Guns were a dodgy prospect in the 1840s – they seemed to go off accidentally in all sorts of situations. James McClelland was cleaning a pistol loaded with ball when it went off and injured him in the thigh. Pierre Louis Raul was walking through long grass carrying a gun loaded with buckshot when the gun became caught up in the grass. Pierre ever so sensibly put his hand over the muzzle as he tried to disentangle the weapon from the grass, and was rewarded with a shattered hand when it discharged. William Colquhoun, a sailor on board the Secret had only to stand on deck over a gun loaded with duck shot for it to go off and lodge rather a lot of said shot in his legs.

James, Pierre and William all survived their encounters with temperamental self-firing guns, and only spent a month each in the Brisbane Hospital having bits of shot painstakingly tweezed away, and combating infection.

Another man was not quite so lucky. He survived, but it was a hellish road to recovery. And he spent four years in hospital. When he finally emerged, it was said that he had been restored to the world.

A Leicestershire man on the Pine River.

William Mason was from an old and much-respected Leicestershire family, at least eight generations of which had entered and exited this life in services held at St Mary’s Walton-on-the-Wold. William was christened there around 1819, a younger brother for Luke Steward Mason, who had been born in 1809.

By 1845, young William Mason had arrived in Australia, and was possessed of enough capital to set up a station at Samsonvale on the Pine River in the northern districts of New South Wales (now southern Queensland). He seemed to be enjoy good social connections, and that would stand in his stead in the years to come.

Two views of bullock teams working at Samsonvale, on the Pine River.

The settlers of the Pine River area at the time experienced several fatal encounters with the local indigenous people. In 1846, a settler named Andrew Gregor and a workman’s wife, Mary Shannon, were killed by a group of indigenous people. William Mason was on the neighbouring run, and went over to Gregor’s place when he heard of the murders. He was present at Mr Gregor’s burial.

The following year, two sawyers lost their lives. William Waller and William Boller were both speared in a confrontation with the indigenous people of the Pine River. Waller was killed immediately, while Boller endured a long dray ride to Brisbane Hospital, where he died a week later.

Although William Mason lived and worked near the settlers who had been attacked, it was not a frontier clash that ended his station-holding career.

The Struggle to Heal.

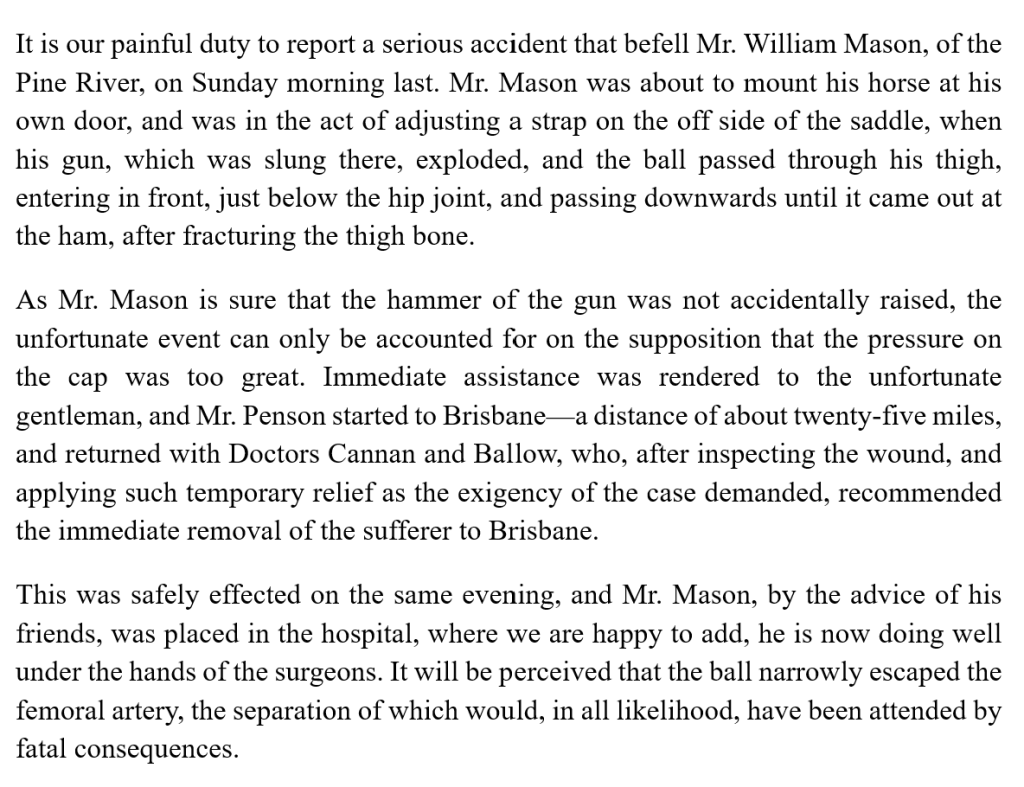

The Register of Cases and Treatment at Moreton Bay Hospital, Brisbane shows that William Mason, aged 30, was admitted on 12 March 1849, suffering fractura.

Dr Ballow noted:

Was fixing a carbine to the saddle when the piece accidentally went off. The ball entered at the upper front of the right thigh passing obliquely downward and backward, shattered the femur and passed at the lower and back part of the upper third of the bone.

The first Brisbane Hospital in George Street, Brisbane. It was originally built in the 1820s as the convict hospital. (This photograph in its various iterations has been identified as from 1850, 1860 and 1865. The doctor in the carriage has been identified as either Dr Bell or Dr Ballow. Given that Dr Ballow died in 1850, and photography was not common in the colony at the time, I’m inclined to believe that this was taken in the early-mid 1860s, and features Dr Bell. This version of the image is from the QUT digital collection.)

Extracts from the medical notes show how painful the recovery must have been.

On 17 March 1849, Mason was showing symptoms of fever. They abated the next day, but “profuse discharge” was noted from the lower wound. He suffered profuse night sweats and poor appetite. Discharge and bits of bone would be coming away for an entire year.

Every day, the doctors and attendants had to carefully move William Mason to remove the bandages, and clean the wound. A cataplasm (plaster or poultice) was applied and bandaged up at least once a day. The main painkiller applied would be – in dire situations – morphia. There were no antibiotics, blood transfusions, x-rays or drips.

Left: Surgeon’s cottage at the old Brisbane Hospital. Right: Rear of old Brisbane Hospital.

After twelve months, William Mason could bear being moved to clean the wound without too much pain. There was no discharge from the upper wound, and Dr Ballow was able to note a “great improvement, both in bodily health and in the mind.”

The fracture itself seemed to be coming together. An improvement would be followed by a setback, but a slight increase in the tea and rice rations seemed to perk Mason up somewhat.

In September 1850, Dr Ballow went out to the Quarantine Station at Dunwich in Moreton Bay to relieve another doctor, who had caught typhoid while treating patients from an infected ship. Ballow himself died of the disease on 29 September 1850. Mason would have felt Ballow’s loss keenly, because the genial and hard-working Scottish doctor had no doubt saved him from death.

Restored to the World.

In January 1853, William Mason, now aged 34, emerged from the Brisbane Hospital to resume his life. He had been there three years and ten months.

I imagine that, at the very least, William Mason had a severe limp. Possibly back and hip pain as well. He was not strong enough to go back to work on the land, and no doubt a long stay in hospital had eroded his finances.

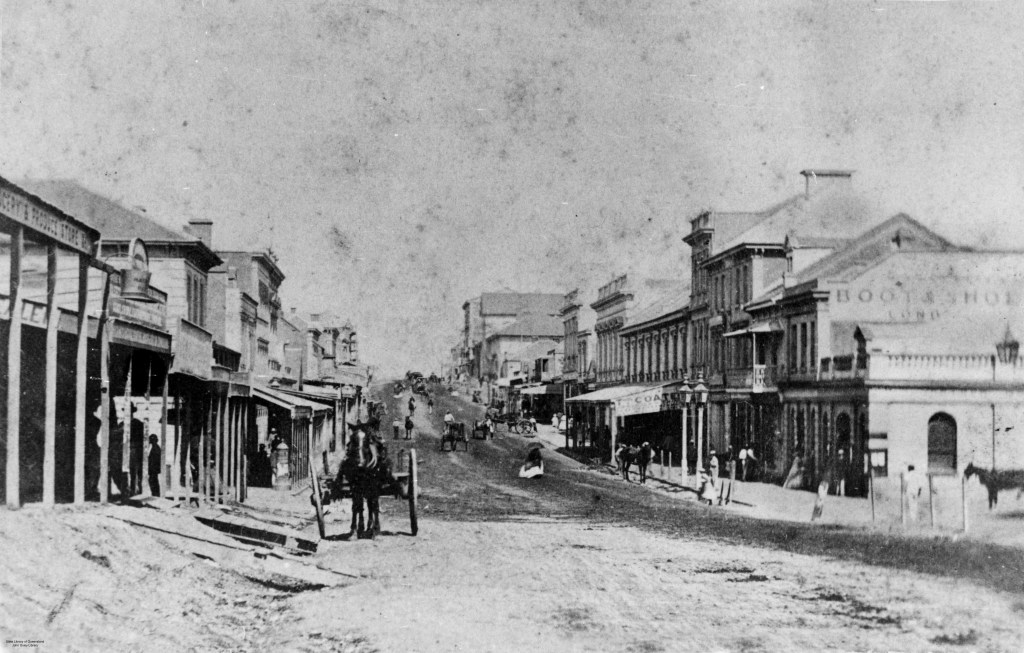

Mason was assisted on his journey back to working life by friends, who suggested (and probably helped finance) a lease on a Tobacconist’s shop in Queen Street Brisbane.

Queen Street, Brisbane as William Mason knew it – in 1859 (top) and in the 1870s (below). The photographs show Brisbane’s progression from a one-horse town to a several-horse town.

That Mason survived, and was able to work at all, was something of a miracle. He knew how fortunate he was to have supportive (and influential) friends, and he made a success of his venture over the following decade.

In 1854, he was called to give evidence in the trial of Dundalli for the murders of Andrew Gregor and William Boller, almost a decade earlier. Mason described the injuries to Gregor, and identified Dundalli as having been present when cattle of his had been stolen before the Gregor murder.

In 1862, William Mason announced that he was retiring from shop-keeping. He became a land agent, operating out of the North Brisbane Hotel in Adelaide Street.

In 1863, his older brother Luke Steward Mason came out from England and joined his brother in the land agency business until his return to the UK in 1874. Both men thrived in the endeavour, and built up large personal property portfolios of their own.

William Mason’s health must have begun to fail around 1876, because Luke Steward Mason returned to Australia that year. On July 25 1879, William Mason died at the age of 60, his lifespan probably reduced by debilitating after-effects of his 30-year-old injury. His brother remained in Brisbane until 1881, clearing up the legal matters arising from the will. Luke Steward Mason died at Grantham, England in 1888.