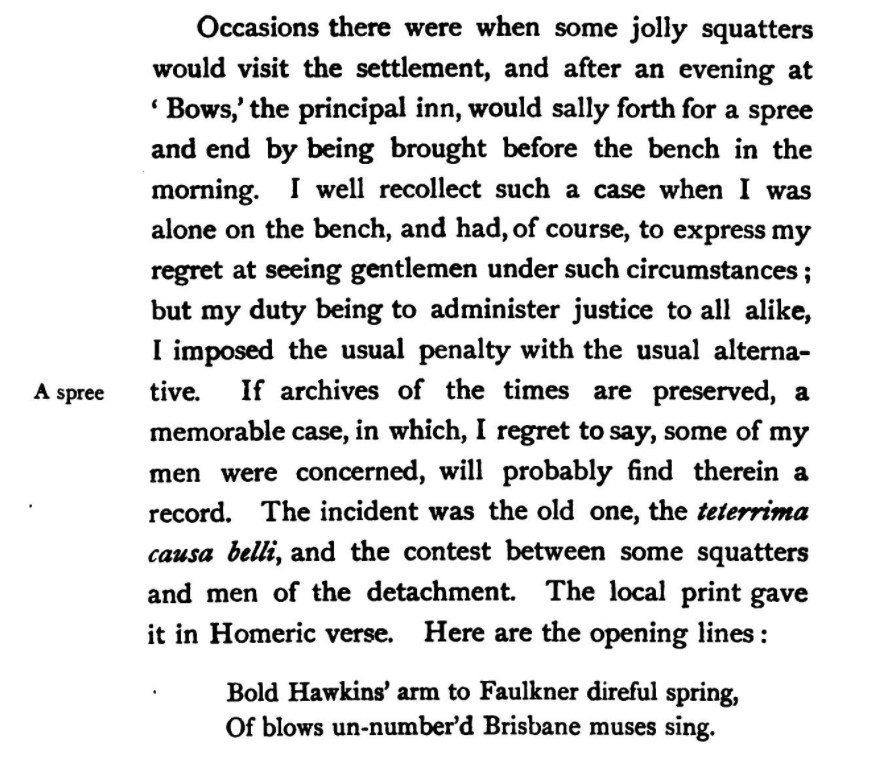

36. Officer de Winton

George Jean de Winton was a member of the 99th Regiment and came to Brisbane in command as Lieutenant of a detachment of that Regiment in 1843, at the age of only 20. He must have been a talented young officer, because by the time of his arrival, he had already served at Windsor, Newcastle, Port Macquarie and Tasmania. He was the first European to land and set up camp on the mainland at Gladstone, and, although greeted with some hostility by the local indigenous people, gained their trust. Largely by not employing traditional European methods of treating indigenous people – guns.

It was after the Gladstone journey that de Winton went to Brisbane. Lt de Winton made a point of visiting the Darling Downs, and districts closer to Brisbane Town, and on the basis of his journeying, became convinced that the region could be a new focus for British emigration. He wrote to newspapers and to friends, promoting the possibilities of Moreton Bay.

On 6 November 1847 at Brisbane, Rev Gregor conducted the marriage of George de Winton, Esq to Fanny, the youngest daughter of Thomas White Melville Winder, Esq. The following year, de Winton led a detachment of the 99th to Norfolk Island, where he remained on and off until being invalided off the Island in 1853.

George de Winton returned to England, much restored to health, no doubt by virtue of not being at the Norfolk Island penal colony any longer, and worked at a recruiting depot before seeing service in the Crimean War. After that war, he served on numerous boards and committees, and became involved in publishing, including his “Soldiering Fifty Years Ago: Australia in the ‘Forties,” which is a rollicking read.

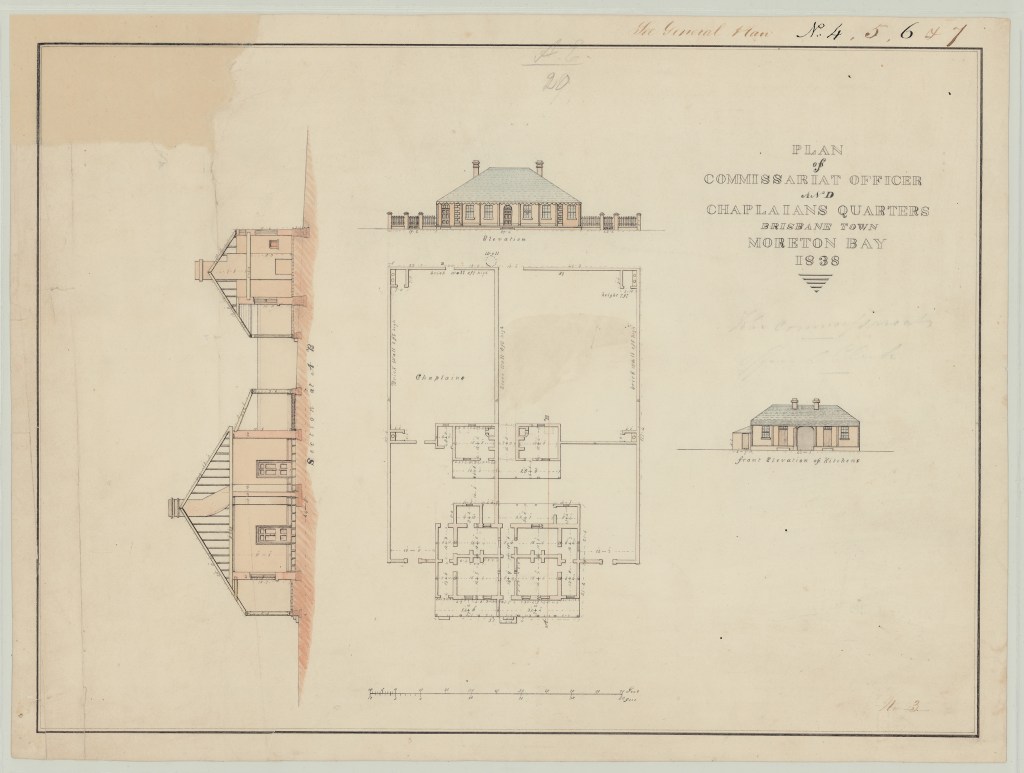

37. Commission Stores

The Commissariat Store, used to hold stock and stores for the Colony prior to distribution, is still standing in William Street.

It was built by convict labour in 1828-9, to some fairly exacting specifications. The walls were two feet thick, and the door was secured by iron bars. These measures were designed to prevent forced entry, presumably by starving convicts, but were only used for the purpose of repelling hordes during the Brisbane Riots of 1866.

The grey gum and tallow wood for the floors were sawn by the convicts, and secured with hand-made nails. Through numerous floods and centuries of use, the floorboards have remained true.

Commissariat Plans, 1838

Commissariat Store today

38. Queen’s Wharf

Queen’s Wharf was the landing point for the stocks and stores of the Commissariat Office in Brisbane. The precinct is now undergoing a redevelopment. Following the demolition of the more recent office buildings, William Street for a brief time looked exactly as it had one hundred years ago, with the Commissariat Store dominating the low-rise street front.

Queen’s Wharf in the distant past

Queen’s Wharf in the near future

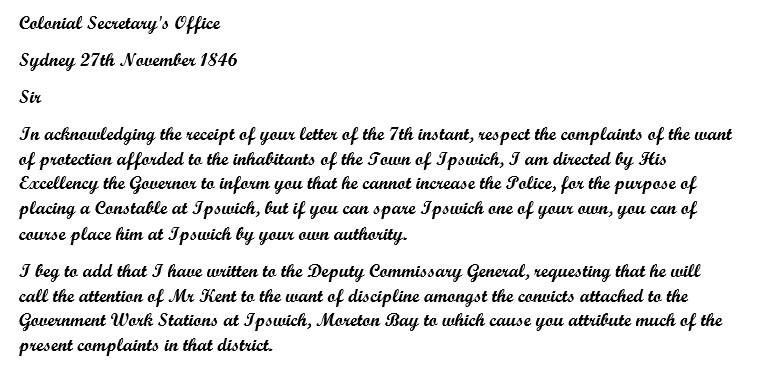

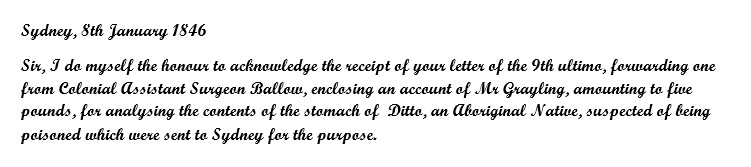

39. Captain Wickham’s office

I have written about Captain Wickham’s tenure at Moreton Bay before, and his decision to purchase of Newstead House, rather than reside in the unrepaired Commandant’s Cottage in Brisbane Town. He had an Office in town, at which he dealt with the many problems of Moreton Bay. Not least of his troubles, was the reluctance of his administrative masters in Sydney to afford any funds for the proper running of the settlement.

Wickham must have dreaded the arrival of the steamers from Sydney, bearing ever more officious letters from the Office of the Colonial Secretary. To give an idea of the myriad administrative problems facing Wickham, here are some extracts of the letters he received (no doubt handled professionally, responded to, and filed away properly; rather than torn to shreds or thrown at the wall, which would have been understandable).

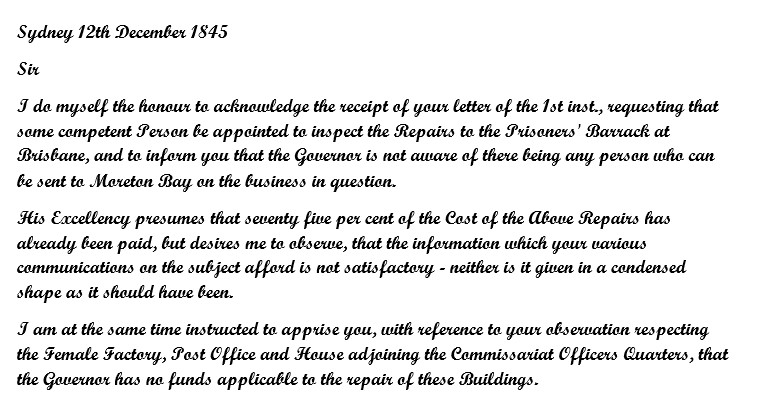

40. Commissioner T. Kent

John Kent (1809-1862) was Assistant Commissioner General for the military stationed at Brisbane.

In the 1840s, John Kent was a man who had the little world of Moreton Bay at his feet. He was, as Tom Dowse said, “in sole charge of the stock and stations the property of the Government at the settlement of Moreton Bay.” He was in his early 30s, and had married Margery Ballow in Brisbane on 21 June 1842, just as the settlement was receiving its first free inhabitants.

With Margery, he had seven children, although two did not survive infancy. Their first child, Cordelia, died on the same day she was born in 1843. The next daughter, Emily, was born a year later, followed by Keith in 1845, Frederick in 1848 (he did not survive infancy), Mary Ellen in 1849 and Douglas Vaux in 1850.

ACG Kent had the esteem and friendship of the many old pioneers of Brisbane Town, but he did rub some people the wrong way – a Mr Wiggings and Dr Dorsey in particular.

The Moreton Bay Courier described it as a “fracas in high life,” reporting on an assault case against Wiggings for slapping John Kent in the face. This occurred after Kent had told Wiggings’ servant that his master was a blackguard. Dr Dorsey imposed a one pound fine, and made some comments from the Bench that Mr Kent did not appreciate.

The very same issue of the Courier featured a very high-handed letter to the Editor from ACG Kent himself, to Mr Dorsey:

SIR-I avail myself of the columns of the Courier, to reply to your remarks, addressed to me from the Bench at Ipswich, on Wednesday last, (after a conviction in a case of assault, in which I was complainant), to the effect that my conduct had been improper in sending communications through servants, and that in all cases of dispute between gentlemen, they should be made personally.

I beg to protest against the applicability of the remarks to the case. Had such opinions emanated from the Bench through the chairman, they would have been unwarranted and extra judicial, proceeding from an individual Magistrate, without reference to his colleagues appeared personal and offensive.

I doubt if they were approved by any auditor in the Court-that they were sanctioned or countenanced by the majority on the Bench, I deny.

The circumstances of our relative position – that we were intimate, and have ceased to be so, -should have suggested to you the indelicacy of an exhibition of ought like private feeling, while acting in magisterial capacity.

I confess myself no less surprised at the advice, than at the source from whence it proceeded: and while fully admitting the value of your precepts, on prudential grounds alone, I would beg to suggest that they would acquire additional force if illustrated by example. Should circumstances ever place me in a similar position with respect to you, I shall follow your directions implicitly.

I am, Sir,

Your obedient servant,

JOHN KENT.

Brisbane, 5th November 1847.

Ouch.

John Kent Left Moreton Bay for England, cooling his heels briefly before taking up a position as Commissary General in the West Indies, then at the Cape of Good Hope. After another trip to England, and taking his pension, he decided that a Steam Sawmill venture at Kangaroo Point would be a nice little earner. He had the reputation in the colony, and hadn’t he pretty much run the place years earlier? Unfortunately, success in the public service does not automatically equate to success in business, and John Kent lost everything.

Kent turned to journalism, and edited the North Australian for several years, but was unable to resist meddling in politics, and getting involved in heated quarrels as he did so.

Government beckoned again, and he became a Police Magistrate at Maryborough, and his tenure was turbulent for all concerned. After that, a position as Crown Lands Commissioner for the district of Mitchell seemed to be the answer to his professional worries. Unfortunately, he became entangled in an acrimonious dispute with his administrative masters about costs and equipment, and never took up the appointment, remaining stubbornly at home in Maryborough. All of the goodwill from his ACG days at Moreton Bay had been used up, and he knew it.

In December 1862, John Kent was 53 years old and was becoming a concern to his friends and family. The zeal that had taken his career around the globe had gone, and he saw no prospects ahead. Mrs Kent was so concerned that she took to hiding his razors. At Christmas, Kent went to visit some friends who had just arrived by steamer, who found him noticeably quiet and despondent.

After spending the warm sub-tropical Christmas evening on the verandah with his family, taking in the evening air, he left the verandah quietly. The family remained, assuming that he had gone into the house to read, but found no trace of him when they went inside. Uneasy, they set about searching, and found him in the garden, with his throat cut. He had died almost immediately.

He was a man of astonishing memory, and possessed of vast stores of information, although, perhaps, of not much use to the owner of an acute and vigorous intellect, he might, if born under a luckier star, have filled a more conspicuous position in the eyes of the world with honour and dignity, but fate had decided otherwise. With less talent, less honesty, less independence of spirit, less contempt for parvenus and snobs, he might have been a more successful and happier, if not a better man.

Obituary, The Courier, Brisbane.

41. Commissioner’s Garden

The Commissioner’s Garden differed from the Government Garden, in that it was more of a kitchen garden, with (although I can find no mention) I imagine, some few flowering or decorative plants. In the survey of 1838, when plans were drawn, the only mention of the garden contains descriptions of the 3- slab fence (“very much decayed”).

42. Captain Coley

Richard James Coley born in England in 1797, and followed his father into the Merchant Navy, becoming Captain Richard Coley. Coley married Mary Goggs in 1835, and emigrated to Tasmania in the same year, setting up a farm. He was not wildly successful at this venture, and after some family connections had begun working on farming in Tasmania. In October 1842, he travelled to Moreton Bay, ahead of his family, to lay the foundations of a merchant business.

In April 1843 Coley made his first land purchase on George St, a little further up George St than shown in the Gerler Map, which places his residence near or at the old Commandant Cottage. This house, along with Fraser’s and Petrie’s was “said to be the first private residence in Brisbane,” depending on which old timer was doing the recollecting. (It was known as Captain Coley’s Cottage, and was still there at the beginning of the 20th century.) r his civic interests. Real estate may have been more lucrative than trading – in 1844 he bought land at Kangaroo Point, and made a huge profit when he sold it in 1853. This allowed him to buy more lots in North Brisbane.

Coley made a living as a merchant, but became better known in Brisbane Town for his civic interests. He became a member of the committee of the Moreton Bay Benevolent Society, then served as a juror in the first sittings of the Circuit Court in 1850.

Fair trading and civic-mindedness began to pay off. In April 1850 appointed the first Lloyd’s Agent for the district of Moreton Bay, then in November he a Director of the Bank of New South Wales. Other appointments of note were to the Queensland Steam Navigation Board, and the Queensland Pilot Board. These were largely honorary, and Coley kept trading well into the 1850s.

The appointment that meant the most was that of the inaugural Sergeant-at-Arms of the Queensland Parliament in 1861. An ancient role in the Westminster system of government, the Sergeant-at-Arms is responsible for maintaining order in the public gallery, as well as the house itself. Unruly persons can be escorted out by the Sergeant, and it’s a wonder anyone is left in the building at all.

Captain Coley enjoyed a few years in the role, before his gout became so painful that he had to miss a sitting of Parliament. He described the pain to his friends as nigh unbearable, and it just kept getting worse. On September16, 1864, Coley was at his house, speaking with his nephew; nothing was apparently amiss, but on leaving his nephew, he went to a store-room at the back of his house and took his own life with a pistol.

As agent for Lloyd’s, Captain Coley’s word in matters connected with our shipping interests was law, his extensive practical knowledge of the duties of a shipmaster, and his probity of character, commanding universal respect. In fact, previous to separation Captain Coley was considered in these respects one of our leading men

The Queensland Times

43. Government Gardens

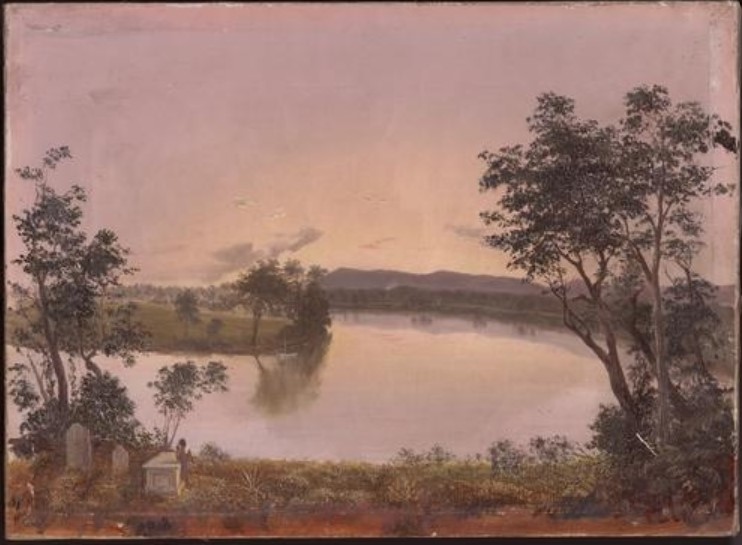

In 1829, explorer Alan Cunningham noted that the Government Gardener had about 14 acres of vegetables under cultivation in what is now the Botanical Gardens. The vegetables included peas, cabbages, pumpkins, hams, sweet potato and arrowroot.

Botanical Gardens 1868

Botanical Gardens and Curator’s Cottage, 1873

Botanical Gardens, damage to Curator’s Cottage, 1893 floods

Botanical Gardens, 1895

Botanical Gardens today.

In the 1840s, Tomas Roper recalled that the government gardens had become common grazing ground for people who kept horses, cows and goats. “There were a few stunted lime trees, guavas etc that the cattle had not completely destroyed.”

The photographs above show the gradual beautification of the area. In 1868, the grounds are mostly bare, and the lily pond is fenced in. By 1873, palm trees are better established, there is seating and a cottage for Mr Hill, the curator. By 1895, the gardens, in a hand-tinted photograph, have assumed the lush, sub-tropical beauty they have today.

44. Father Hanley (the only priest)

Rev. Father James Hanly was the only Roman Catholic priest in Brisbane in 1844, and the parish grew under his stewardship from worshipping in an annex to St Stephen’s Church, which opened in 1850. He attended to the births, marriages and deaths of the Roman Catholic community in the settlement, as well as ministering to condemned prisoners and trying to help the indigenous people of Brisbane. He found time, in 1847, to bless the union of James (Duramboi) Davis, and the first of his two rather fiery wives, Ann Shea.

Rev. Hanly appears in the accounts of two incidents where Europeans overreacted to the presence of indigenous people – the alleged shooting at York’s Hollow in 1846 and the woes of Mr Vicarrie, the Catholic missionary at Dunwich.

On the night of York’s Hollow, Rev. Hanly was visiting a friend when news of the injuries sustained by Kitty, a young indigenous woman, was brought to him. He hastened to see Kitty and asked her people if she could be taken to the Hospital, but they refused. (Kitty was variously reported as having been shot by the Police, dying in childbirth or being fatally injured by a waddie.)

Several months later, Mr Vicarrie, serving the Dunwich station as missionary, sought to be removed from the position, and to be afforded official protection by Captain Wickham, the Police Magistrate. According to a witness named McLachlan, he wrote to Wickham, and enclosed his letter in one to Rev. Hanly, with instructions for it to be delivered. The letter to Wickham was not delivered, and when the Courier got wind of it, they wrote that Rev. Hanly had suppressed the letter, leaving Vicarrie in danger.

Rev. Hanly contacted the paper, and advised that Mr McLachlan had given an incorrect account, and that the outrages committed by the indigenous people at Dunwich were greatly exaggerated.

From the accounts of what occurred at Dunwich, that may be true. The indigenous people borrowed Mr Vicarrie’s boat without permission, and some of the melons from Vicarrie’s garden were stolen. When Vicarrie caught the thief, they wrestled each other for the melons, and McLachlan claimed to have fired a blank cartridge to warn the indigenous man away. Apparently after that the indigenous people had taken to insulting Vicarrie daily. No harm came to him.

In 1850, Hanly had the unhappy, and seemingly unsuccessful, task of providing spiritual comfort to Patrick Fitzgerald, one of the two men hanged for murder at Brisbane Gaol. He remained by Fitzgerald’s side, praying with and for him, until the executioner arrived.

In 1852, on the death of Richard Jones Esq, or “Old R Jones,” as Gerler described him, Rev Hanly showed some genuine inter-denominational discretion by holding his service an hour earlier to allow his parishioners time to get to Richard Jones’s Anglican funeral.

In December 1854 and January 1851, Rev. Hanly once again attended to a condemned man. This time it was Dundalli, the indigenous warrior. Hanly had some trouble bringing the seriousness of Dundalli’s situation to him, the man apparently feeling that he could and would be sent to Sydney rather than being hung. Dundalli was not interested in what Rev. Hanly was telling him, but the priest carried on with his duty.

In August 1857, this unhappy duty fell again to Rev. Hanly. In this case, it was William Teagle, and Rev. Hanly was at last able to supply a great deal of comfort to the man. Rev. Hanly visited constantly, and his presence, right to the very end, was shown to comfort Teagle.

Later that month, Rev. Hanly was transferred to Patrick’s Plains (present-day Singleton) in New South Wales to minister the mission there. Hanly’s parishioners were deeply moved at the departure of the man who had been their priest for such a long time. Rev. Dean Rigny was appointed to take over in Brisbane

45. Saw Pits

Saw pits were designed for sawing large logs into more manageable sizes. Several men would work there – the log was positioned over the pit, and sawyers would work from above and below. It was here that the massive timber floors for the Commissariat Store began to take shape.

46. Queen Street

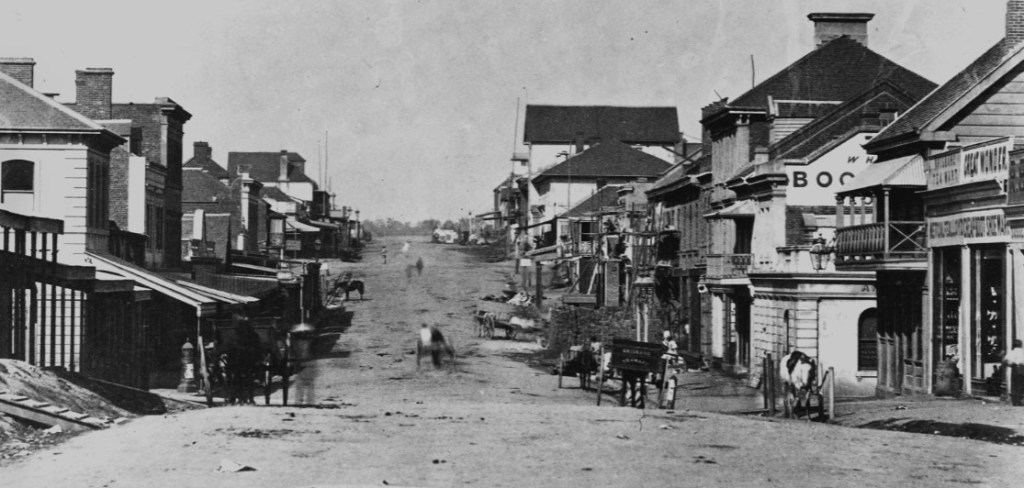

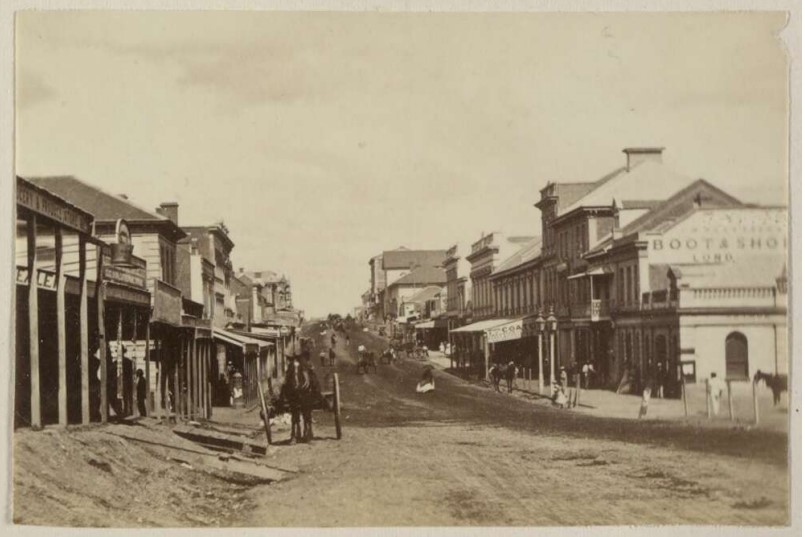

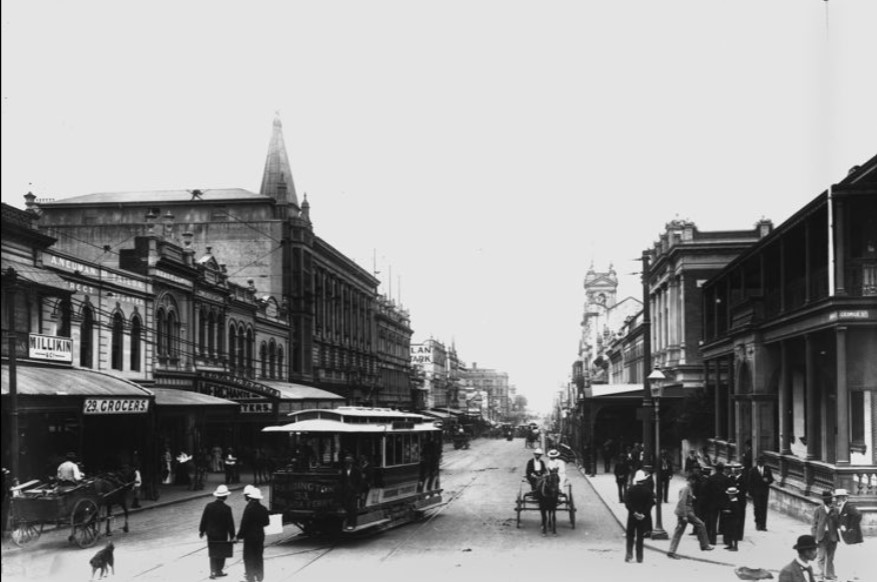

At the intersection of Edward with Queen Street was the beginning of Queen Street proper. But very few who are traveling Queen Street of today would have the slightest conception of what it was in the Forties. Then there were no friendly gas jets streaming forth to lighten the path of the luckless pedestrian – nothing more than a few oil lamps from the various little pubs by law compelled.

Thomas Roper, A Walk Through Old Brisbane

Queen Street, 1864

Queen Street, 1870

Queen St 1873 looking east

Queen Street, 1879, looking south

Queen Street, 1880

Queen Street, 1893, during floods

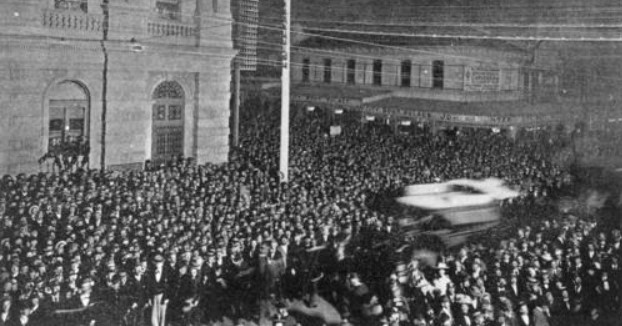

Queen Street, 1899, crowds waiting for Federation Referendum results

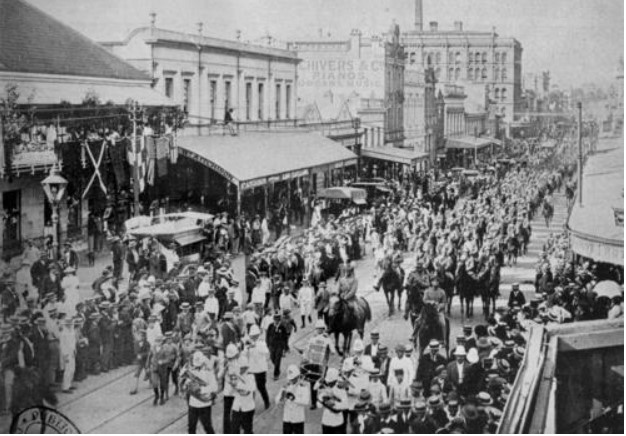

Queen Street, 1900, parade of troops (Boer War)

Queen Street, 1900, from George Street.

There were no asphalt pavements, no Macadamised streets. Water worn ruts were allowed to travel where fancy guided them, with here and there an old stump of a tree to entrap the unguarded wanderer. I remember meeting an old friend of the Samaritan type with his horse and dray drawing a load of stones to fill in a few of the deepest ruts around the corner of Messer’s Grimes and Petty. This was the only attempt I saw at repairing streets.

Thomas Roper

47. The Boat House and Boatman’s House

48. The First Tombstone (two graves)

This would appear, from the location, to be the graves of soldiers’ children on North Quay. (see entry no. 17 – the Burial Ground).

That concludes our ramble through the buildings and citizens of Brisbane in 1844, as drawn by Gerler in his map. I was struck by the contrast in the fortunes of the people on the map. The broken men, Sheppard and John Kent, ending their lives. The long, distinguished and quite publicly uneventful life of William Pickering, and the respected Sergeant at Arms, driven by intense pain to end his life.

Such wonderful stories….

LikeLike