A small revolution took place in the 19th century workplace. Women started to be admitted into professional and administrative fields – very slowly, and very quietly. The women were quiet about it – the men who faced what they believed to be the erosion of the natural order of things were not quiet.

This is a photo essay on the women at work in early Queensland, from the traditional fields of employment to the most unladylike indeed.

Servants.

Most of our immigration was based on the recruitment of servants – men to labour, and women to help the household. Beginning with assigned servants from the convict classes, immigration developed, with fleets of ships landing what were sincerely hoped to be sober, hard-working artisans, labourers and servants.

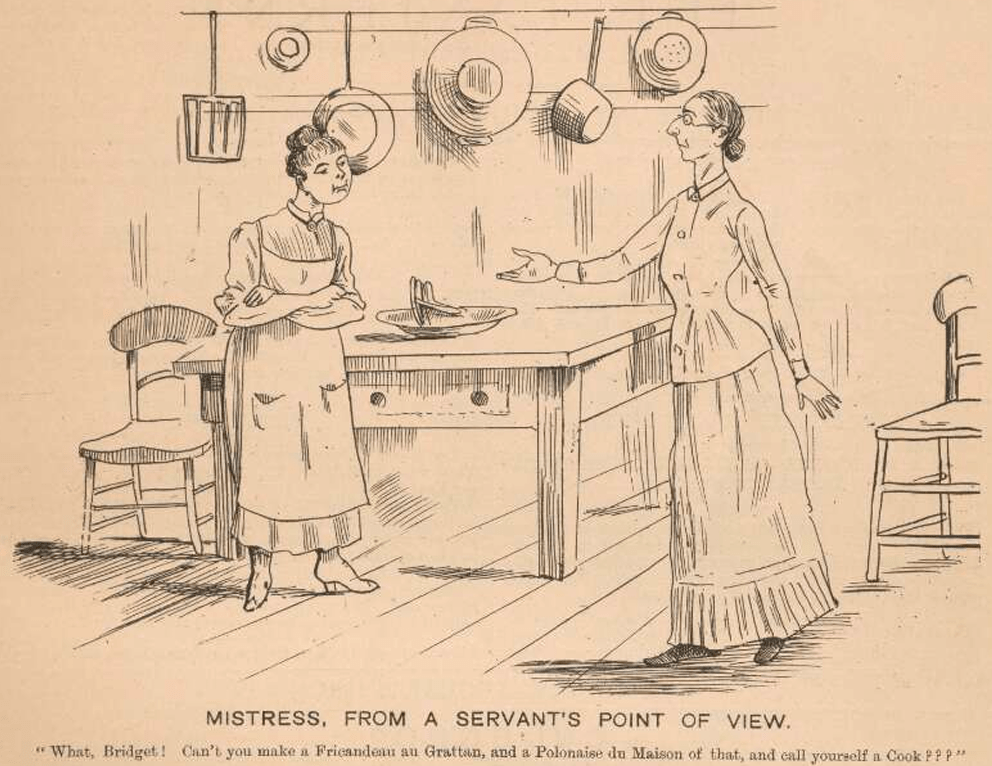

The positions vacant section of the newspapers teemed with offers of work in service for women, but these jobs tended to be thankless and poorly-paid domestic labour. Female servants were often depicted in cartoons decrying their general slovenliness and/or incompetence. The cartoon below, from the Lantern magazine in 1884 flips the usual scenario a tad.

General domestic servants were very rarely photographed in Australia in the 19th century, particularly in Queensland. The only exceptions I could find were some very depressing photographs of indigenous children and teens, posing very uncomfortably in the starched aprons worn by genteel servants.

If one, however, was well-to-do, one’s family picture may contain a senior house servant or so, or a governess. On the hierarchy, these employees were seen as desirable additions to a group photograph – a testament to one’s social standing.

The teaching profession.

The first teacher in Queensland was Mrs Roberts, who educated the children of the military who ran the Moreton Bay convict settlement. Once free settlers arrived, what education there was came from church schools or genteel establishments offering “the usual branches of polite English Education, including music and drawing.”

Once a system of government-run education was introduced, educated and trained women were dispatched throughout the Colony to drum some arithmetic and literacy skills into the tots of Queensland.

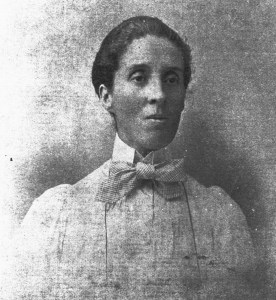

Two educators who left their mark. Left: Mary Emma McConnel (nee Jordan) was a teacher and women’s labour rights activist in the 1890s. Right: Eliza Ann Fewings, was the founder and first principal of the girls’ school that became Somerville House.

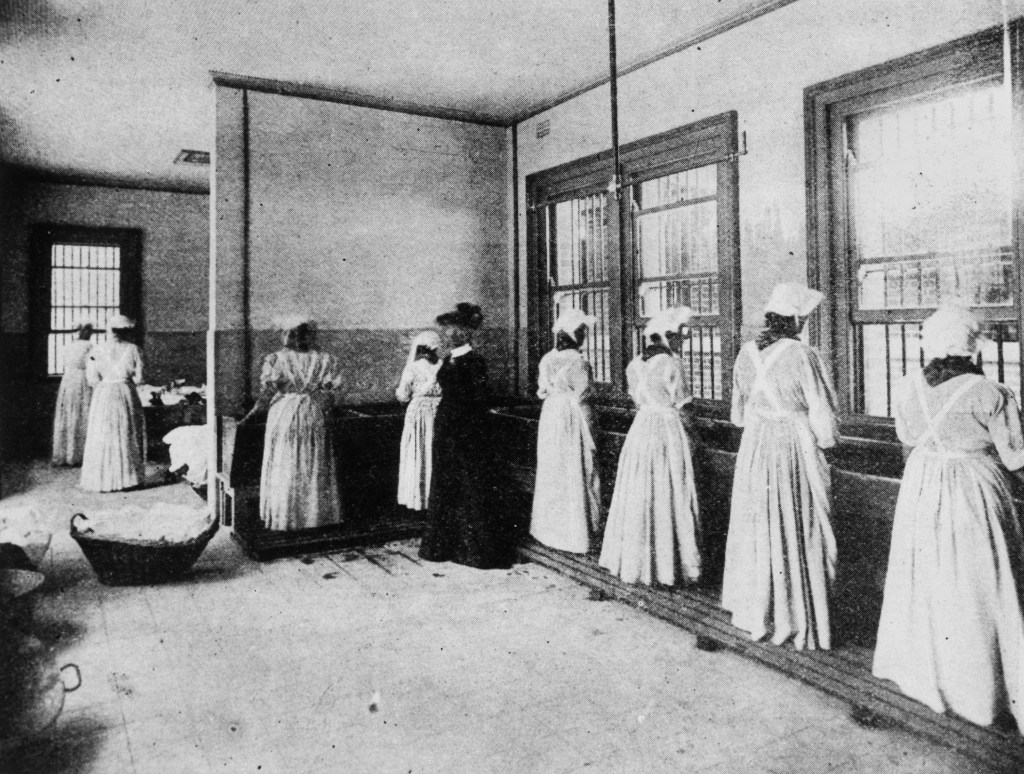

The nursing profession.

The other non-domestic employment opportunity for young women in the 19th century was the nursing profession. Thanks to Miss Nightingale, nursing gradually became respectable and a training element was introduced. Discipline seemed to be more important than practicality though, as evidenced by the starched caps and aprons and general lack of levity displayed.

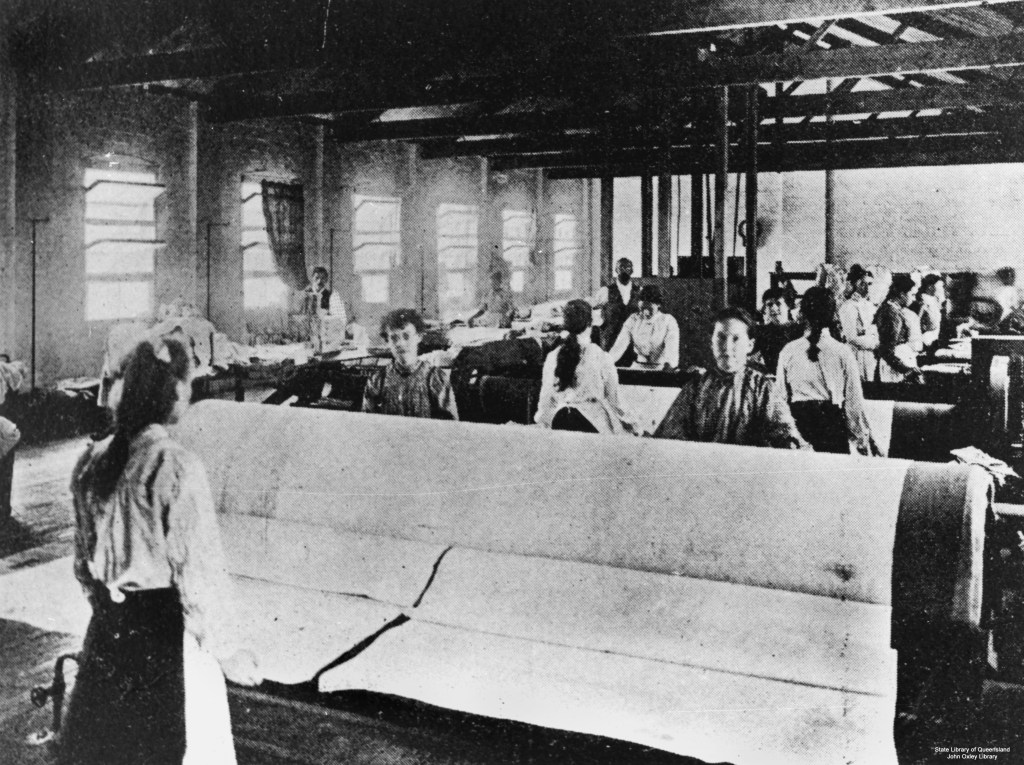

The hard labour of 19th century women.

There were hard-working women in factories and fields too. Some, like the South Sea Island women and the prisoners, had no option but to perform hard manual labour.

As the century ended, technology beckoned.

By the end of the 19th century, women who were blessed with both concentration and patience were able to become telephonists. It was less brutal than working in a steam laundry, less exhausting than nursing, shop counter work and domestic chores. Women were able to enjoy stable working hours and conquer new technology.

The first female Doctor.

Dr Lilian Cooper was registered as Queensland’s first female doctor in 1891, and joined the Medical Society of Queensland two years later. Her consulting rooms were in George Street, and she became a familiar sight in Brisbane city, piloting a sulky to her daytime calls, and a bicycle for night calls.

The path to properly paid, worthwhile work was a long and difficult one for Queensland women. The attitudes of society to women’s work beyond domestic chores were hardly encouraging:

So the ladies are beginning to take the medical profession by storm. Apothecaries’ hall has been forced to admit Miss Elizabeth Garrett within its sacred precincts. Nor this alone: the pertinacious young lady, after duly listening to lectures, has bravely faced the examiners, and passed in triumph. If she is equally successful in her future examinations, she will soon be Dr. Elizabeth! The prospect is serious.

The simple truth, which ambitious Miss Garrett has yet to learn, is that women are not fit for professional work. Imagine a woman pleading a cause – or putting a regiment through its drill – or preaching a sermon – or commanding a ship.

Queensland Times, 1864.

For better or for worse the market is inundated with female clerks and female “counter jumpers,” while men stand by and wonder why it is impossible to obtain good female servants except at famine prices.

The Week, 1879.

While one feels for the men standing by and wondering why servants cost so darn much to hire, it is satisfying to know that women can now plead a cause, preach a sermon, drill a regiment or command a ship if they wish.

- Week (Brisbane, Qld.: 1876 – 1934), Saturday 8 February 1879, page 23.

- Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser (Qld.: 1861 – 1908), Thursday 7 July 1864, page 4.

- All images are part of the State Library of Queensland’s digital collection, and are out of copyright.