Mr Wimble publicly horsewhipped Mr Draper, editor of the Cairns Chronicle, on Christmas night, owing to some personal remarks published in the Chronicle reflecting on Mr Wimble’s private character. Police Court proceedings will be taken against Mr Wimble. [i]

Public horsewhipping was a peculiarly 19th century method of dealing with a private grievance. It was more appealing than the often inconveniently fatal duel at dawn as a conflict management tool. An aggrieved gentleman could ride into a town, seek out the gentleman who had offended him and lay into him with a whip. Criminal charges might ensue, but at least one was spared the cost of a funeral. It was a decidedly male response to insult, although in February 1856, Lola Montez publicly horsewhipped the editor of the Ballarat Times for accusing her of immorality.

What had Mr Draper done to incur the wrath of Mr Wimble?

The Cairns Chronicle

The Christmas combatants were both local newspaper editors. Mr Wimble edited the Cairns Post, a (relatively) old, established paper in the steamy north. Mr Draper was new to town, and edited the upstart Chronicle, a journal much less prone to tiresome practices like fact-checking and journalistic ethics.

The Chronicle, after a quiet start, became the rabid tabloid of the North, and even before Mr Draper took over in May 1886, had weathered several rather colourful civil and criminal proceedings.

The Editors

Archibald Meston ventures north, edits in between crocodile-killing

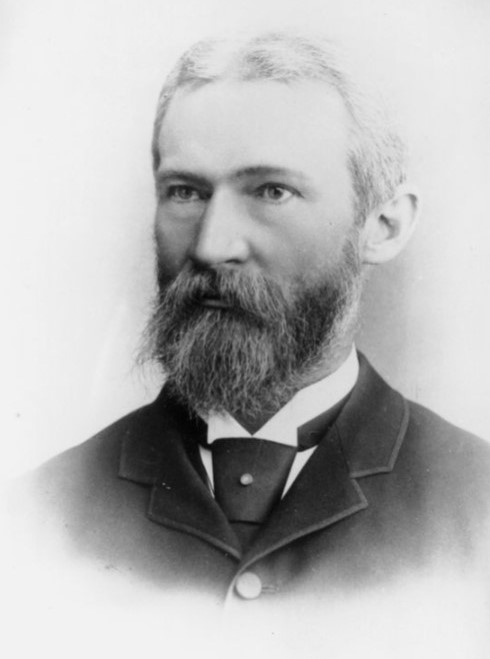

In February 1885, 34-year-old Archibald Meston, already a national celebrity, was asked to edit the Cairns Chronicle by the board of directors. Meston had been a farmer, sugar plantation manager, editor of the Ipswich Observer and the Toowoomba Chronicle, and a Member of the Legislative Assembly of Queensland, in the newly-established seat of Rosewood.

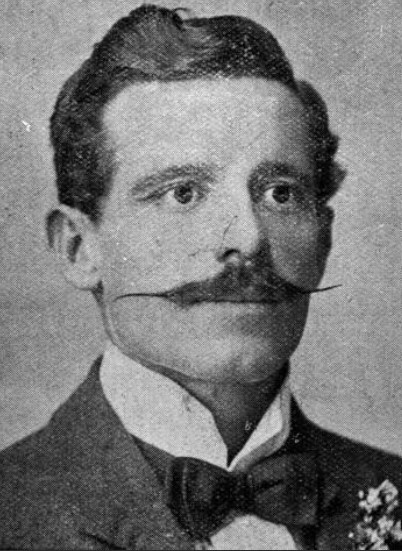

Archibald Meston, at the time he decided to go North.

Meston was a self-appointed expert in the ways of Queensland’s indigenous people, in the “noble savage” vein. Although he probably felt genuinely sympathetic to aboriginal people, his career as a lecturer and expert on same had more to do with PT Barnum than Charles Darwin (see the “Wild Australia Show”).

Leaving parliament after a bit of a financial scandal in 1882, Meston travelled north, chronicling at length his success in killing an inordinate number of crocodiles,[ii] editing the Townsville Herald, the Cairns Post, and even spending a few months in the driver’s seat of the Chronicle in 1885.

He left the paper over a salary dispute and was still in the process of trying to recover the money when the next editor, a Mr Piggott, decided it was high time to set about insulting people.

Mr Piggott insults Mr Knight and baits a magistrate

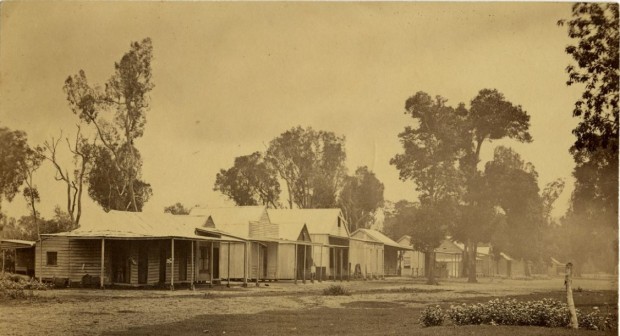

Cairns in 1884

Mr Piggott set to work with a will. He reported on a man kicking a dog outside the courthouse[iii], encouraged police action on a “hook-nosed loafer” who threw a bathmat at an old man[iv], and set about pouring scorn on Mr Wimble “the little whippersnapper round the corner.”[v]

Having dealt with dog-kickers, loafers and editors, Piggott decided to taunt the judiciary. He reported with undisguised glee that a solicitor, Mr Milford, had inadvertently referred to Judge Neal as “Your Worship,” rather than “Your Honour.” Judge Neal corrected the solicitor immediately, but Piggott couldn’t help calling it “a slip of the tongue and no gentleman would have noticed it.[vi]“

The Police Magistrate, Mr HM Chester, JP, was next. Piggott irked the Magistrate by failing to take notes or read the depositions at an inquest but managed to publish a denunciation of the written findings in the next column. When a further inquest was called in the matter, Magistrate Chester ordered Piggott out of the courtroom, and it was open season on Mr Chester from that moment.

“There are none who sympathise with him, except two or three good-for-nothing insignificant cads whose unhallowed carcasses would poison a 40-acre paddock if used as manure or would poison all the alligators in the Barron.[vii]“

The battle of the Police Magistrate wore on, but it was a combination of Archibald Meston’s pocket and a travelling photographer that ended Mr Piggott’s tenure as editor of the Chronicle.

In early May 1886, the Chronicle was reporting, with apparent glee, that they had a new staff member named “Brown, the bailiff.” He had been sent to recover the wages awarded to “that Barron-brained gentleman of alligator fame, Archibald Meston.[viii]“

At the same time, Mr Piggott decided to have a bit of fun at the expense of one Mr Onslow Knight, a travelling photographer. Piggott informed the Chronicle’s readers that a Chinese man named Tim Tee had told him that Knight was the son of another Chinese man, named “On Low.”[ix]

Mr Onslow Knight did not see the humour in this and took Mr Piggott and the Chronicle to the Circuit Court for libel. Knight won £350, plus costs.

By 22 May 1886, the directors of the Chronicle, totting up the cost of the Meston and Knight judgments, not to mention the repute of their publication, dispensed with Mr Piggott’s services, and decided to put the paper in the hands of Mr Edwin Charles Mollett Draper, brother of one of the directors, Captain Alexander Frederick John Draper.

“The new man will, doubtless, be expected not to run the paper into another Onslow Knight case,” opined the Queensland Figaro[x].

Sure.

Mr Draper insults Mr Chester, Mr McNamara, Mr Wimble and Others

Edwin Draper was a member of a prominent family in Williamstown, Victoria. As a schoolboy, he excelled in debate and elocution.

But we should certainly wrong Mr. Ulbrick and his pupils, if we did not specially notice the elocutionary part of the entertainment. The Banishment of Catiline fairly took the people by surprise, and bouquets of flowers were thrown to the heroes, Masters Felix Clauson and Edwin Draper, by ladies in the hall. Fifteen boys took part in the Debate and here also showers of bouquets honoured the best speakers, Masters Clausen, Ulbrick, Draper, Fowler and Usher.

Williamstown Chronicle, Saturday 26 December 1874.

When not having bouquets hurled at him by local matrons, he “was ever foremost in organising amateur dramatic and other entertainments, playing the principal characters himself.[xi]”

After sinking a small provincial paper and working as a travelling life insurance salesman in Victoria, Edwin Charles Mollett Draper (nicknamed “Hoppy” by his family) followed his brother Alexander Frederick John Draper (AJ) to the Deep North, and was appointed to edit the Cairns Chronicle, a promotion made less surprising by the fact that AJ Draper was one of the directors of the paper.

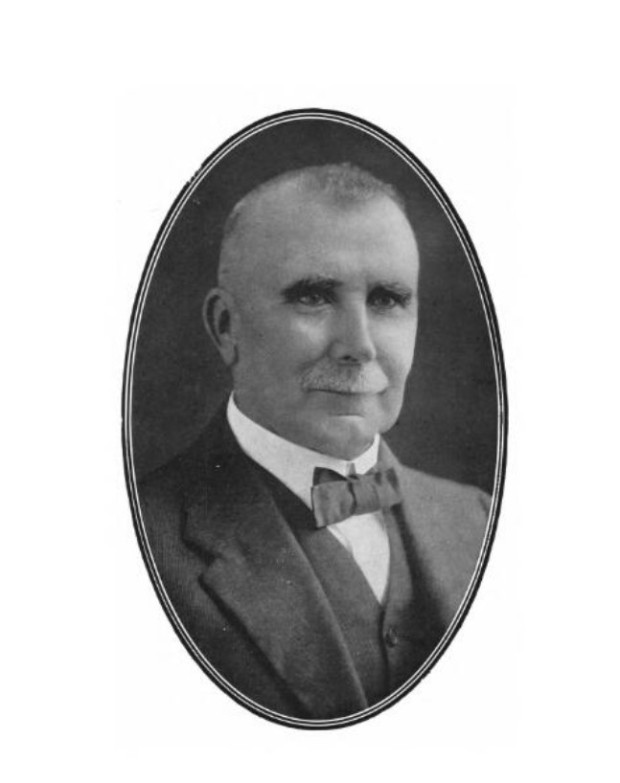

The young and strong-willed AJ Draper had already made the North his own, involving himself in newspaper publishing, sugar production, auctioneering, exploration, politics, the Bench, and the volunteer militia. Edwin was a fervent supporter of his buccaneering brother and was given a very long leash at the Chronicle.

The Drapers were passionate Separationists – they sought another Colony or State in the north of Queensland, an idea that is still being kicked around (without great enthusiasm) today. They supported the former Premier, Sir Thomas McIlwraith, and anyone who supported the incumbent, Sir Samuel Griffith (i.e., Mr Wimble) was anathema to the Drapers.

Rival businessmen, particularly auctioneers and those in the booming sugar industry, were fair game. The Drapers opposed a development named New Cairns, and the New Cairns Times, published by John (JHJ) MacNamara. Mr Wimble and the Cairns Post naturally attracted their ire, along with the continued presence of Magistrate Chester at Cairns.

Sir Samuel Griffith couldn’t get out of Cairns fast enough after his official reception.

Edwin Draper started out in cheerful style, reporting a near-riot caused by a beer cask of disputed ownership, and then the glorious official reception for the Hon SW Griffith, the expenditure for which had vastly exceeded receipts from ticket sales.[xii] Griffith, pausing briefly on his way to the first boat out of town, gave a brief interview to Draper, describing the grand gala as “the rowdiest and most disgraceful affair he had ever been invited to attend.[xiii]” The Hon Mr Griffith was fortunate not have been an attendee at the stolen beer cask rumpus.

Mr Macnamara, displeased at being depicted in Hell, goes to court

Draper first set his sights on a rival of his brother; an auctioneer and publisher named John HJ MacNamara. Unpleasant comments were printed about MacNamara as early as May when Mr Piggott found it necessary to leave town. After months of harassment, Mr MacNamara took Draper and the Chronicle to Court for criminal libel over comments published in November 1886. By the time the matters reached court in December, Draper was involved in a full-scale war with Police Magistrate Chester and had just gone five rounds with a sugar planter.

The first libel charge was brought over this:

“OH BUT”

“That we know that in the eyes of the world it is a sulphur and brimstone matter to point out an oversight of the Supreme Beings. However, we’ll risk it. That we think Providence might have exercised a little more ingenuity when he mapped out his great Egyptian plague programme.

That instead of the plague of lice with which he afflicted the erring Egyptians he should have planted a MacNamara amongst them.

That if he had tried this plague first and given them three months of him, divil another one would have been wanted. That the nuisances of frogs, darkness, hail, &c., &c., would have been as nothing compared to such an infliction.[xiv]“

The second count of libel was based on this paragraph:

“It was a morning in the infernal regions, and many unfortunates were grouped around the fires waiting for the daily agony to begin. They were beguiling the time re-counting the various misdeeds done while on earth which had led to their condemnation. One had wrecked a savings’ bank, another had stolen from widows and orphans, and a third had betrayed a dear friend. The whole catalogue of deeds done and duties undone which had brought woe to others was recited, and sins off every hue were represented in that unhappy company. Finally one miserable victim (naming the said J. M. J. MacNamara) said: ‘Comrades, each one of you thinks himself to have been very bad, but I (meaning the said J. H. J. MacNamara) am undoubtedly the worst of the lot. l am the auctioneer who sold New Cairns.’ A thrill of horror ran through the group, and they drew away from this offender. Just then the signal for the day’s business sounded, and a muscular demon seized the conscience-stricken land salesman. High above all the din rose the howls of the victim (meaning the said J. H. J. MacNamara) as they pitched him (meaning the said J. H. J. MacNamara) into that part of the furnace where flames glowed at the whitest heat.[xv]“

Just in case anyone was in any doubt, that’s JHJ MacNamara he was talking about, the auctioneer.

The Libel Hearing and Duelling Justices

On December 12, 1886, a panel of eight men – seven Justices of the Peace and the Police Magistrate – sat to hold a committal hearing on the charges against ECM Draper. Because the detested Magistrate Chester was sitting, one Alexander Frederick John Draper joined him on the Bench. For balance, presumably.

The committal heard evidence from one of the other directors of the Chronicle, a compositor, and a bookseller, as well as MacNamara himself. The evidence showed that Mr Draper alone had written the offending words. The Bench was split on whether the alleged libels were sufficient to warrant a trial at the next Townsville Assizes. Unsurprisingly, Alexander Draper led the movement to dismiss, and Police Magistrate Chester moved to commit. Magistrate Chester won the day, and, as the Brisbane Courier reported, “Mr AJ Draper, JP, created the most disgraceful scene by openly abusing the police-magistrate in court, and said that he ought to be hounded out of town.” Restrained public comment clearly ran in the family.

Mr Bates, insulted, clobbers Mr Draper

Mr RW Bates ran the Pyramid Sugar Plantation and had become wealthy and influential through vigorous use of “Kanaka[xvi]” labour, and whose interests rivalled those of one AJ Draper. Edwin Draper obligingly called Bates an ass in an “on dit” in the Chronicle.

Mr Bates stormed first into the letters page of the Cairns Post to pour vitriol on Draper and the Chronicle:

“When a man mistakes vulgarity for wit, abuse for satire, impertinent personalities for just criticism, and has as much regard for the truth as Ananias, and as much respect for the amenities of life as a hyena, it is pretty evident that Providence never intended him for an editor.”[xvii]

Bates was much better at insult comedy than Draper, and he followed his letter up with a visit to Cairns to sort Mr Draper out. On November 24, 1886, Bates fought five rounds with Draper at the rear of Paton’s Hotel and won. He had the honour of being the first Cairns notable to lay hands on Mr Draper.

After the Christmas Horsewhipping.

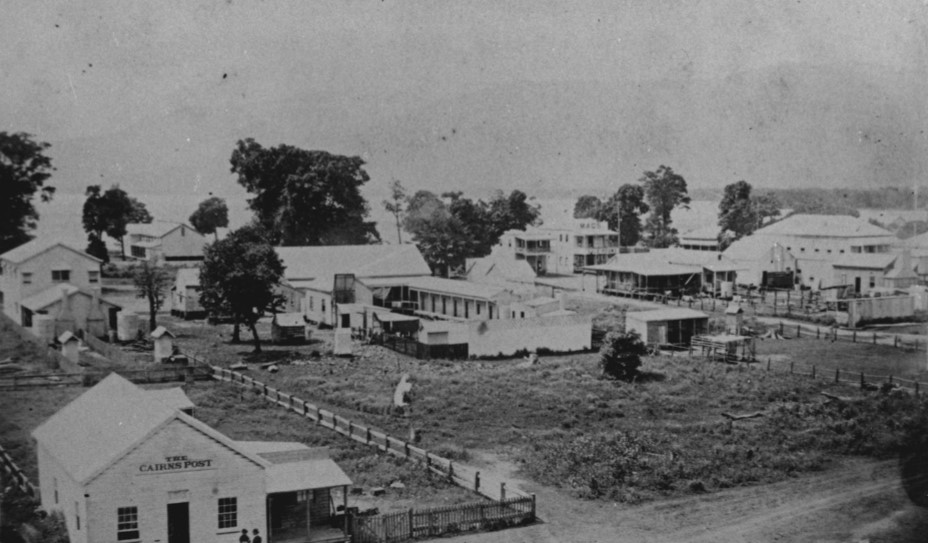

The Cairns Police Station, 1896. It saw a lot of Draper and his antagonists over the years.

Despite the enormous personal satisfaction of horsewhipping Mr Draper, Mr Wimble knew that he had committed criminal assault, and quietly pleaded guilty at the first opportunity (January 5, 1887). He was fined £3, with £1, 7s. costs.

Edwin Draper had little time to celebrate Wimble’s conviction, because a day later, a fed-up Magistrate Chester went to Court over a libellous “prayer” published in the Chronicle. The initial complaint was dismissed – to Edwin Draper’s premature jubilation – on a technicality. Mr Chester had not included the libellous words in his information. The complaint was re-filed, and once again, Draper was committed for trial for criminal libel. In February 1887, it was reported that the Attorney-General found no true bill against Draper.[xviii]

The systematic abuse of Magistrate Chester ended when the poor man was transferred to Cloncurry, and appointed Police Magistrate and Gold Mining Warden in that place. [xix]

Edwin Draper may have felt that he was bullet-proof, a state of affairs confirmed when he was widely reported to have drowned when crossing Freshwater Creek in March 1887. A Mr Shaw, secretary to the Hospital, saw Draper wade across, and when the editor did not make the return journey, his family and the police were engaged in a distressing search for his body.

“They looked everywhere, they shouted out his name, but in vain; then a happy idea struck one of the party to attempt to cross the creek, and ride on to the railway camp to inquire, and there the corpse of our editor was found enjoying his cigar in company with friends, and his pockets full of notes about the railway line!”[xx]

The Chronicle had a great deal of fun with that, publishing “A Protest from the Corpse.” The Week wondered when the horsewhips would come out next, and they did not have long to wait.

In June 1887, the new editor of the Cairns Post saw Edwin Draper in Abbot Street one Saturday night and decided to settle ancient journalistic and political differences with punches. This time, the fight went for nine rounds, “both rolling in the sand”[xxi] and Draper was crowned the winner.

Three public fights, multiple libel cases and a brush with drowning in only one year. Perhaps not coincidentally, it was announced that a former Post editor, Dr Myers, would manage and edit the Chronicle henceforth.

After the Chronicle

The Chronicle quietly folded not long after the colourful Draper era, and AJ Draper diversified his media holdings, finding employment for his turbulent brother at the Cairns Post and the Morning Post in the 1890s. As AJ Draper’s biographer noted, “Whatever “Hoppy’s” abilities as a writer were, whatever the strength of his argument and the penetrating power of his invective, he was not regarded as responsible in business matters.”[xxii]

In 1898, Edwin was forced to give up work on the Morning Post, suffering what the Williamstown Chronicle described as a “serious illness.” In 1901, he died, aged 40 “after a life of exceptional vitality.” He had been, despite his verve and editorial cheek, a martyr to rheumatism for some time.

His family were still litigating his will as late as 1903.[xxiii] AJ Draper, naturally, was the executor. Another Draper brother and other business associates wanted to pursue the estate as creditors of ECM Draper, only to find that AJ Draper had transferred the newspaper holdings to his wife, Georgina.

The Cairns Morning Post building after the 1906 Cyclone.

AJ Draper survived, had successes and reversals, and died on a business trip to Brisbane on 21 March 1928. He left an estate of £49,989[xxiv] – a stark contrast to his late brother, who left the world a rather duller place, and with an estate valued at under £1,938.00.

[i] Morning Bulletin, Rockhampton, Tue 28 December 1886.

[ii] Brisbane Courier, Wed 20 February 1884, page 3.

[iii] Reported in the Mackay Mercury and South Kennedy Advertiser Wed 24 Feb 1886.

[iv] Reported in Queensland Figaro and Punch, Sat 13 Mar 1886.

[v] Reported in Queensland Figaro and Punch, Sat 20 Mar 1886.

[vi] Reported in the Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton), Wed 14 April 1886.

[vii] Reported in Queensland Figaro and Punch, Sat 8 May 1886.

[viii] Reported in Warwick Argus, Tue 18 May 1886.

[ix] The Brisbane Courier, Tue 11 May 1886.

[x] Queensland Figaro and Punch, Sat 22 May 1886.

[xi] Williamstown Chronicle, Sat 23 April 1898.

[xii] Cairns Chronicle Sat 15th May 1886.

[xiii] Reported in the Logan Witness (Beenleigh) Sat 29 May 1886.

[xiv] Cairns Post, Thurs 16 December 1886.

[xv] Cairns Post, Thurs 16 December 1886.

[xvi] “Kanaka” labour in this context refers to the use of South Sea Islanders on plantations in Queensland in the 19th century. These workers were variously kidnapped, threatened or tricked into working in the colony. Their experiences ranged from outright slavery to poorly remunerated physical labour with the promise of a return journey on completion. Those who did not get the return passage were subjected to wholesale deportation in 1901 under the White Australia policy.

[xvii] Cairns Post, Thurs 4 November 1886.

[xviii] Morning Bulletin, Rockhampton, Thu 24 Feb 1887.

[xix] Darling Downs Gazette, Wed 4 May 1887

[xx] The Week, Brisbane, Sat 26 Mar 1887.

[xxi] Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser, Tue 14 Jun 1887.

[xxii] “The Life of A.J. Draper” compiled and Published by “THE CAIRNS POST”(For Private Circulation), Cairns, The Cairns Post Ltd, 1931.

[xxiii]North Queensland Register, Mon 27 July 1903.

[xxiv] Catherine May, ‘Draper, Alexander Frederick John (1863–1928)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.