Mentally Ill Prisoners at St Helena.

John Haslem.

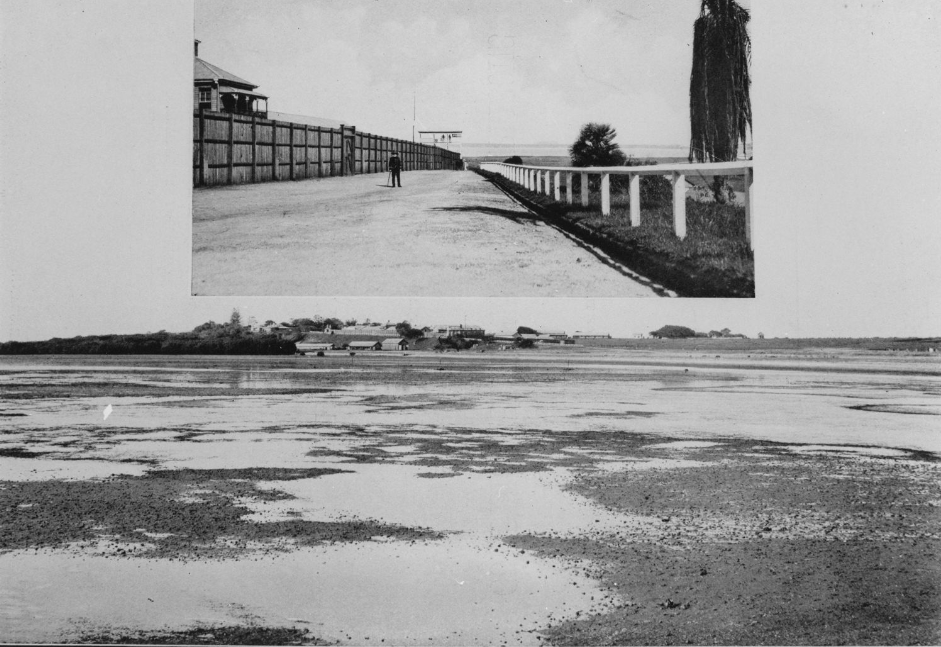

Contemporary views of Muckadilla.

On Monday 20 October 1879, the mail coach was on the outskirts of Muckadilla, a settlement between Roma and Charleville, when a man approached on foot. He presented a double-barreled gun and yelled, “Stop, bail up.”

The coach didn’t immediately stop, apparently to the gunman’s surprise. When it did pull up, he said, “Why didn’t you stop? I might’ve shot you. Is this the coach?” The driver replied that it was indeed the coach. The man said, “I demand a little money for the road, for I am hard up, and I must do this or die.”

This was an unusually meek and polite sort of highwayman. Constable Pettit, who was riding alongside the coach driver said that he might have a little cash. He reached inside his valise and drew out his weapon. As he did that, the robber was distracted by some movement inside the coach, and Pettit was able to overpower the criminal.

As Pettit was handcuffing the would-be thief, he said, “I wish you were Ned Kelly instead of the man you are.” The man replied, “I could have stuck up a party this morning, but I thought they were poor devils like myself, and I let them go. I fully intended to stick up the coach, and I give you great credit for the way in which you took me.”

When this dangerous character was put before the courts, he turned out to be one John Haslem, a native of the Colony, to use the contemporary term for an Australian-born person. At his sentencing (eight years for attempted highway robbery), a journalist described the man in the court.

John Haslem does not present a very formidable aspect. He is about 40 years of age, of medium build and height, with dark hair, whiskers and moustache. He has at first sight an air of simplicity which would lead no one to suppose that any circumstances could arise which would induce him to take so bold a step as to attempt to rob a coachload of passengers in broad daylight. On close inspection, however, the idea is conveyed that the convict possesses a good deal of quiet determination. He appeared rather worn while standing in the dock. He had on a Crimean check shirt, tweed trousers, and a drill Padget coat.

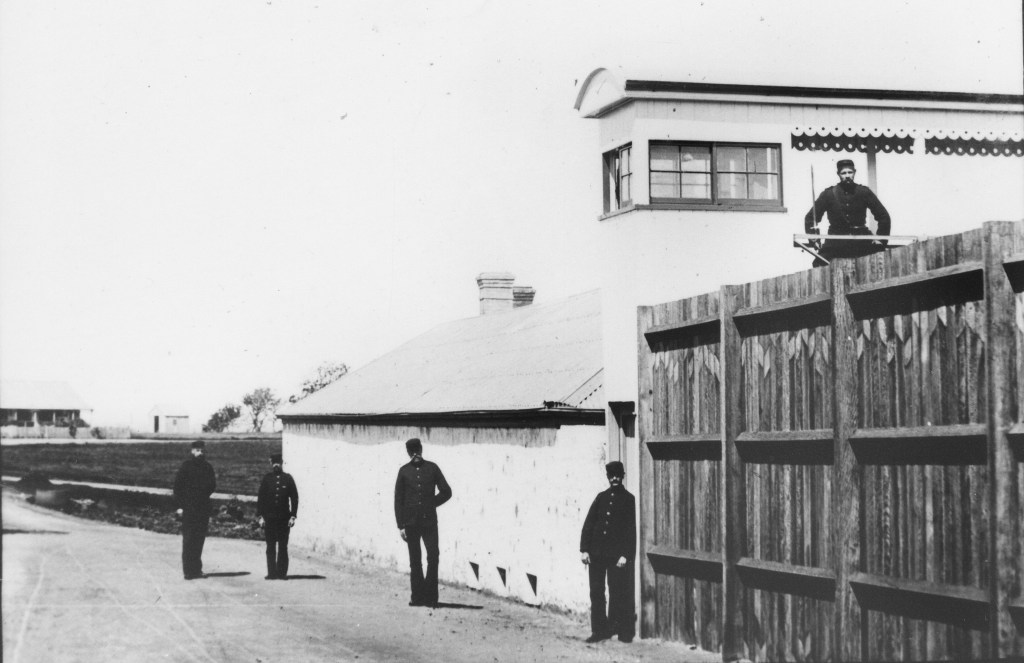

Haslem found his way to the St Helena penal establishment in late 1882, partly, one suspects, because no other prison could cope with him[i]. However diffident he had appeared at his trial, prison discipline caused him to act out. Almost immediately, he was charged with insubordination and obscene language. And it was unusually obscene language for the time.

“Are you the bugger come here to f*** me, and why don’t you speak out, man. You will learn to be bloody well afraid of me here.’ He turned out in a stooping position undoing his boots and said, “here is my a*** for you now. If you don’t like to f*** it, kiss it.”

Haslem developed a particular hatred of a warden named Michael Ahern, and seemed to find any form of surveillance by him an invitation for a volley of abuse and threats of violence. For two years, Haslem swore, threatened and refused to work. For two years, he remained in the probationary cells – when he wasn’t in the “black hole” solitary confinement cells to expiate his sins.

Haslem’s situation became so concerning that someone associated with St Helena wrote an anonymous letter to the Ipswich Daily Standard newspaper. It may have been a sympathetic warder, or possibly someone associated with the Visiting Justice [ii].

Of late, when in the dark cell, he has for days at a time refused food. It is impossible to believe that all this is “shamming” for an ulterior object, for the poor wretch has already gone through ten times greater punishment than if he waited to complete his sentence in an orderly manner.

Haslam is wearing his life out and is now a mere shadow of his former self. I believe that in the beginning of his series of punishments — for, of course, in a gaol there is an imperium in imperio[iii], so to speak — he would try to defend his actions; but latterly, it is said, he comes up to receive his sentences without a word.

Maurice O’Brien.

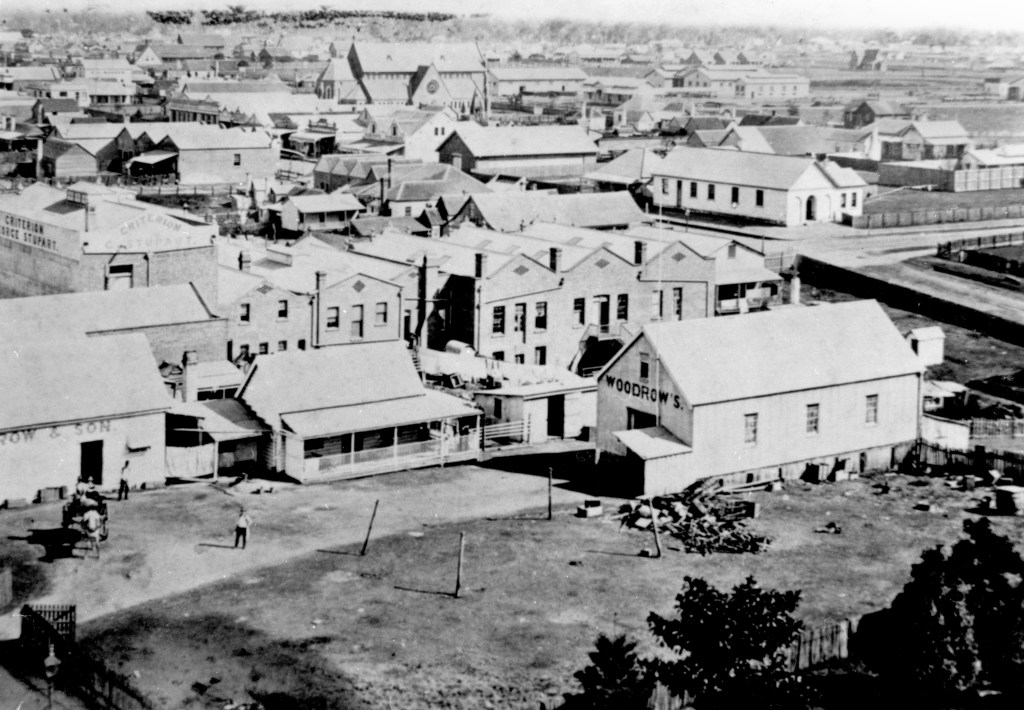

Contemporary views of Maryborough.

Haslem was not alone in troubling the St Helena authorities with his behaviour. In June 1882, an unkempt young man with an American accent entered the Australian Joint Stock Bank in Maryborough, armed with a pistol, and muttering under his breath about “cash.”

The teller at the AJS Bank had a gun, and quick reflexes. He started firing immediately, causing the would-be robber to seek shelter under the counter and beg for his life. Locals, hearing the ruckus, summoned a constable, and the young man was taken away in handcuffs, by then smiling peacefully at the crowds who had assembled near the police station.

Maurice O’Brien was immediately marked as “thought to be insane,” and his case was delayed several times as medical practitioners tried to work out what his condition was.

The prisoner, who is a well-built young fellow, is about 26 years of age, of medium height with rather an abnormal quantity of light brown hair, and short brown whiskers, a description totally at variance with that furnished to the police. He gives his name as Maurice O’Brien, says he is an American, but can’t tell the State he was born in; that he sailed from New York and arrived in Brisbane about four years ago, in an American ship[iv], but cannot recollect her name.

Maurice O’Brien was sentenced to 10 years’ penal servitude in October 1882 at Brisbane. The Chief Justice felt that sentencing him harshly would act as a deterrent to those contemplating such a crime in the future.

O’Brien arrived at St Helena not long before John Haslem. At first, he did his prison work well, but behaved “strangely and childishly, and avoiding the society of others.” A few months in, he became uncontrollable – refusing to work, earning himself time in the solitary “black hole,” and eventually attacking Chief Warden Gimson with a marlinspike. Gimson avoided a potentially life-threatening injury only because he saw O’Brien’s shadow approaching.

The cause of a lot of his disciplinary problems was something that couldn’t be mentioned in the anonymous letter to the Daily Observer. O’Brien masturbated openly and frequently, which of course led to several visits to the Visiting Justice for exposing himself and obscene behaviour. As his punishments increased, he became more aggressive.

The Visiting Justice was concerned enough to order an assessment of Maurice O’Brien’s sanity before sentencing him over the assault on Gimson. O’Brien was taken to Woogaroo, where Dr Scholes observed:

I found a stubborn-looking young man whose general appearance and behaviour indicated a mental condition weaker than the average but who perfectly understood all questions asked and persistently replied to them, “I don’t know.”

Once he betrayed his knowledge of the escape of the prisoners who had absconded a few days before. Through the interview, which lasted some time, he appeared to know much more than he would acknowledge. he showed no delusions. The officers state that he constantly masturbates and this practice will eventually further weaken his mind.

At present I am unable to certify that he is insane and believe that many of his symptoms are feigned though there is some mental weakness.

The prisoner was taken back to St Helena, and procedures were tightened to prevent unauthorised people taking dangerous items out of the sailmaker’s shed. Not long after, O’Brien punched a warden – hard – in the face. The dark cell hadn’t worked, so this time, O’Brien was flogged.

According to the Figaro in June 1884, “ever since, his punishment has remained in probation and exercised in handcuffs. ‘Probation,’ I may explain, is solitary confinement on a low scale of diet, with one hour for exercise in the morning and another at night. In gaol phraseology it is expressively denominated ‘’slow broke’ from the effect it has upon a man’s constitution.” Ultimately, both prisoners were sent to institutions. And eventually died in them.

O’Brien was sent to Woogaroo on 14 November 1884, so mentally ill that he was unable to continue being housed in a prison. He died there in July 1896, of tuberculosis. He would have been around 40 years old but had not been able to communicate his actual age, or where in America he had come from.

In September 1901, John Haslem died of pneumonia and exhaustion in the Toowoomba Asylum, aged 57.

[i] Haslem had been convicted of horse-stealing in Bourke and served just over 12 months.

[ii] The only information I could find about St Helena staff writing to the newspapers was a mention in the Colonial Secretary correspondence of a warden who had used the Penal settlement’s postage account to write a letter to or via his mother. The issue raised was the use of the postage money, and it was not recommended that the individual be dismissed. If that warden had been the person who wrote such a criticism of the management of the prison, he would have been in rather more trouble with the authorities.

[iii] “Empire within an empire”

[iv] There was a Maurice O’Brien aboard the “Scottish Hero,” which seems to track with his account of his arrival.