In April 1840, the Colonial Secretary, by command of the Governor, did himself the honour to acquaint the Commandant at Moreton Bay that the schooner John had been engaged by the Commissariat to bring 15 prisoners to work for that department in Brisbane. The men had been transported earlier that year – 13 in the Layton and two in the Westbrook. Their names were listed in the correspondence as:

By the Layton:

- Vengear

- Ernest Cyprian

- Noel La Fortune

- Jean Cora

- Pierre Louis Etienne

- L’Esperance

- Victor

- Eugene Doucette

- Pierre Louis Raoul

- Cactane

- Celestine

- Cassim.

By the Westbrook:

- Pierre Richard

- Arniot Mauguy.

Looking at this list, Commandant Gorman would have been quick to come to the conclusion that this group of prisoners weren’t the usual collection of English or Irish waistcoat thieves. Still, they were the Commissariat’s problem, not his. He had his hands full with Assistant Surveyors Dixon and Stapylton.[1]

The prisoners were a group of men tried at the September and December 1839 Assizes at Port Louis, Mauritius. They were sentenced to transportation and were initially sent to Van Diemen’s Land to be assigned work. Van Diemen’s Land, the colony closest to the Antarctic, was a shock to the systems of the men from tropical Mauritius, and arrangements were made to get them back to the mainland. This was an unusual concession from the Governor. The cold weather must have had a terrible impact on the health of the men.

The group waited in Sydney for a few weeks before being sent to subtropical Moreton Bay in the John.

The Mauritian convicts had already lived through torrid times in their homeland. Centuries of French rule ended with a battle between French and English forces at Port Louis in 1810. The English took over running the colony and had done away with the slavery that had supported the Dutch and French administrations since the 1500s. Several of the convicts were old enough to remember the battle that took place in Port Louis, and the change to English rule. Most of the men were Mauritian born, but two were originally from Mozambique and one from Calcutta.

The fortunes of the Mauritius convicts in their new lives in Australia were varied. Some left Moreton Bay when the Commissariat no longer needed them, others became very ill, and a few survived to become community founders. All except one received Certificates of Freedom within a few years of arrival.

The Convicts

We know a little about the convicts from Mauritius through their convict records. Their names vary from document to document, as Englishmen tried to spell the unfamiliar handles. For their part, the convicts were all unable to read or write – at least in English (the only language that would have mattered to the Colonial administrators).

CAETANE (also CACTANE, CATANE, COCTANE)

Caetane was born in Mozambique around 1795. He was about 45 years of age and had fathered four children – two boys and two girls – but was accounted for as single on transportation. Presumably he was a widower or a de facto husband. He was a fisherman, who was convicted of arson on 28 September 1839 at Port Louis and received 7 years’ imprisonment. He had no previous convictions.

Although small in stature – just 5 feet tall – Caetane would have been an arresting figure. He had tattoos on his temples and nose, and extensive ink on his chest. His hair, complexion and eyes were noted as black.[2]

On 14 May 1844, he was awarded a Ticket of Leave no 44/1333 as “Catane,” and was permitted to remain in the district of Moreton Bay.

Due to his unusual name, and its variants, it is difficult to trace Caetane through Births, Death and Marriages in New South Wales and Queensland. He is also hard to find in newspapers.

CASSIN (also CASSIM)

Cassim was born circa 1820 in Calcutta India, making him 20 years old when transported for seven years for the crime of theft. His religion was listed as “Musselman,” an old-fashioned term for those who followed Islam, particularly black Muslims. He worked as house servant in Mauritius and may have been part of the “coolie” labour introduced to that country when slavery was abolished in the 1830s.

Cassim was also a small-made man, just over 5 feet in height. He had a dark copper complexion, with some pockmarks and black hair and chestnut eyes. His right ear was pierced. Three months after arriving, Cassim was hospitalised at Moreton Bay from 24 August to 7 September 1840. The disease was not specified in the hospital register.[3] In November 1843, he was admitted to hospital again, this time with rheumatism.[4]

Cassim was granted a Ticket of Leave much earlier than the other Mauritius convicts. On 20th December 1843, Cassim was granted Ticket of Leave No 43/2988, “Per the Government Minute on a Memorial by Mary Taylor, the wife of the Prisoner Cassim.”[5]

Aside from his wife’s testimony, Cassim was given an early Ticket of Leave because of his public spirit. In 1841, the towns of Ipswich and Brisbane were flooded. Ipswich was cut off, and the settlers there were left without food. Cassim, who was then in service at Limestone, alternately walked and swam to Brisbane to let the authorities know of the situation upstream. Legend had it that he washed up at Petrie Bight, to the astonishment of the locals.[6]

“Cassam” was employed by the Government as an interpreter for “coolie” labourers in 1846,[7] and the following year joined the indigenous people of Amity Point in assisting the recovery of survivors, victims and property in the wreck of the Sovereign. Unsurprisingly, he was granted a certificate of freedom in January 1848.

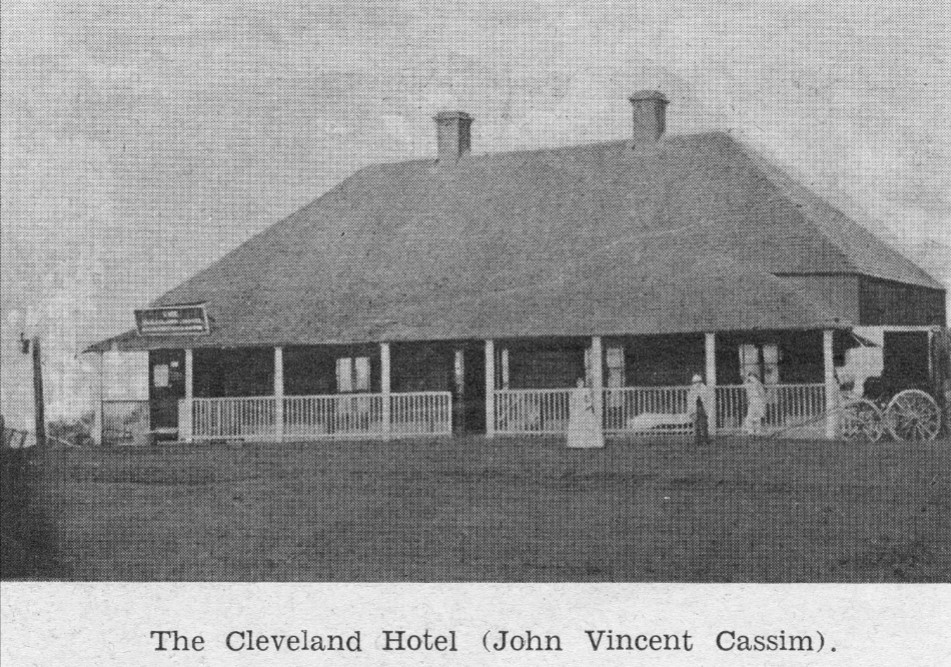

In the 1850s, John and Mary Cassim set up a boarding house at Kangaroo Point, and then at Cleveland. John Cassim’s experience as a house servant in Mauritius paid off, and he was an attentive and deferential host in his establishments.

“First and foremost amongst the hotels is the Cleveland Hotel, kept by Cassim—the venerable Cassim, who is as much associated by name with Cleveland, as was Adam with the Garden of Eden. As long as we remember Cleveland, Cassim stands before us. He arrived many years ago, and was in the service of the pioneers of Cleveland—the Bigge’s—and faithfully served them until he became a Boniface and held a license for the Brighton Hotel, built by Mr. Bigge. There Cassim entertained visitors for some years, until he built his present hotel, and his reputation for quiet civility, respectful demeanour, a good table, and obliging manners, has rendered him a favourite and his house a comfortable abode.”[8]

The Cassims enjoyed tremendous success until Mary died in 1861, aged only 45. John battled on alone before marrying Anne Rafter in 1868. Anne proved to be as astute as her husband at the hospitality trade, and the Cassim family and name became synonymous with Cleveland.

John Cassim died in February 1884 and was buried – at his request – at Amity Point, the site of the Sovereign shipwreck nearly 40 years earlier.[9]

“Another old landmark shifted, and a watermark too. John Vincey Cassim has had to let go his moorings at last, tenacious though he was. Who, amongst the frequenters of the old, old hotel at Cleveland, that antediluvian watering place and retreat for sick sinners, did not know old “Cassim.” Twenty years ago, and goodness knows how long before, he was “old Cassim.” A notable man, sirs. Dark in skin, even as El Mahdi, he was careful to tell you that he came of L’Isle de France people. A little active fellow he must have been before the deluge which wafted him to Cleveland. Grit, every bit of him; with a keen eye for “the main chance,” and accumulative propensities strong, yet honest, and, on occasion, liberal. Full of strange yarns about the time—and before and since—the old Sovereign was lost; all in all, he was Cleveland’s most notable personage, not excepting the Fogartys, Taylors, and Winships. He cut the painter at last, a few nights ago, but the steamer that took him over to his final resting place had plenty to do, even with the help of the clergy, to bring him to anchor. Made five distinct tries for it before it could be done. Well in was the old man. Cash about £3000, farm about same, hotel £1500, and a widow.”[10]

CÉLESTIN (ALSO CELESTIEN)

Cèlestin arrived in Moreton Bay aged 20, with a life sentence for Highway Robbery hanging over him. He was short, very dark-skinned, and had lost his third and little fingers on his left hand. Shortly after arriving, he spent nearly two months in Moreton Bay Hospital being treated for syphilis.

His condition improved enough for him to be a very useful man about the settlement. In 1843 and 1844, he was constantly in reports to the Colonial Secretary for his hard work:

1843

43/0456: With the Border Police, employed as a bullock driver’s mate (April-June 1843)

43/0459: Employed as a splitter and fencer.

43/08025: With the Border Police, putting up buildings and fences (July-September 1843). With Border Police, cultivating for forage (October – December 1843)

1844

44/03049: With the Border Police as a Mounted Trooper (January – March 1844)

44/05565: With the Border Police as a Mounted Trooper (April – June 1844)

44/06593: Assisting Dr Simpson with the recovery of a body

45/05176: With Border Police as a Mounted Trooper (July – September 1844)

45/0327: With Border Police as a Mounted Trooper (October – December 1844).

In October 1845, as his fellow Mauritian convicts were obtaining Tickets of Leave and Certificates of Freedom, Cèlestin absconded from Moreton Bay. (Although a Celestin was awarded a Ticket of Leave in Tasmania in 1846, it was not the same individual. This Celestin had been tried and transported in 1841, two years after Celestin of the Layton.) The Moreton Bay Cèlestin was never heard from again.

“Celestine, Layton, 1840, 25, Mauritius, labourer, 5 feet 1£ inches, black comp., black woolly hair, black eyes, large featured, nose short and broad, lost third and little finger of left band, marks from leeches on left side, from Government employ, Moreton Bay, since 9th October 1845.”[11]

JEAN COCO

Jean Coco was another 20-year-old Mauritian, who was convicted at the Port Louis Assizes in 1839. He was also a house servant who had been convicted of theft. Apart from a physical description – copper coloured complexion with smallpox scars, “hair black and woolly,” and ears pierced – we have very little information about him.

As Jean Cocqueaux, he spent ten days in Moreton Bay Hospital with syphilis in 1843, he received a Ticket of Leave for Moreton Bay in 1844[12], and a Certificate of Freedom in 1847[13].

ERNEST CYPRIEN

Ernest Cyprien, a cook born circa 1820 in Mauritius, was given a 10-year sentence for theft at Port Louis. He must have been ill on arrival at Moreton Bay because he was admitted to hospital on 10 May 1840 for an unspecified disease. Fortunately, he only needed four days to recover.

He was granted a Ticket of Leave on 28 May 1847,[14] and was allowed to remain at Moreton Bay, and, recorded as “Ernest Cyprio,” died on 11 May 1854.[15]

EUGENE DOUCETTE (also EUGENE or JOHN LUCETTE)

Eugene Doucette was only 18 when he was transported for theft in 1839. He was described as half-caste, with a pale copper complexion, and was taller than most of his shipmates and 5 feet 5 inches.

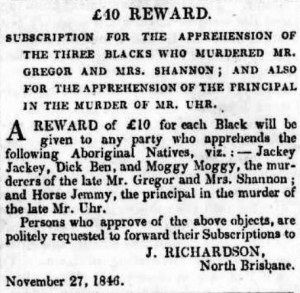

Eugene Doucette became a well-known figure about Moreton Bay and was involved in several of the major events of the fledgling settlement. He was a witness to the York’s Hollow shooting, involved in the violent arrest of one of the Shannon-Gregor murder suspects, and took part in the apprehension of the Norfolk Island convict pirates.

He worked for the Commissary until 1843[16] – he also spent a month in hospital that year with epilepsy – a disease that may have shortened his life, as treatment for that condition was rudimentary.

By 1847, Eugene Doucette had become close to the indigenous peoples of the Moreton Bay district. He learned to speak their languages – having mastered French as a child in Mauritius, then English. Few European settlers had bothered themselves to become fluent. Doucette also worked with, and at times lived with, the aborigines. He obtained his Certificate of Freedom that year.[17]

Doucette was working as an assigned servant to G.S. LeBreton in late 1846 when a series of affrays broke out between the European and indigenous population of Moreton Bay. The deaths of John Uhr in January 1846 and those of Mary Shannon and Andrew Gregor in October led to vigilantism by some European settlers. The York’s Hollow shooting stemmed from an attempt to capture Jackey Jackey, believed to be one of the killers.

Eugene Lucette examined, states -Two days after the attempt to capture Jackey Jackey, I went to the blacks’ camp to cut brooms. I asked the blacks where Bobby was. They told me he had gone to the Bunya Bunya, because he was frightened. I have not seen Bobby since the night in question.[18]

In June 1848, Doucette was involved in the arrest of Omilly, who had by that time been implicated in the Gregor-Shannon murders. Looking at the report of the inquest, it seems that Doucette was at the very least partly responsible for Omilly’s death in custody.

This is his evidence (I have removed the word “witness” and substituted “I” to make it clearer):

Eugene Lucette : On Friday morning last I was told by a black gin that one of the late Mr Gregor’s murderers was in the camp of the natives near the settlement. I gave information of the circumstance to the Police Magistrate, and with a party of constables proceeded on Saturday evening last to the blacks’ camp to apprehend him. A black named Stephy Cullen pointed out the deceased as being the man. I then went into the camp with Bobby Winter, an aboriginal native, who immediately on seeing Omilly, said that’s the fellow. Winter and I then laid hold of him; I put a rope round his neck and under his arm, for the purpose of securing him, as he was making violent efforts to escape. The constable then came up and put handcuffs round his ankles. A violent tumult ensued among the blacks; the friends of Omilly then tried to rescue him, and threw boomerangs and spears, one of which wounded a constable. The friendly blacks then laid hold of the rope, Omilly at the same time struggling hard to escape, and dragged him up the hill. I suppose that during the struggle Omilly’s arm must have slipped out of the rope, and that he must have been strangled while making violent efforts to escape. I did not know that he was dead until he arrived in Brisbane. No more violence was used than what was necessary to apprehend the deceased. [19]

At this enquiry, Eugene Doucette also acted as an interpreter for indigenous witnesses.

Eugene Doucette made his living as a fisherman, working with a crew of indigenous men. He also lived with the indigenous people – something that the colonial authorities could not or would not understand. In February 1850, he was enduring some hard times, and was convicted of vagrancy and sentenced to three months’ imprisonment in the newly opened Gaol in Queen Street. The Courier noted that under the Act, he might have been liable to two years’ imprisonment, and used his case as a warning to anyone who had “no settled place of abode.”[20]

In 1852, whilst fishing in the Bay, Doucette came across the former editor of the Courier, A.S. Lyons, who was in the throes of a strange adventure related to the desertion of some crew from an immigrant ship, Meridian. Lyons, who had taken to living a drifter’s life in the bay (but had of course not been arrested for vagrancy), encountered a group of men he suspected to be the deserters from the Meridian. The men had a boat with them, and Lyons, for reasons known only to himself, assisted them in navigating to Cleveland Point. A long series of misadventures followed, including an encounter with Eugene Doucette, who, at Lyons’ request, took the Meridien’s boat to town. Lyons, who had travelled as far south as the Tweed, and then back to the Bay, managed to end up stranded and starving on Peel Island before he was rescued. Lyons told his tale to his former newspaper, the Courier, to try to dispel gossip that he had assisted the deserters. It was so unbelievable that it had to be true. Possibly.[21]

Moreton Bay was an interesting place at that time. Not only could one encounter destitute former newspaper editors in possession of suspicious landing craft, but one could also encounter convict pirates from Norfolk Island.

In 1853, a group of nine prisoners at Norfolk Island conceived and carried out a desperate plan to escape their penal servitude, taking over a boat and heading out into the Pacific with no particular plan other than getting away. They fetched up at Stradbroke Island, fought amongst themselves, robbed the Harbour Master’s crew of everything from their boat to their clothes, then made off for the mainland. Enter Eugene Doucette.

“On Thursday a fisherman, named Eugene Lucette, arrived in Brisbane with the boat taken by the runaways from the Harbour Master’s men. He stated that he, with his boat’s crew of native blacks, had seen the runaways land and haul up their boat amongst the mangroves near the mouth of the river, on the south side, and afterwards go away into the interior of the country, and that early on the morning of Thursday he and his blacks went and seized the boat and brought her up the river.”[22]

Eugene Doucette popped up in the news again that year as an interpreter for two indigenous men who were charged with stealing at Pine Mountain.[23] That’s about as dramatic as the rest of Doucette’s life was, and he was probably grateful to be clear of shootings, strandings and pirates. He remained at Moreton Bay until his death in 1860.[24]

ETIENNE

Etienne was a 20 old shoemaker convicted of theft in 1839. The little known of him consists of his appearance, a hospital visit, and his release from convict bondage.

He was born in Mauritius in 1820, was Roman Catholic, and single. He stood 5 feet, 5 ¼ inches, had a copper complexion, and black hair and eyes. In 1844, he was treated at Moreton Bay Hospital for gonorrhoea.

On 13 February 1845, Etienne was given a Ticket of Leave.[25] He was permitted to remain in the district of Moreton Bay.

NOEL LAFORTUNE

Noel LaFortune had a trade as a silversmith and was convicted of stealing gold in 1839. He had an impressive collection of scars on his face and no previous convictions. He worked at Moreton Bay for three years before falling victim to febris intermittens[26] and requiring hospitalisation for two months in 1843.

He was granted his Ticket of Leave in 1845,[27] only to have it cancelled the following year for “being insane,” as the note on his cancelled ticket bluntly put it. Shortly afterwards, he appears in the Darlinghurst Gaol Description and Entry Book with no other details beyond his name.

At the time, there was no dedicated facility for mental illness in Moreton Bay, and, as his Ticket of Leave was cancelled, the only thing to do with him was to ship him back to Sydney, and let the authorities at the Gaol decide whether to send him to Tarban Creek or assign him some service.

THE Tickets of Leave of the undermentioned Prisoners of the Crown have been cancelled for the reasons stated opposite to their respective names.—

Noel La Fortune, Layton, being of unsound mind; Brisbane Bench.

J. M’LEAN. Prin. Sup. of Convicts’ Office, Sydney, 6th May 1846.[28]

Noel LaFortune survived another 30 years, passing away in the district of Parramatta on 29 November 1875.[29]

L’ESPERANCE

L’Esperance was a little older than most of the Layton convicts – 25 at the time of transportation – and he was a native of Mozambique. He had been a stableman and received 7 years’ imprisonment for stealing wood.

His records also do not disclose much beyond his appearance and progress through the convict system. He was taller than his ship-mates at 5 feet 6 inches, and dark-skinned, and sported considerable tattooing on his face. This would have startled his colonial masters.

In 1844, he received a Ticket of Leave to remain in the district of Moreton Bay, and his Certificate of Freedom in October 1851.[30] Where he went and what he did after that is not recorded.

PIERRE LOUIS

Pierre Louis was another 1820-born Mauritian shopman convicted of theft and sentenced to 7 years. There must have been a fair bit of it going around Port Charles’ young men that year. He suffered the usual unflattering and frankly racist description on the convict indents: “black complexion, black and woolly hair, black eyes, nose broad and flat, lips thick, scar left side of forehead, another outside left eye.”

In early 1844 Pierre Louis sought medical attention for a nasty case of catarrh, and also received his Ticket of Leave.[31] He was ordered to remain in the district of Moreton Bay.

In the early 1860s, a man named Louis Pierre was listed as a subscriber for the building of a School of Arts in Maryborough. I like to think it might possibly have been him. Pierre Louis passed away in August 1868.[32]

LAURENT MAINGARD

Laurent Maingard was a one of the more mature Layton convicts. He was born circa 1805, and would have had some childhood recollection of the conflict that expelled the French from his country in 1810. Maingard had lost the use of his right side “from a paralytic stroke” before transportation, and the hard physical labour expected of the men at Moreton Bay may have been unsuitable for him. By the time of his Ticket of Leave,[33] he was at the Port Macquarie settlement, and a Certificate of Freedom followed in 1846.

JEAN MARTIAL

Jean Martial was the oldest of the Layton convicts, aged 45 on arrival in Australia. He was a Baker from Mauritius who was convicted of theft with violence in July 1839. He had some prior criminal convictions, unlike his shipmates. And he would have towered over those shipmates at 5 feet 9 inches. His indents noted that he had begun to go grey. He also had quite a collection of burn marks and scars, possibly as a result of his work in kitchens.

Jean Martial was also sent to Port Macquarie. He had a minor skirmish with the law in 1847 – it appears to have been a breach of servitude agreement. It did not count to heavily against him, and he received his Certificate of Freedom[34] in June 1849, stipulating that he should remain at Port Macquarie.

PIERRE RICHARD

Pierre Richard (born 1803) came to Australia on the Westbrook, following conviction at the December Assizes at Port Louis. His offence was house robbery, and prior to going to gaol, he had been a house servant. In 1844, he joined his fellow Pierre (Louis) at the dispensary at Moreton Bay with a nasty case of catarrh. The following year, he received his Ticket of Leave,[35] stipulating residence at Moreton Bay. His behaviour had been noted on the Westbrook’s records as “bad.”

LOUIS PIERRE RAVUL (also LOUIS PIERRE RAOUL)

Louis Ravul, a copper-skinned man of average height, had been born circa 1803 in Mauritius. He worked as a house servant and plain cook before deciding to commit highway robbery in 1839. He was transported for seven years in the Layton, and eventually washed up in Brisbane, working for the Commissariat.

His time at Brisbane was relatively uneventful, apart from 10 days in Hospital in 1843 for a fever. He earned a Ticket of Leave in May 1844, and a Certificate of Freedom in December 1847.[36]

A Louis Raoul died in Brisbane in January 1887.[37]

ROMEO

The Colonial Secretary’s letter mentions two men who had been transported from Mauritius on the Westbrook. They were Pierre Richard and one “Arniot Mauguy.” The Westbrook only took two men from Mauritius – Richard and Romeo. It was Romeo who turned up in the schooner John with the other 14 convicts.

Romeo was at least 40 at the time and had been a cook before being convicted of house robbery and given 8 years’ transportation. He had fathered two children – one boy and one girl – but was listed as single at the time of his offence. His behaviour on board the Westbrook was noted as “bad.”

Romeo had two stays in Moreton Bay hospital – in July 1843 he suffered a contusion and was barely released before being readmitted with febris. The record of cases and treatment show him as “Romeo Juliet,” a romantic name for a man with an unromantic life.

Romeo was granted a Ticket of leave on August 8, 1844. He didn’t live to receive a Certificate of Freedom, dying on 11 June 1846.[38]

VENGEUR (Benedictum Vanzeur, Van Zo)

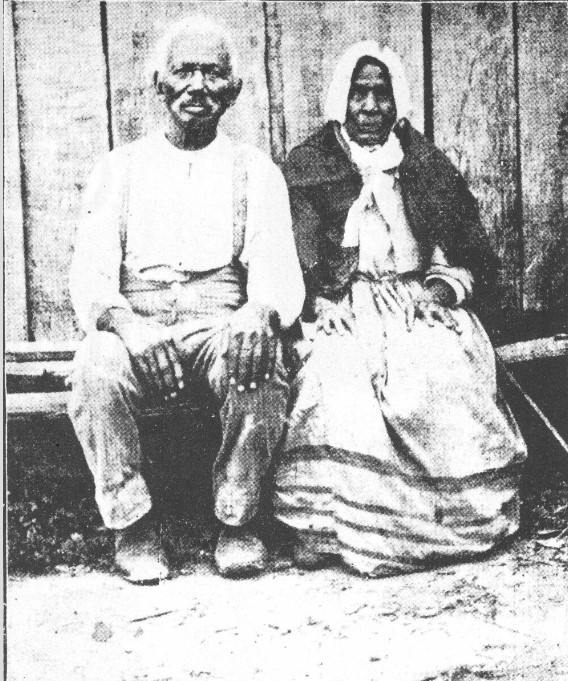

Benedictum and Marian Vanzeur pose for the Queensland Times’ camera.

The man described as “Vengeur” on the Colonial Secretary’s letter and his Layton indent became as well-known in Queensland as John Vincent Cassim. He’s the only Mauritian convict whose life story and photograph are well-documented, so it’s best to let Benedictum Vangeur or Vanzeur tell his tale in the Queensland Times[39]:

Benedict Vanzeur was born in the Isle of France (Mauritius), at Port Louis, eighty-two years ago—1813—and, on the 3rd of July 1839, was transported (along with fourteen others) to Australia, for ten-years’ imprisonment, for having received, as a present, a stolen waistcoat! As he himself very bitterly says, when speaking of his sentence, “I was ‘lagged’ out here to be branded as a convict because I accepted from one whom I thought a friend, a gift of a waistcoat! Yet that was justice! After leaving the land of his birth, Vanzeur was taken to Van Diemen’s land, where he stayed a couple of months, when he was taken on to Sydney (because it was too cold for them in the “tight little island”). They remained thirty-five days in Sydney, when he and thirteen of his mates were despatched to Moreton Bay, two of the life-sentenced convicts being left in New South Wales. Of course, Van Zo and his fellow prisoners were all coloured men.

After landing in what is now Brisbane (Chambers was the name of the captain of the vessel that, brought them over), Van Zo was at once started off to the Limestone settlement, via Cooper’s Plains, and placed under charge of Mr. George Thorn; the member for Fassifern’s father who was superintendent of the Ploughed Station, arriving there in May, 1840; so that he has been living in and around Ipswich for over fifty-five years.

Of the “founder and father of Ipswich,” he says that the late Mr. George Thorn was a fine fellow, and that there, were two little boys—George and Henry—when he and his ten black “chums” arrived here, but he laughingly remarked, ” Young Mr. George Thorn looks as old as me, now.” Van Zo worked for a time on the Ploughed Station, which, he says, when he went there, was a large area of corn and wheat, the quarters of the prisoners being a big slab shed, in which a very rough lot of customers were domiciled under the surveillance of soldiers.

The “station” occupied the site of the old Ipswich racecourse, now known as The Grange paddock. Verily, this particular portion of the surroundings of Ipswich has been the scene of many wonderful doings—first, it was the centre of what really was “the settlement” this side of Brisbane; then, during the latter part of the fifties until about the middle of the seventies, it was the headquarters of horse-racing in this colony those brilliant sporting times! Ah! alas, those racing days! Where are they? Let one climb that high chimneystack that marks the beginning of a gigantic effort to unearth coal at a depth of 1400 ft. and seek the spirits of that gay old jovial period!

Besides the corn and wheat fields at the Ploughed Station, there was a tobacco-plantation, which occupied the slope of the hill from what is—now known as Thorn-street—Mr. Superintendent Thorn living on the block of land where Mr. George Thorn now lives right to the edge of Devil’s Gully and the “curing”-shed was built on a site in East-street, on the land known as Gorry’s properties. Besides getting lime—the kiln in those far-off days being situated not a great distance from the residence of the superintendent, just about where the railway-line crosses a gully—attending to the growth of corn, wheat, and tobacco, there was also a flock of sheep to be attended to, and “shearing times” at the Ploughed Station are described by old Van Zo as having been very lively occasions. The sheep were generally kept on the north side, and “camped” on the bank of the river where the Woollen Factory is now erected. The sheep were washed in the Brisbane River (Kholo), and, after camping a night on Hungry Flat (Brassall), crossed the Bremer River at the Coal Falls (Lynch’s Crossing), the only crossing to Limestone in the early days.

Van Zo remembers Governor Gipps visiting the Ploughed Station in 1842, and the consternation there was, afterwards, when Limestone was proclaimed open to free settlement, at which time the name Limestone was changed to Ipswich. It may not be out of place here to quote from a letter written by the late Mr. Andrew Petrie in reference to the Brisbane and Bremer Rivers, in which he (Mr. Petrie) says:

“Previous to Sir George Gipps’s arrival here [Moreton Bay, from Sydney], I placed about fourteen beacons on the various rocks and shoals between Ipswich and Brisbane, and, after his arrival, I accompanied him from Ipswich to Brisbane, down the river, in a boat, and pointed out to his Excellency all the various obstructions to navigation. The worst was at the junction of the two rivers.”

Just so. Of course, Sir George came to Ipswich via Cooper’s Plains. All the river traffic from Ipswich to Brisbane was done by punts, the journey from the “head of navigation” to Brisbane occupying generally three and four days, and there are representatives of families in Ipswich at present who came up the river in punts. These were the only means of conveyance until the steamer Experiment ran from Brisbane to the “port of Ipswich” in June 1846.

Van Zo distinctly remembers Mr. Hugh Campbell’s father and family coming to Ipswich, and living first on a site on the other side of the One-mile Bridge, near the, water-hole known in those days as Black Neale’s hole. The Campbell family—all from Argylshire, Scotland, from thence to Scone, in New South Wales, where they resided nearly three years— arrived in Ipswich in June, 1842, and were among the very first free settlers in this town. The Moore family came shortly after, and from thence, following in the wake of the opening up of the Darling Downs by the Leslies and other squatters above and below the Range, commenced the ”building up” of Ipswich. But, regarding Van Zo:

Shortly after the settlement in Ipswich by the free people, a terrible murder was committed on the site of the Ploughed Station, a Miss Moore being the victim, who was a sister of Mr. Thomas Moore, now of South-street. It was supposed that the blacks committed the deed, and Van Zo succeeded in capturing and bringing to town the two black-fellows, Peter and Jacky-Jacky—notorious scoundrels, both of them–who were credited with having murdered the young girl, for which (principally the efforts of the late Archbishop Polding) Van Zo received his pardon, and he became a free man. He describes the blacks as being terribly treacherous in those days, and he himself had, on three different occasions, very narrow escapes, as the aboriginals did not “take” to his colour at all and, strange to say, the three natives (of different tribes) who tried to dispose of him was each a “king.” Van Zo was too wide awake for them.

At this period, he was following the occupations of shepherd and fencer. He was on Messrs. Ferreter and Uhr’s Bellevue Station , on the Brisbane River, at the time Mr. W. Uhr was killed by the blacks ; and he also remembers Baker being brought in after living so many years with the blacks. Mrs. Van Zo, his wife, is one of the batch of coolies brought over from Calcutta (India) by Mr. Gordon Sandeman, in 1848, for the purpose of opening a station on the Burnett, this, too, being about the period a batch of orphan boys was sent over from Sydney to Moreton Bay, to be distributed anywhere employment could be found for them.

In January, 1855, Marion Cowley was united in “holy wedlock” to Benedictum Vanzeur by the Rev. Father McGinty. Early in the sixties Van Zo ran a ferry across the Bremer, about opposite the Glide’s wharf, and, for years, after wards, lived on the Brisbane River. They are a thoroughly honest old couple. She is above seventy-six years of age. Advancing years have, however, left them in anything but good circumstances, but, owing to the kindness of residents and Ipswich people, the wolf is kept from their door. As an instance of genuine sympathy with the aged pair, an extract from a letter forwarded to Mr. Vanzeur will show that there are some really good-hearted people in our midst.

The property was originally purchased by Van Zo, who, however, felt the pinch of hard times, and their “old home” had to go; but the letter referred to states that “with the view of saving you a home for life, I now inform you that you and your wife are at liberty to occupy the same during your life. Thus, the new owner of the property. The above photograph was kindly taken by Mr. J. T. Barrett, son of Mr. P. Barrett, the well-known tanner, of Churchill.

VICTOR

Victor was the youngest of the Mauritian convicts – 15 years old when he boarded the Layton to be sent to Australia. Again, he was a house servant convicted of theft. It’s starting to look like the house servants of Port Louis got together and decided to become thieves.

Victor was a “slight made” teenager, who was of mixed race, giving him a “pale and copper coloured half-caste complexion.” He had marks from leeches on his stomach, the result of some fairly typical medical treatment of the time.

Victor was issued a Ticket of leave 14 May 1844[40], permitted to remain in the district of Moreton Bay. Tracing his movements afterwards is rendered difficult by his name – any search on “Victor” will call up thousands of references.

[1] Dixon had just sent a fetching young Irish convict named Marcella Brown to Sydney at his own expense. Marcella was in an interesting condition, and Dixon believed that Gorman had dallied with her. The feud brewing between Dixon and Gorman would reach the Colonial Secretary and His Excellency very shortly. Surveyor Stapylton had made complaints about just about every convict in the Survey Department, leading to a torrid few weeks on the Bench, as Gorman heard all of his cases. Stapylton would be murdered at Mt. Lindesay shortly afterwards.

[2] New South Wales, Australia, Convict Indents 1788-1842. Non-annotated printed indentures.

[3] Register of cases and treatment – Moreton Bay Hospital 06 August 1839 to 07 July 1842. Queensland State Archives Item ID 2897.

[4] Register of cases and treatment – Moreton Bay Hospital 13 July 1842 to 30 November 1843. Queensland State Archives Item ID 2901.

[5] New South Wales, Australia, Convict Pardons and Tickets of Leave, 1834-1859. Home Office: Settlers and Convicts, New South Wales and Tasmania; (The National Archives Microfilm Publication HO10, Pieces 31, 52-64); The National Archives of the UK (TNA), Kew, Surrey, England.

[6] Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Tuesday 26 February 1884, page 3

[7] Colonial Secretary Correspondence – Moreton Bay, CS 46/07357

[8] Week (Brisbane, Qld. : 1876 – 1934), Saturday 11 January 1879, page 15

[9] Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Tuesday 26 February 1884, page 3

[10] Queensland Figaro (Brisbane, Qld. : 1883 – 1885), Saturday 16 February 1884, page 18

[11] New South Wales Government Gazette (Sydney, NSW : 1832 – 1900), Friday 7 November 1845 (No.91), page 1258

[12] Ticket of Leave 44/1536 14 May 1844.

[13] Certificate of Freedom 47/615

[14] New South Wales, Australia, Ticket of Leave, 1810-1869, 28.05.1847

[15] Queensland Registry of Births Deaths and Marriages

[16] Colonial Secretary Correspondence: CS 43/00859

[17] Certificate of Freedom 47-615 dated 30 July 1847.

[18] Sydney Chronicle (NSW : 1846 – 1848), Wednesday 24 February 1847, page 4.

[19] Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1846 – 1861), Saturday 3 June 1848, page 2:

[20] Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1846 – 1861), Saturday 9 February 1850, page 2.

[21] The Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1846 – 1861) Sat 16 Oct 1852. Page 2

[22] Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser (NSW : 1843 – 1893), Saturday 28 May 1853, page 2

[23] The Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1846 – 1861) Sat 26 Nov 1853. Page 2.

[24] Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages Queensland 1860/B/495

[25] Ticket of Leave 45/389.

[26] Possibly malaria, sufferers experienced sudden spikes in temperature.

[27] Ticket of Leave 45/1514

[28] New South Wales Government Gazette (Sydney, NSW : 1832 – 1900), Friday 8 May 1846 (No. 37), page 580:

[29] New South Wales Registry of Births Deaths and Marriages 9090/1875

[30] 44/1538 and 51/120.

[31] 44/1539 May 1844

[32] QLD Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages: 1868/C/719.

[33] Ticket of Leave: 18 May 1844, permitted to remain in the district of Port Macquarie (on recommendation of the Windsor Bench.

[34] New South Wales, Australia, Certificates of Freedom, 1810-1814, 1827-1867. (NRS 12210) Butts of Certificates of Freedom. 1849. June.

[35] Ticket of leave: 11 January 1845. To reside at Moreton Bay.

[36] New South Wales, Australia, Certificates of Freedom, 1810-1814, 1827-1867, (NRS 12210) Butts of Certificates of Freedom, 1846, October. Australia, List of Convicts with Particulars, 1788-1842

List of Convicts with Particulars 1840 – 1842.

[37] Registration details: 1887/B/19580

[38] Registration details: 1854/BBU/411

[39] Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser (Qld. : 1861 – 1908), Thursday 15 August 1895, page 2

[40] Ticket of Leave 44/1544 14 May 1844.

Hi,

My name is Bevan Victor and I was given a link to your website recently. My wife and I think the history on Moreton Bay you have produced is fantastic and very well put together.

I am a descendant of one of the Mauritian convicts in your story. He is the youngest convict Victor and I am one of his Great Great Grandson’s. His name became John Victor and he married a young Irish lady Maria Langtree on the 12th of February 1850 in Brisbane. Your story matches everything that we had gathered about the Mauritian convicts over the last 10 years or so, of family research. It was so exciting to read it all again.

John Victor purchased land (Lot30) 44 acres in Enoggera, Brisbane in 1858. He & Maria had 11 children, 4 dying in infancy/childbirth. He was a farmer and later moved to Sneyd St Bowen Hills, near the Exhibition Grounds before his death in 1883. He was buried in Toowong Cemetary along with other members of the Victor Family as mentioned below.

John Victor the young convict from Mauritius was buried at Toowong Cemetery in 1883.

He is buried there, along with his eldest son, John Victor (2) aged 38, with John’’s (2) sons, James Edward Victor aged 26, Ramous Andrew Victor aged 28 years, also, infant sons William Herbert Victor and Lewis Vincent Victor. At the bottom of this headstone reference is also made to John Francis Victor the eldest son, who was buried at Rookwood Cemetery in Sydney aged 36. ( He is my Grandfather)

Thank you for a great read, we will keep looking for updates.

Kind Regards,

Bevan & Noelene Victor

Marburg

Qld

LikeLike

Dear Bevan and Noelene, thank you very much for this information – it’s wonderful to know that Victor established a family in Queensland. I had a lot of trouble searching for “Victor” alone and would never have discovered anything about him without your information. It’s amazing to think that a very young man sent to a strange country survived the conditions, learned the language and found his way in life. Thank you also for your very kind words about my blog. I apologise for not replying sooner – I was unwell for a while, but am back researching and typing now. Kind regards, Karen

LikeLike

Hi Karen,Thanks for your reply. I am so sorry I missed it until today. I was revisiting your website and saw your comments. Many thanks again for the work you have put into your research. Do you have my email address? If so,could you contact me as I may have more info on the Mauritians for you?

LikeLike

Hello,

I have just finished reading this article and i think you must have many cousins in Mauritius try this link https://www.cgmrgenealogie.org/actes/

With kind regards,

Dev Seelochan

LikeLike