Convict at Moreton Bay 1827-1833.

The Cordwainer’s stolen pillow-case.

In Hull Packet of 24 October 1809, Messrs Croudace and Stork proudly announced the opening of the Hull Coffee-Roasting Office. No longer would the flavour of Hull’s coffee be injured by London Traders’ careless stowage, or by moisture damage through carriage by sea. It would be the finest and freshest coffee a discerning Yorkshireman could ask for.

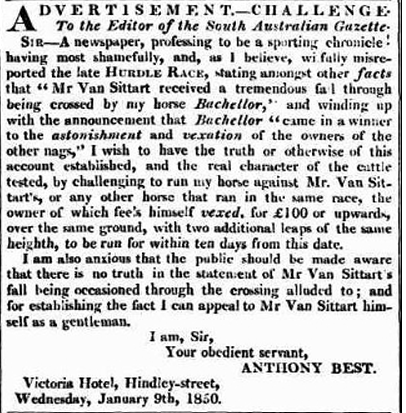

The Packet also reported on the East Riding Quarter Sessions, and the trial of Thomas Lawson, Anthony Best, Mary Ogle, Sarah Williams and Jane Lord charged with stealing property from one Adolphus Nordblad. Mr Nordblad had locked his house up, gone to London for a couple of weeks, and returned to find several of his cupboards had been broken open, and “property to a great value” was missing.

Some of the stolen property was apparently found at Best’s place – some pillowcases that had once been a cradle sheet. Mr Nordblad’s sister-in-law swore that she recognised the darning marks she had made on them.

Mr Smith, the Georgian predecessor to the prison snitch, deposed to a conversation that the three female defendants had while on remand: “Mary Ogle[i] had said they were to have “a crack” in a few days; afterwards, she said, “the crack was done” – they had “carried a parcel of screws to the Old King,” with which they had “dubbed the jigger.” The women said that some of the property was hid in a close behind the gaol.” Okay.

That must have been bad, whatever it meant, and the jury unhesitatingly found the defendants guilty. They were sentenced to transportation, except for Jane Lord, who was too old to manage a voyage to the other side of the globe in the name of correction.

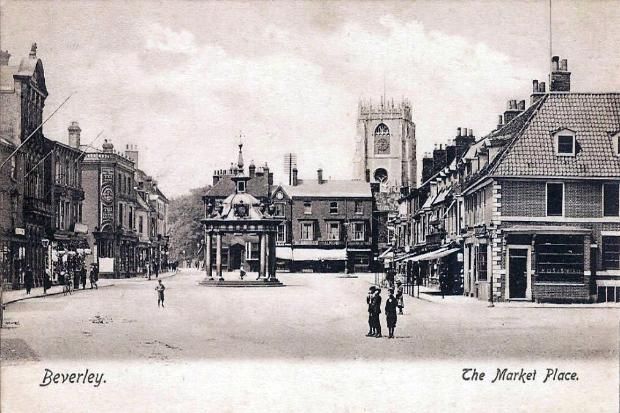

Thus began Anthony Best’s extraordinary career. He had been born in Beverley around 1772 (his age varies by about five years, according to who is recording it), and had married Margaret Bennington in 1800. He was the father of John (born 1801) and David (born 1807) and gave his occupation on the pollbooks as cordwainer.[ii] He had never gone far from that astonishingly picturesque town, and it seems a shame that a cradle-sheet made into two pillowcases was the cause of his permanent exile from it and from his young family. (Margaret and the young boys were in no position to make their own way out to New South Wales.) Anthony Best arrived in New South Wales by the Indian in 1810.

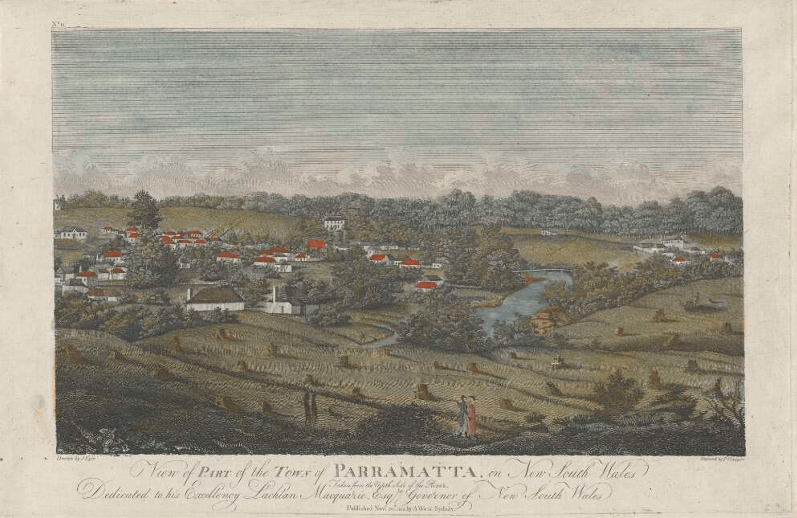

Early years in Parramatta.

In 1811, Anthony Best was a convict worker at Parramatta, and had accepted local resident John Blakefield’s offer of a room at his house until he could afford somewhere to live. John Blakefield had a wife, Hannah (nee Clothier[iii]), a former convict whom he had married in 1806. The Blakefields had two sons – Charles and Thomas. Young Thomas passed away in 1811, and that seems to have been the time when Hannah Blakefield became close to her new lodger, whose own wife and sons were a world away.

The Reverend Samuel Marsden, giving evidence in a court case in 1823, described to an eager press gallery his horror at what happened next:

“Many months, or weeks, did not elapse before the rights of hospitality were cruelly invaded by Best. The wife of his charitable host was seduced; and poor Blakefield, overcome with genuine grief, shortly after died of a broken heart!

“Best, and the miserable woman, soon left the town of Parramatta for that of Windsor, where it was hoped they might be partially screened from glaring guilt. The Reverend Gentleman said, that in his Clerical duty, he had repeatedly upbraided Best with his conduct towards poor Blakefield.“

It is true that a child named Samuel Best was born on 14 October 1812 to Hannah Blakefield and Anthony Best. And John Blakefield died precisely two months later.

Samuel Best died in infancy in 1813. The couple went on to have a son named William on 23 June 1814. William would bear the surname Scott, because his mother’s relationship with Anthony Best broke down, and she married John Scott in 1816. Anthony Best provided for, and recognised William as his son, until the end of his relationship with Hannah.

A Pardon, respectability and a well-to-do widow.

1815 saw Anthony Best granted an Absolute Pardon – he was close to the expiry of his sentence. He was around forty years old, and described as 5 feet 8 inches, with brown hair, fair complexion and blue eyes.

This was also the first time Anthony Best placed a classified advertisement. He became a passionate classified advertiser for the next 35 years, employing a particular spelling style regardless of accuracy or fashion – the words “negociation” and “expence” would feature in his ads over the years.

In 1816, the respectable community member Anthony Best gave generously to the Waterloo Subscription for “the RELIEF of the noble SUFFERERS under the gallant DUKE of WELLINGTON, on the 18th of June last,” and began a new de facto relationship.

Best’s new relationship was with a widow named Elizabeth Powell (nee Fish)[iv], who had six children, and whose late husband had a farm and a public house. The couple remained together for ten years, but did not marry[v] or have children.

Anthony Best’s gradual climb to respectability was briefly halted in June 1816, when he was convicted of issuing a challenge to, and committing an assault upon, a commercial agent named James Underwood of George Street, Sydney. Best was ordered to pay a fine of £50, and to be imprisoned for a month.

Mr Underwood, acting under a deed, represented the interests of Edward Powell junior, the heir-at-law of Elizabeth’s late husband. Young Edward had gone abroad for a while and Underwood was protecting a substantial portfolio of land, houses and goods. Zealously. Anthony Best may have considered that he had better standing to act for the heir-at-law, and Mr Underwood disagreed. At any rate, after the assault conviction, the public were cautioned against entering into any contract to purchase any part of Edward junior’s portfolio, unless they were dealing with Mr Underwood.

Anthony Best recovered from this setback to be appointed Agent and Overseer for the farm and premises of Mrs Elizabeth Powell, such premises included the very popular Halfway House Hotel on the Parramatta Road.

Over the following years, Anthony Best managed Elizabeth’s business interests, conducted his own business in Sydney, and served as a juror for two Sydney inquests. He petitioned the Colonial Secretary for a grant of land in Van Diemen’s Land, and was granted assigned convict servants.

In 1823, John Scott petitioned the Governor’s Court for child support for William (Best) Scott. Anthony Best had “stoutly resisted” any demands for child support, and the matter had ended up before the Bench. Best’s history with the Blakefields was made public, and Reverend Samuel Marsden had relished the opportunity to depose to the scandalous nature of that relationship. Because the Scotts had not made the correct applications in the past, the Judge could not make an order for maintenance on this occasion.

In 1824, Best’s horse was mutilated and nearly disembowelled in the night, and he offered an 80-dollar reward for information leading to a prosecution. Strangely, it wouldn’t be the last time one of his horses would be sabotaged.

In 1825, Best was a witness to the last movements of the victim in a murder case, but in 1826, his years of business success and increasing respectability ended in spectacular fashion.

The proceeds of crime, mutiny, and Moreton Bay.

On a Sunday night in May 1826, burglars stole about £300 of goods from Rapsey & Mitchell in Sydney. The police rounded up six men they believed to have been responsible for the crime, and then arrested another man for receiving part of the proceeds of the robbery. That last man was one Anthony Best.

The goods found on Best’s premises amounted to half a dozen silk handkerchiefs, which Best claimed to have bought for £6 cash. Whether it had been a pledge in the manner of a pawnbroking agreement, or a purchase of goods, and whether Best knew the material was stolen were the questions upon which the case turned.

Best was found guilty, and tried manfully to arrest the judgment of the court. He brought objections to apparent inaccuracies in the information, and brought claims of parties attempting to ruin him[vi]. All to no avail. He was given 14 years’ transportation. To Norfolk Island.

ANTHONY BEST, whose illicit traffic in the spoils of the midnight robber, excited so much attention, has commenced his tour to the scene of a long period of future labour. The Wellington, bore him from a home, where he might have passed the close of his life in comfortable independence, to the fell shores of Norfolk’s isle, where a weary term of fourteen years, may in the natural course of things, be expected to end his worldly career—with him went also the despoiler of the peaceable — the well-known depredator Edwards, alias Flash Jack, whose repeated enormities have consigned him to a destiny—in this world unaided and unpitied.

The Monitor, 1826.

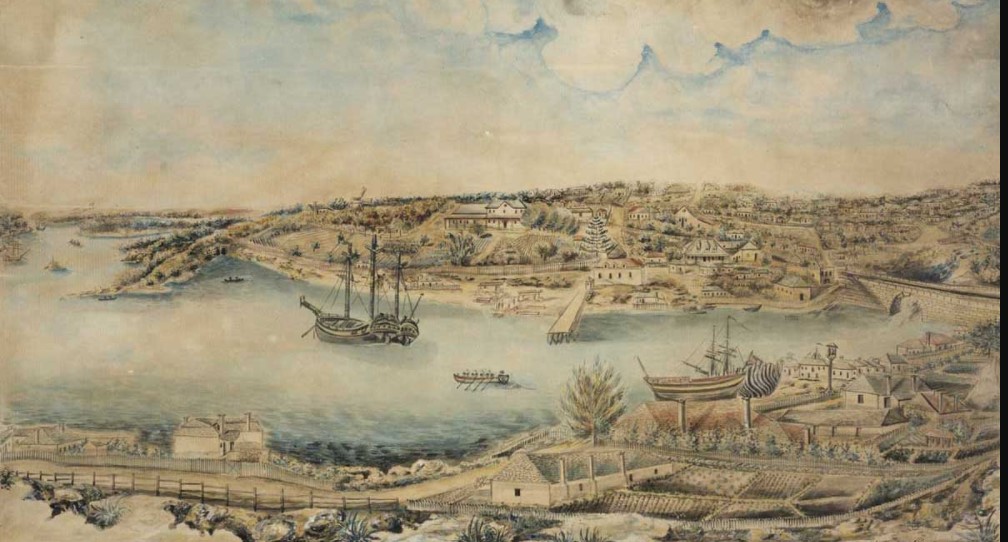

In September 1826, 40 prisoners were taken to the Hulk from Sydney Gaol. They would later board the brig Wellington, and sail for Norfolk Island. The Sydney Gazette noticed that a couple of the men seemed “rather refractory.”

The brig was two days away from landing at the remote penal colony when a group of prisoners took advantage of a lack of supervision on deck, and overpowered the scanty guard and the captain. They set sail for New Zealand, but were intercepted by a whaler lying at anchor in the Bay of Islands. The pirates were eventually overwhelmed, and the two vessels headed back to Sydney.

In February 1827, Anthony Best found himself on board the Phoenix Hulk in Sydney Harbour once again. Still a convict facing a term of transportation, but now something of a hero. He had chosen to resist the mutiny, and had placed himself in a position of personal danger by remaining loyal to the original captain and crew. He knew that if he survived the experience, he would be a marked man among the convicts at Norfolk Island.

After the inquiry into the seizure of the Wellington, Best had his sentence halved to seven years’ transportation. For a man in his fifties, the reduced sentence gave him hope of being able to return to society while he still could. Chief Justice Forbes, having visited the Hulk for the Assizes, recommended that the Colonial Secretary send Best to Moreton Bay instead of Norfolk Island. He arrived at Brisbane by, of course, the Wellington on 20 July 1827.

In September 1828, Anthony Best was taken to Sydney as one of the witnesses in the trial of John Rothwell (or Rockwell) for a serious assault on Patrick Cantwell. A local journalist was astonished at the change in him[vii]:

The appearance of Best in walking through the streets on Wednesday, on his way up to the Courthouse, was remarkably striking. Those who had seen him two years ago walking through Sydney in health and spirits, recognised the change. Best, during his “rustication,” has become so altered in appearance, that many to whom his person was not known on the above occasion, could scarcely identify him.

The Australian, September 1828.

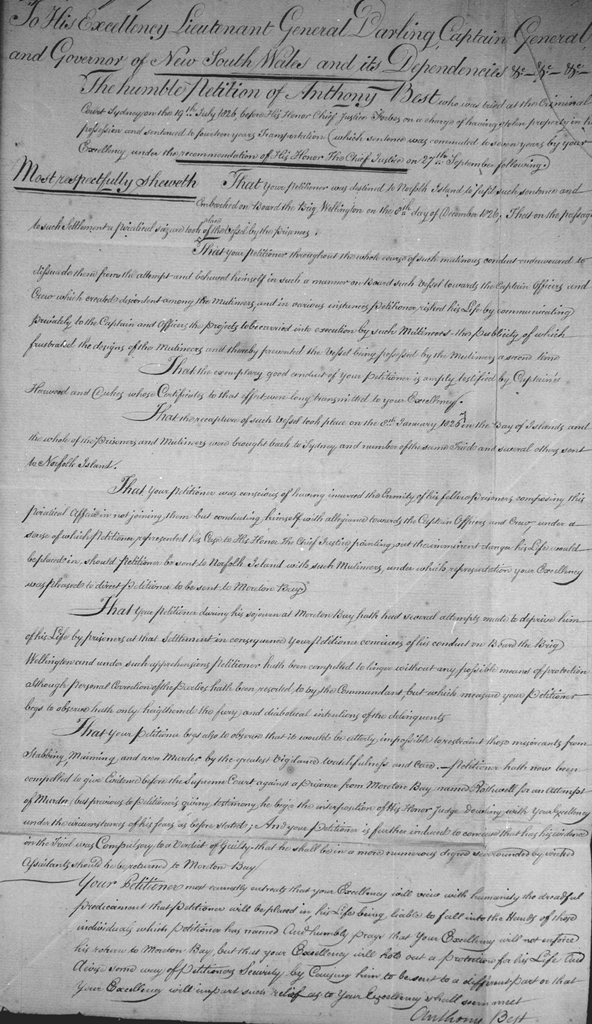

Whilst on board the Hulk awaiting his return to Moreton Bay, Best penned a Petition to Governor Darling. He beseeched His Excellency not to return him, fearing that “wicked assailants” would attack him there. It’s an exquisitely penned document, presumably by a master petition-scribe (Best’s own writing was legible, but not decorative by any stretch of the imagination). His Excellency sniffed that he had received no evidence of the “hazards of which he complains,” and sent him back to Moreton Bay.[viii]

Best behaved himself at Moreton Bay – he did not appear on lists of prisoners punished, and wrote no more petitions.

Return to Sydney and marriage.

1833 was quite a year for Anthony Best. In February, his long-lost wife, Margaret Bennington Best, died in Beverley. His sons from that marriage were now adults. No doubt the news took a long time to reach Best at Moreton Bay.

He became ill with tussis and spent the month of March in the Moreton Bay Hospital. He was discharged on 7 April 1833 “to light work permanently.” He endured another few months and was discharged to Sydney on 16 August.

Anthony Best had made a deed (in 1826) to transfer ownership of his property in Kent Street Sydney to agents Beeson and Weedon[ix], in trust for his children. His return to town caused the agents to caution all interested parties against paying rents to Mr Best. They had done this in consequence of advertisements taken out cautioning the public against paying monies to them, and directing payments to one Mr Anthony Best. Taken out, no doubt, by one Mr Anthony Best.

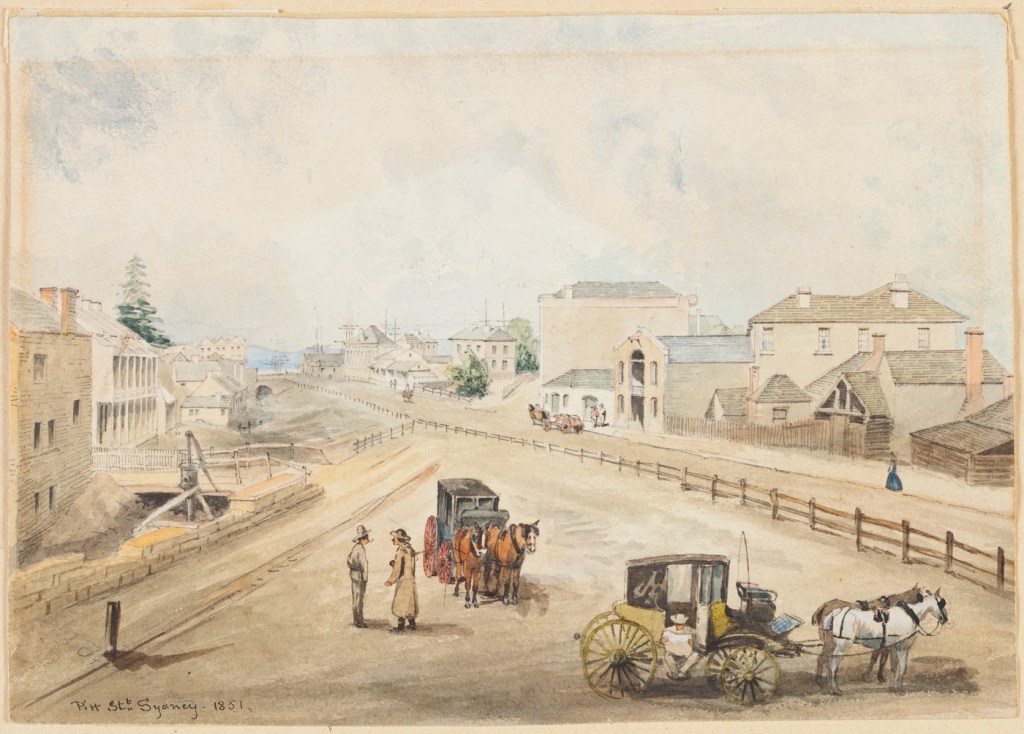

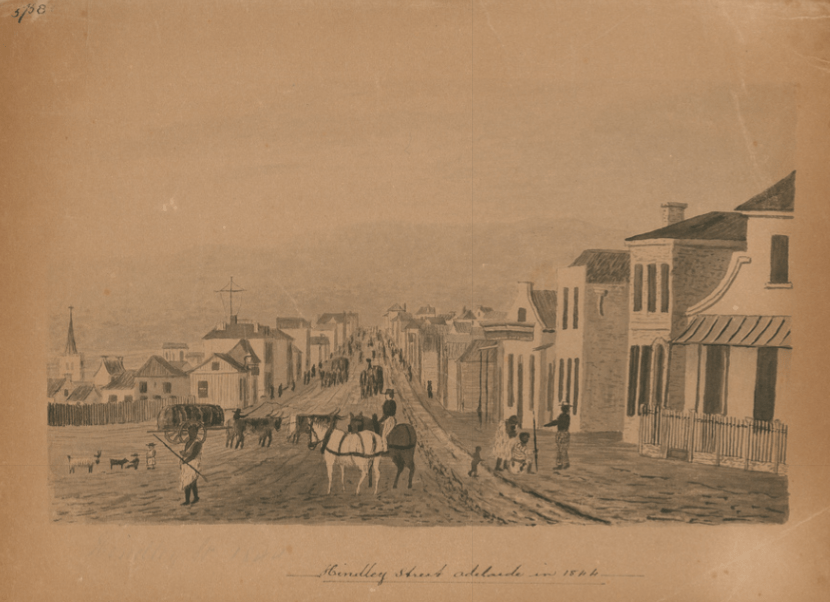

Pitt Street Sydney, then and now.

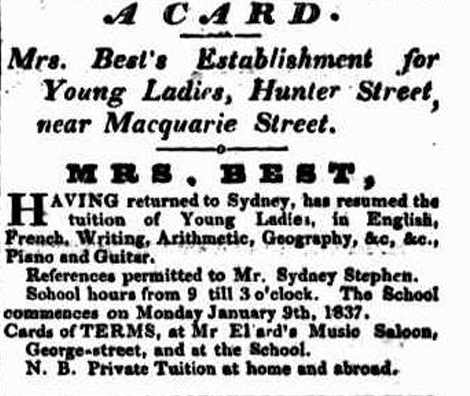

A man with aspirations to resume his former life could do with a wife. Now that he was officially a widower, he found a lady to join with in holy matrimony. Mrs Mary Pearson[x] was a lady who taught Spanish Guitar, Pianoforte, the French Language, Geography and use of the Globes from her premises at 105 Pitt Street, Sydney. She was a free immigrant, allowed to have convict servants, and carried about her an air of great respectability. Plus, that house in Pitt Street.

On 15 April 1834, Anthony Best and Mary Pearson were married at the Scottish Church in Sydney. On 25 November 1834, Anthony Best cautioned all persons against giving Trust or Credit to his wife, Mary Best, who had left him without cause or provocation. What happened was not made clear for another decade.

Tasmania and horseflesh.

Mrs Best turned to boarding-house keeping and tutelage in Pitt Street, at one point setting up Mrs Best’s Establishment for Young Ladies (French, Geography, Globes etc). Sometimes she advertised under the name Pearson.

Mr Best relocated to Van Diemen’s Land, taking with him the assigned convict servant of Mrs Best, one Grace Bryant[xi]. He lived with her there for two years, before the Police located her as a runaway convict, and she surrendered herself into the custody of New South Wales police. While some witnesses spoke of their relationship as man and wife, Hannah told the police that “Mr Best had always been very kind to her and behaved to her like a father.”

In Launceston, Anthony Best was able to set up in business on Wellington Street, and began horse-trading. He had a fine sire named Farmer’s Glory, who stood at stables all over the colony, and life continued agreeably until 1838, when Farmer’s Glory died of poisoning, and Best became involved in a disagreement with a Captain Kelham in July. Best was bound over with a surety to keep the peace towards the captain; while another person, one Charles Warrel, was gaoled for three days for calling Best’s housekeeper a “prostitute.”

The dawn of 1839 saw Best involved in a legal case against a local grandee who had decided to take possession of his land, bung a lot of convict huts on it, and strip it of all the timber. Best was awarded damages against the astonished grandee, who believed his position gave him automatic right to use the property.

Adelaide, a new family, a ferocious dog, and an incendiary haystack.

Perhaps it was time for a change. Best sold a large property, stables and four-bedroom house in February, and in March departed for South Australia on the Brazil Packet.

Anthony Best set up a store (with stables of course) in Morphett Street, and began trading. He added premises in Hindley Street. Best was approaching 70 years of age, but cheerfully carved out a new life: he became a well-known businessman in Adelaide and famously had the most ferocious (guard) dog and the biggest haystack in town. At one point, his haystack was destroyed by an arsonist, and he responded by creating an even larger hay edifice, to the alarm of his neighbours, who had thatched roofs.

He began a new family with Grace Sloggett,[xii] welcoming four children – Sophia, Margaret, Anthony and Elizabeth.[xiii] He involved himself in politics[xiv], horse racing, horse breeding and litigation. Through his many court cases, we find that he let his pigs stray, only to have them attacked by a neighbouring ostler (called “Billy the Boy” – the ostler, not the pig). From another case, we learn that Best had a nephew staying with him who rejoiced in the name James Cobbledick. Life was busy, but Best was the master of making new starts, and was happy. Then, disaster struck.

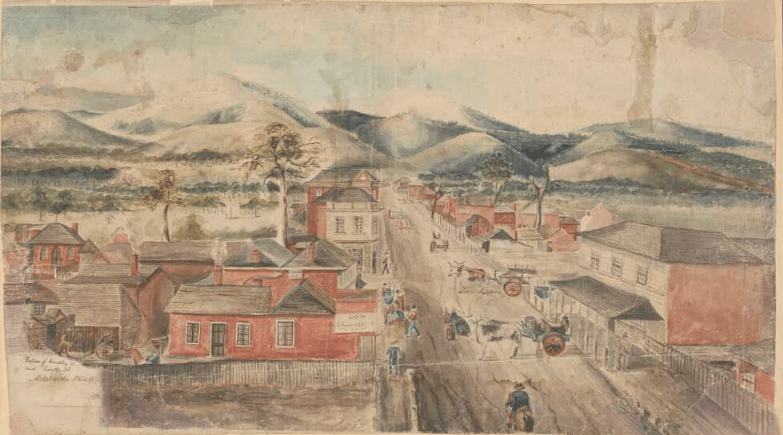

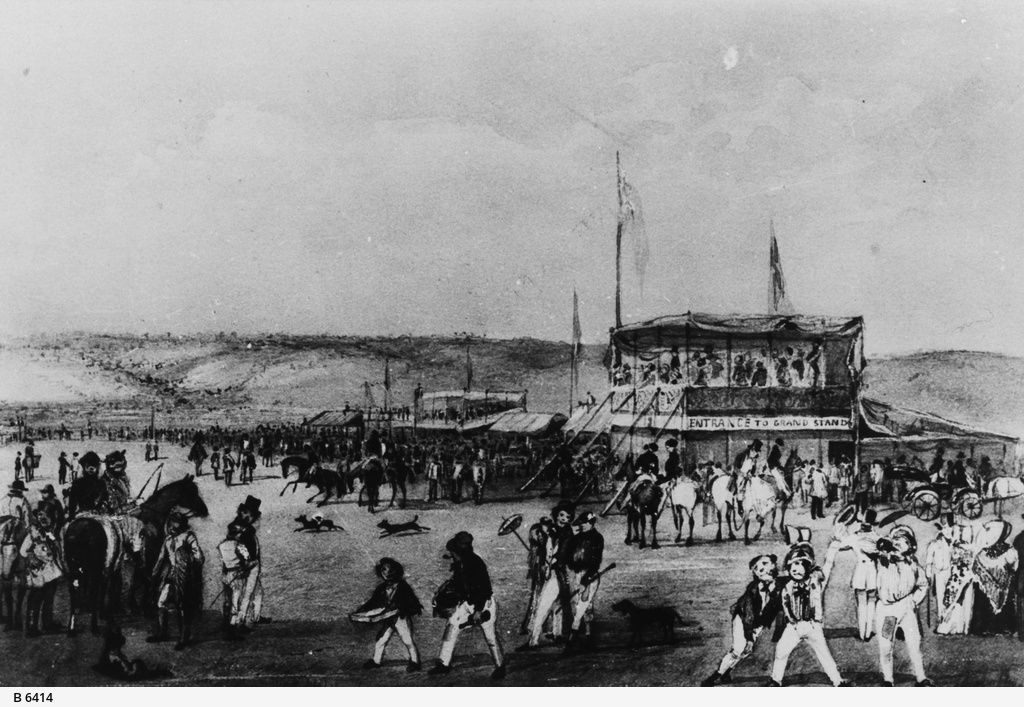

A race meeting in Adelaide. No doubt Anthony Best would have attended.

A blast from the past.

In the shipping news of 26 January 1844, Adelaide residents would have been surprised to notice the arrival of one Mrs Anthony Best on the schooner Hawk. Wasn’t Mrs Anthony Best living in Hindley Street, with her husband and growing family? Odd.

This new Mrs Best turned out to be the existing Mrs Best, and she wanted her husband to pay her maintenance. Mr Best refused to maintain Mrs Best. Mrs Best went to Court. Mr Best’s private life would become very public indeed.

Mrs Best’s Case:

When Mary Best appeared in the Resident Magistrate’s Court in February 1844, the court reporter noted that she was “a very respectable-looking woman.” She said that she had come to Sydney as a cabin passenger, not steerage, and had earned her own living keeping a boarding-house (respectable), and as a governess and music teacher to respectable (of course) families. She had married Best at the Scottish Church in April 1834. In November 1834, she spoke to Anthony Best about his liaison with her convict servant. She said that Best turned her out and refused to let her return, but did permit her to have her piano, music books and trunk. The economic situation in New South Wales had declined in recent years, and she was no longer able to maintain herself. She had written to Mr Best for support, but he would not acknowledge her.

Mr Best’s Case:

Anthony Best claimed to have gone to the Scottish Church at Mrs Best’s insistence, and that he was drunk when he signed the marriage certificate. He had only taken her on after she had promised to behave herself, but she was “addicted to drunkenness.” Best stated that Mrs Best could drink a bucket of rum a day, and that he turned her out of the house because of her habitual drunkenness and other unsteady behaviours[xv]. He questioned the validity of marriages conducted by the Scottish Church in the eyes of the Church of England, and the wording of the statutes.

“l shall not support her, I have not anything to give her. All that I had has been made over to those to whom it belonged. If you press her on me, my door is open. She must come to the swamp where I am, and live on potatoes and water.”

Anthony Best, claiming to be a poor man.

The matter dragged on for eighteen months. At one point, Best opted to go to gaol for three months rather than pay maintenance. After his imprisonment, the matter was rather grudgingly settled, probably because 73-year-old Best wasn’t in the best condition to spend time in durance vile.

Peace at last.

Once Mrs Best was maintained and dealt with, her estranged husband sired a son and daughter with Grace Sloggett, bought and sold horses, bought and sold land and litigated with his usual zeal. He sought a publican’s licence in March 1850, but was refused, not least because of his de facto relationship with Grace. Best replied, “Very well, I will sell beef and bacon and give my rum away for nothing (laughter).”

This plan did not come to fruition. After surviving two marriages, eight children (who ranged in age from fifty years to eighteen months), forty years in the colonies, two terms of transportation, and one mutiny on the high seas, Anthony Best died on 16 March 1850.

“The old gentleman called at the office of this paper, and purchased the Observer of that day, in his usual health and spirits. He went to Mrs Allen’s, at the “Southern Cross Hotel,” in King William-street, called for a glass of ale, and kindly expressed his sympathy for Mrs Allen’s recent bereavement, adding, “He was a good fellow. It’s wonderful how these things are ordered. Here’s a wicked old sinner like myself, alive and hearty.”

“In two minutes after, the speaker was in eternity. He went outside to mount his steeplechaser “Bachelor,” by means of a stool, rendered necessary from his corpulence. As Mr Best gained the saddle the stool knocked against his horse’s legs, causing it to rear, and the poor old man, having no command of the reins, fell heavily on his head, and broke his neck in the fall, of course dying instantly.” The South Australian Register.

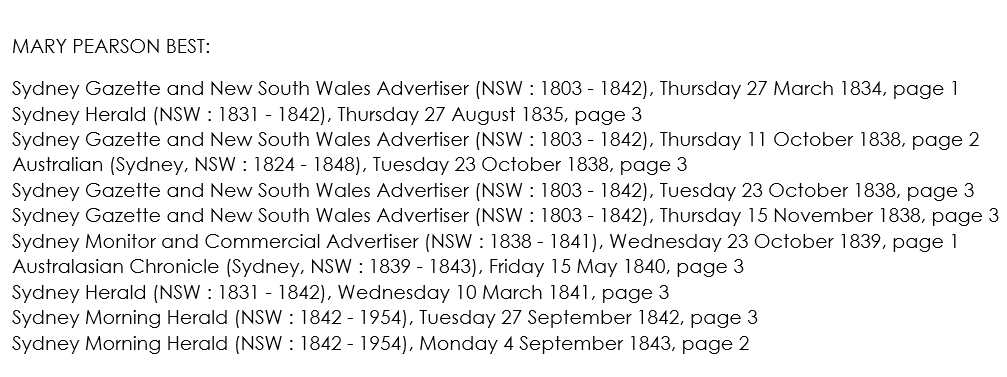

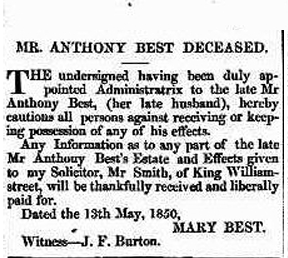

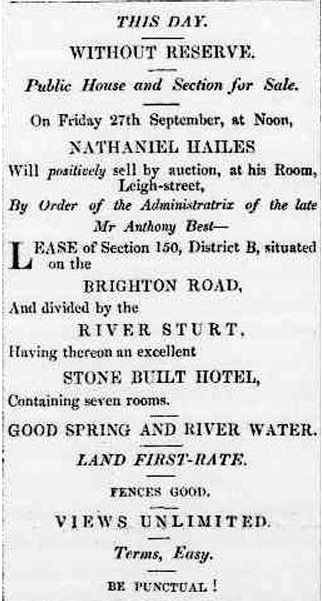

Mr Best was gone, but decidedly not forgotten. Within seven days of his passing, Mrs Anthony Best took out the first of a long series of advertisements designed to secure every last piece of his estate:

CAUTION TO THE PUBLIC.

THE Public is hereby cautioned against purchasing or receiving any goods and chattels, or other property of Mr Anthony Best, of Cowandilla, my late husband, deceased, as I have not authorised any person or persons to dispose of the same, or any part thereof; and any person or persons purchasing or receiving the same will have to abide legal consequences.

MARY BEST, Administratrix of the said Anthony Best, deceased. 10th March, 1850.

Mrs Best spent the following two years before the Supreme Court and Equity Courts of South Australia, vigorously pursuing creditors for everything from the profits of horse sales[xvi] to the ownership of two millstones. The heir-at-law turned out to be living in England, being the now 50-year-old eldest son of Anthony Best. From the first Mrs Anthony Best.

[i] Mary Ogle was married to one Joseph Ogle, who at the time was suspected in being involved in the robberies. He was wanted for escaping from the Royal Westminster Militia, writing a threatening letter to a constable, and “lurking about the town and neighbourhood.” His aliases included “Fighting Dick.”

[ii] A cordwainer was a type of shoemaker, but one whose craftmanship permitted him to work on new leather in order to make new shoes. A cobbler could only work with old leather.

[iii] Hannah Clothier was born in July 1775 at Stoke Sub Hamden Somerset. In 1804, She was convicted at Gloucestershire of stealing mill-flocks (wool scraps) and given 7 years’ transportation. She arrived in 1806 on the William Pitt, and married John Blakefield (1763-1812) at Parramatta NSW. The Blakefields had 2 sons – Charles (1807-1878), Thomas (1810-1811). Hannah had Samuel with Anthony Best on 14 October 1812. Her husband John died on 14 December1812 at Parramatta. With Anthony Best, she another son (William) on 23 June 1814, and then a daughter with John Scott (b 1778) in 1815. In 1816, she married John Scott at Windsor. She died aged 85 in 1860 at Patricks Plains.

[iv] Elizabeth Fish was born on 12 March 1771 in Dorset. She had a son at the age of 20, who died on the voyage out to New South Wales. Elizabeth arrived as a free settler in 1793, and married Edward Powell. She had six children with him before his death in 1814. She married James Moore in 1829, and they passed away within months of each other in 1836.

[v] The couple had approached Reverend Samuel Marsden, who refused to marry them (still disapproving of Best’s relationship with Hannah Blakefield before the demise of her husband).

[vi] One of the robbers had been overheard to say that he would ruin Best by having him convicted.

[vii] Best was a grey-haired man of 56 when he arrived at Moreton Bay. Several spells in the Hulk and life at a penal settlement had caused him to lose a lot of weight.

[viii] Best had been a witness in a summary hearing at Moreton Bay, but it was hardly likely to incur retribution – he’d seen Morgan Edwards cutting off two of his own fingers.

[ix] Beeson and Weedon would spend the next few years trying to untangle Best’s property affairs.

[x] Often spelled “Pierson.”

[xi] Grace Bryant (b. 1800) was convicted of manslaughter and robbery at Exeter, and transported in the Roslin Castle 2 in 1830. Bryant had been a sex worker, and was one of a group charged when a client died in the course of a robbery in a house of ill repute. Grace had married on arrival in the colony, but her husband was out of the picture, having been imprisoned for larceny.

[xii] Grace Sloggett (1809-1887) was born in February 1809 in Altarnun, Cornwall. In April 1839, she left Launceston for Adelaide. She was in a relationship with Anthony Best from May 1839 until his death. The couple had four children. Grace Sloggett passed away in February 1887 in Adelaide.

[xiii] At this time, the children of his marriage in Yorkshire were in middle age, and those from his Parramatta years were in their thirties.

[xiv] Mr Best was prone to attending meetings, and giving rambling speeches with biblical references, to the confusion of those present and the mirth of newspaper writers.

[xv] There may have been some truth in the allegations of drunkenness – Mrs Best had “servant problems,” and a lot of those problems arose from Mrs Best’s behaviour. In 1838, “The Assistant Chief Constable and the Inspector of the District both went forward and bore testimony to the general drunken habits of the woman’s mistress, whom they stated they had frequently seen intoxicated.” The Magistrate hearing one case threatened to write to the Governor citing Mrs Best as a “very unfit person to be entrusted with servants in future.”

[xvi] The horse in question was named “Botherum,” because Mr Best had declared that it would “Bother ‘em” on the racecourse. Boom-boom.

Sources: