Churches.

During the convict period, prisoners were mustered on Sundays and had Divine Service read to them whether they liked it or not. Moreton Bay briefly enjoyed the services of a Reverend Vincent, but he only stayed several months, returning to Sydney after suffering a bad case of Commandant Logan.

Once free settlement began, houses of worship from the rough and ready to the Gothic and Godly were built. Here are some Brisbane churches of the 19th century.

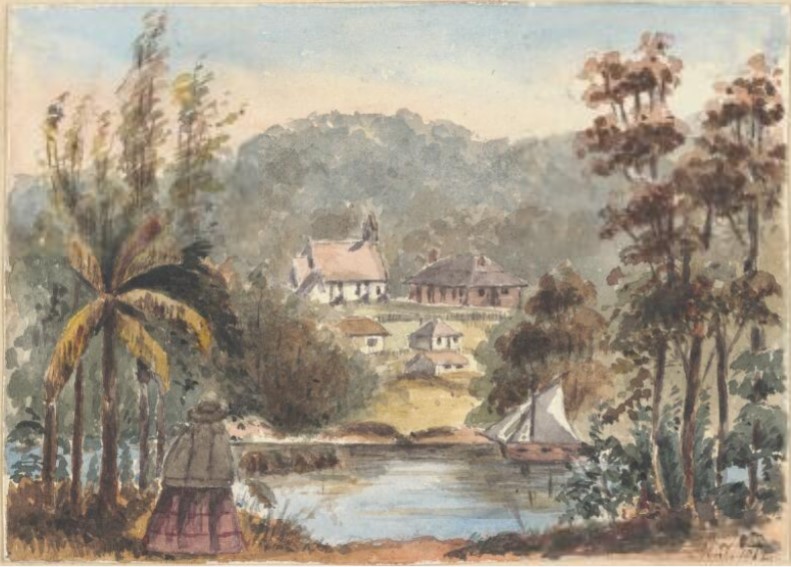

The first St Stephen’s Cathedral, also known as Pugin’s Chapel, built 1848-1850. (Artwork part of the QAGOMA collection).

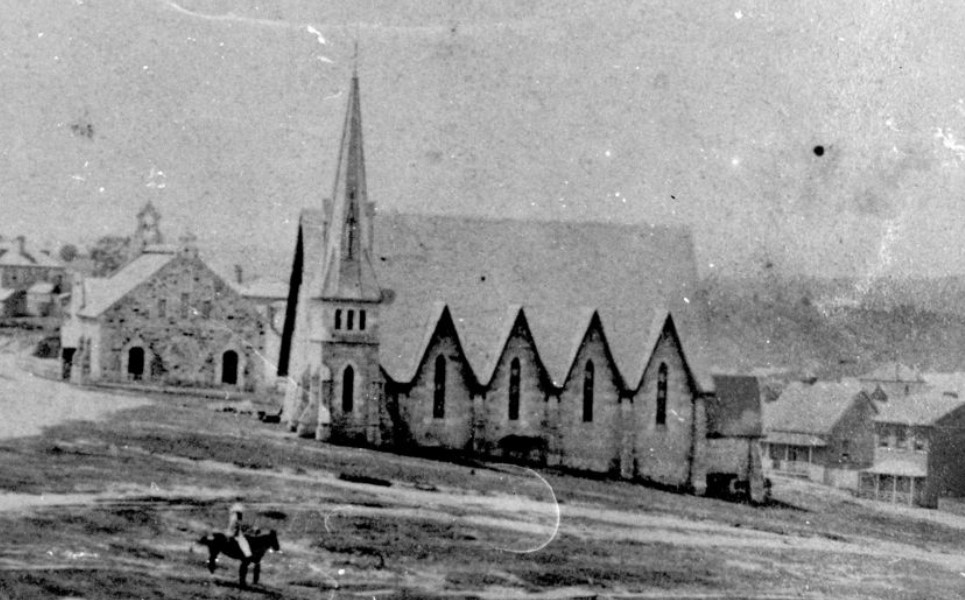

Wickham Terrace churches in the 1860s. Left: The first All Saints Anglican Church, Wickham Terrace. Right: First Wickham Terrace Presbyterian Church.

Left: the City Presbyterian/Congregational Church. Right: Holy Trinity Church, Fortitude Valley.

Left: Nazareth Lutheran Church. Right: South Brisbane Presbyterian Church.

The Convict Era.

Between 1824 and 1839, 2121 convicts were transported to Moreton Bay. Nearly 200 were recorded as having died at the settlement (through disease or accident), 12 were drowned, and a similar number were reported as having been killed, either by indigenous people or other convicts. Many convicts absconded from the settlement, and it is likely that most did not survive.

Two important convict-built structures survive in Brisbane today – the Windmill and the Commissariat.

The Cribb family – Lang’s Immigrants.

Few families had such a lasting impact on the young colony as the Cribb family. The impressively-bearded Robert Cribb (1805-1893) arrived on the Fortitude in 1849. Brother Benjamin (1807-1874) brought his family over on the Chasely. Both were dedicated to Dr Lang’s proposal that skilled Christian immigrants could make a positive impact in “Cooksland.”

Robert based himself in Brisbane, became a land agent and merchant and entered politics. Benjamin founded Cribb & Foote at Ipswich, supported immigration, and served in Parliament and as an alderman. The descendants of both Cribb brothers had substantial business and political careers. None could quite match the original Cribb beardiness though.

Courthouses.

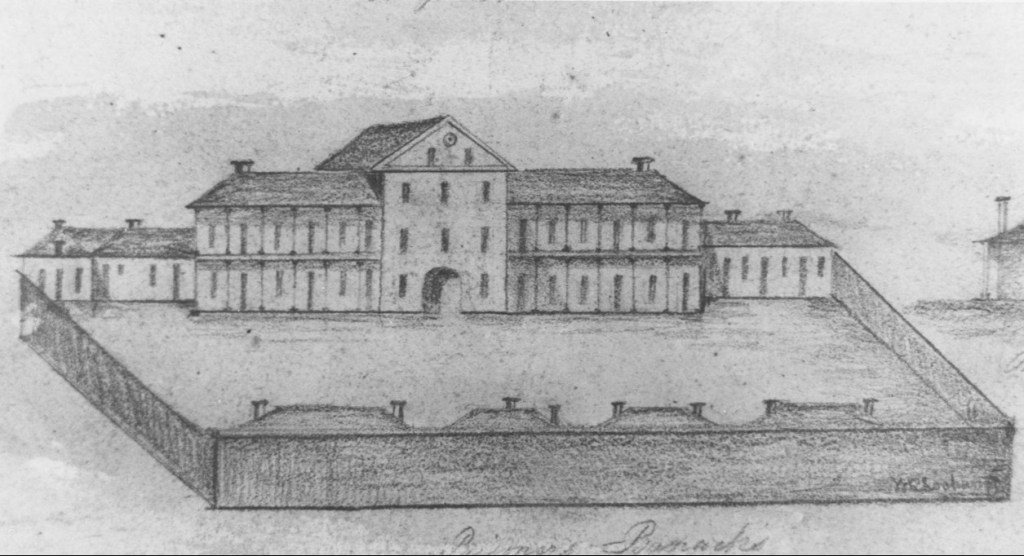

The original courthouse was also the Prisoners’ Barracks, built in the late 1820s. Commandants from Logan to Gorman held inquests, courts of inquiry, summary trials and committal hearings in the building. Two convicts were executed there, and countless others suffered corporal punishment on the triangles in its grounds.

When Moreton Bay opened to free settlers, the Barracks were used for the Courts of Petty Sessions and later for the Circuit Court. The second picture of the Barracks is the clearest view of the building we have before it was demolished.

A new Supreme Court Building ushered in the 1880s. There were arches, verandahs and some splendid sandstone work, but, as the second photograph shows, it was a wee bit grand for its surroundings at first.

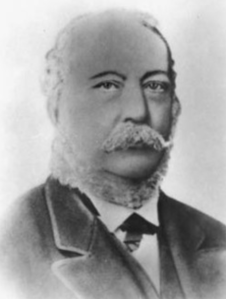

William Wellington Cairns, Governor.

Sir William Wellington Cairns (1828-1888) was Governor of Queensland from 1875-1877. Cairns’ ongoing ill-health and naturally reserved manner prompted one local to remark, “He looks like a Mute at a funeral, and does not seem a very convivial individual.” Sir William’s term was cut short because Queensland’s tropical climate was ruinous to his health. Queensland thoughtfully commemorated Sir William’s brief stay by naming a decidedly tropical town in his honour.

Dr Kearsey Cannan.

Dr Kearsey Cannan (1815-1894) was the second private practitioner in Queensland’s history, after Dr Keith Ballow, who had been attached to the convict settlement. Cannan had several government appointments, notably to run the new Woogaroo Asylum. Cannan lacked the temperament and management ability for such a post, but his subsequent work in private practice was considerably more successful. He advocated for benevolent associations, and more often than not, he treated the poor for free.

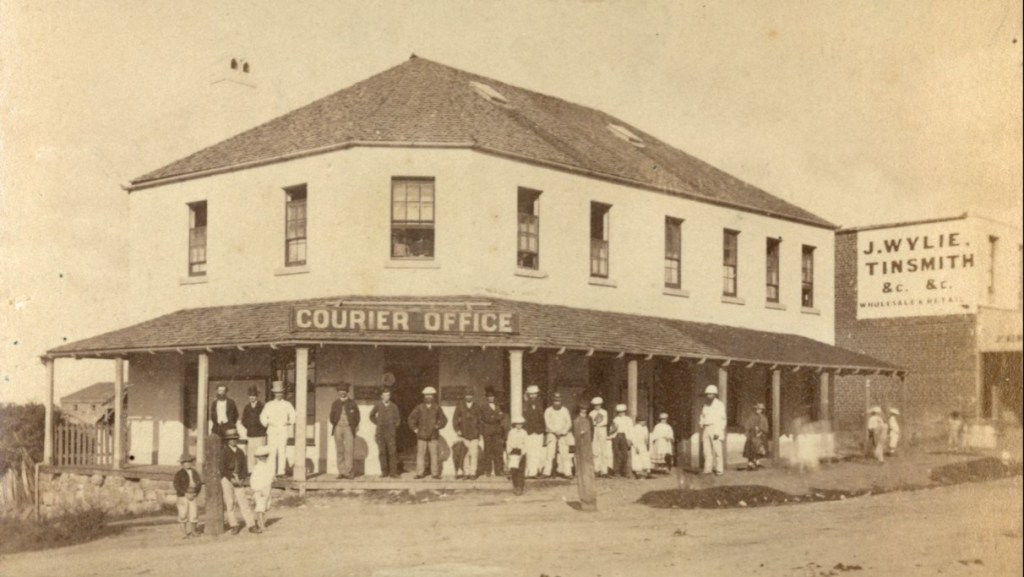

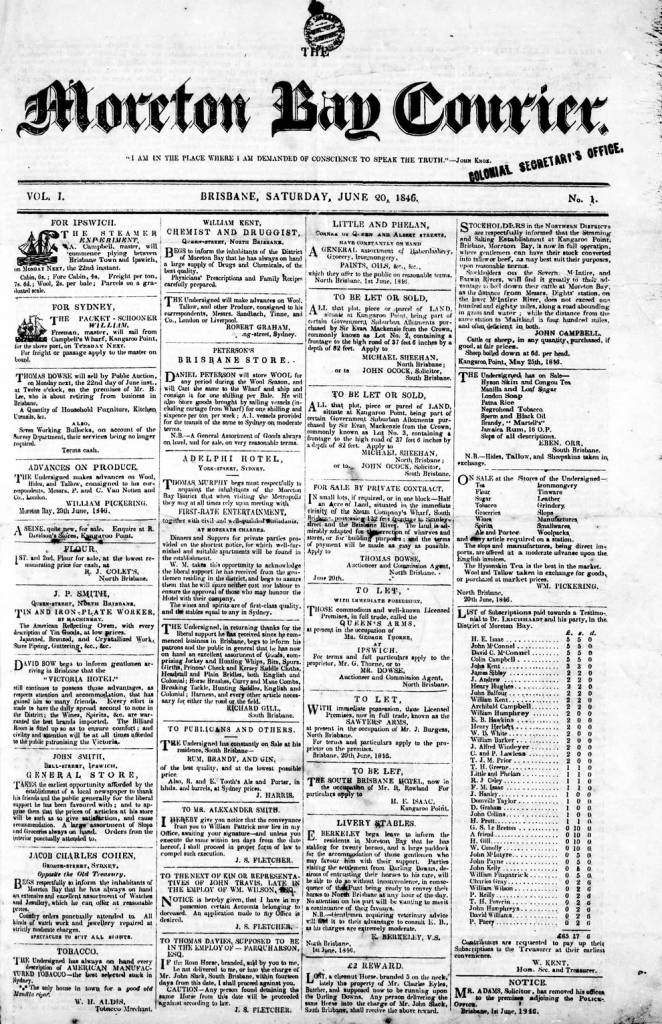

The Courier records and reflects the times.

A new township needed a newspaper, and in June 1846, the Moreton Bay Courier was published. It began as a weekly paper, with special editions created when major news broke. The Courier is still published but no longer in broadsheet form. Its archives provide an astonishing insight into Queensland through the years – for better or for worse.

The Cox murder and the non-fiction novel.

IT is our painful task to record in this day’s publication the perpetration of a frightful murder —committed under such circumstances of evident barbarity as are rarely paralleled in the history of crime … George Cumming, a joiner, residing at North Brisbane, stated that on going down to the river on Sunday morning, between seven and eight o’clock, he discovered the lower portion of a human body lying on the river bank, near Rankin’s fence, considerably below high water mark. He immediately after discovered the other portion, lying at a distance of about two or three yards, without the head.

Moreton Bay Courier, Saturday 1 April 1848, page 2.

A sawyer named Robert Cox was found murdered on Sunday 26 March 1848. He’d been drinking (heavily) with a group of men, including a man named William Fyfe, who was quickly arrested and charged with the crime. Cox and Fyfe had both been convicts at the Moreton Bay penal settlement, nearly 20 years before, and were known to each other. Fyfe was convicted and executed in June 1848, in Sydney. He protested his innocence until the end.

In 1997, almost 150 years later, the late Rosamond Siemon wrote a book called “The Mayne Inheritance,” in which she proposed that a young Irish butcher named Patrick Mayne murdered Cox and stole a large sum of money from him. A year after the murder, Mayne purchased land and set up a butcher’s shop in Queen Street with his ill-gotten gains. In 1865, Mayne died at the age of 41, and Siemon stated that he had confessed to the murder as he lay dying. In the decades that followed, two of Mayne’s children suffered from mental illness and died prematurely. The other two children – James and Mary Emelia – did not marry or have children. They bequeathed the family fortune to found the University of Queensland. The Mayne inheritance, according to Siemon, was both the congenital mental illness, and the charitable bequest.

There is no evidence that Cox had money, that Mayne was the killer, or that Mayne used anyone else’s money to start his shop. When pressed by a largely sympathetic fellow author, Ms Siemon admitted that there was no proof of a deathbed confession. Dr James Mayne did not marry: he may or may not have been the marrying kind as they say, and Mary Emelia lived out her days quietly, with a small circle of friends and rather a lot of money. Whether the two surviving Mayne offspring feared passing “madness” down to any progeny is unknown.

It’s still a great story, and to this day, local tour guides cheerfully rattle off the Mayne Inheritance tale to suitably impressed tour groups as if it was established fact. It suppose that it’s more interesting than a drunken murder and a local butcher who became an alderman and died young.

The Mayne Inheritance, Kangaroo Point 1852 by C Martens, and the approximate location of the Bush Inn, Holman Street, Kangaroo Point. (Google Maps).

Sources:

The Moreton Bay Courier.

The Australian Dictionary of Biography.

Wikipedia: The Mayne Inheritance.

Hearsay.org.

Images are taken from the State Library of Queensland, the National Library of Australia and the New South Wales State Library.