Convicts who went from Moreton Bay to Norfolk Island.

Edward Doolan’s short life was punctuated by a series of extremely bad decisions. It ended because of one of them. His story is part of a series of posts about the Moreton Bay men who went on to serve time at Norfolk Island. Only a few survived.

Edward Dolan was born around 1808 in County Galway, Ireland. He presumably came from a poor background, having “none” recorded as his educational level when he arrived in Australia, aged 20.

For a young man with limited resources, and, presumably, a desire not to plough or till his native soil, the British Army must have seemed like a good option. Napoleon was dead, and no-one seemed inclined to start another round of catastrophic wars. Dolan joined His Majesty’s 10th Regiment of Foot, hoping for regular pay and some opportunities.

The First Very Bad Decision.

What Edward got was Bellam in Portugal, and presumably he didn’t like it much. He made his first very bad decision and deserted. Too hot? Too foreign? Too much hard work? We will never know. (One hopes that he at least got to march around in the rather fascinating headgear sported by that Regiment before he fled.)

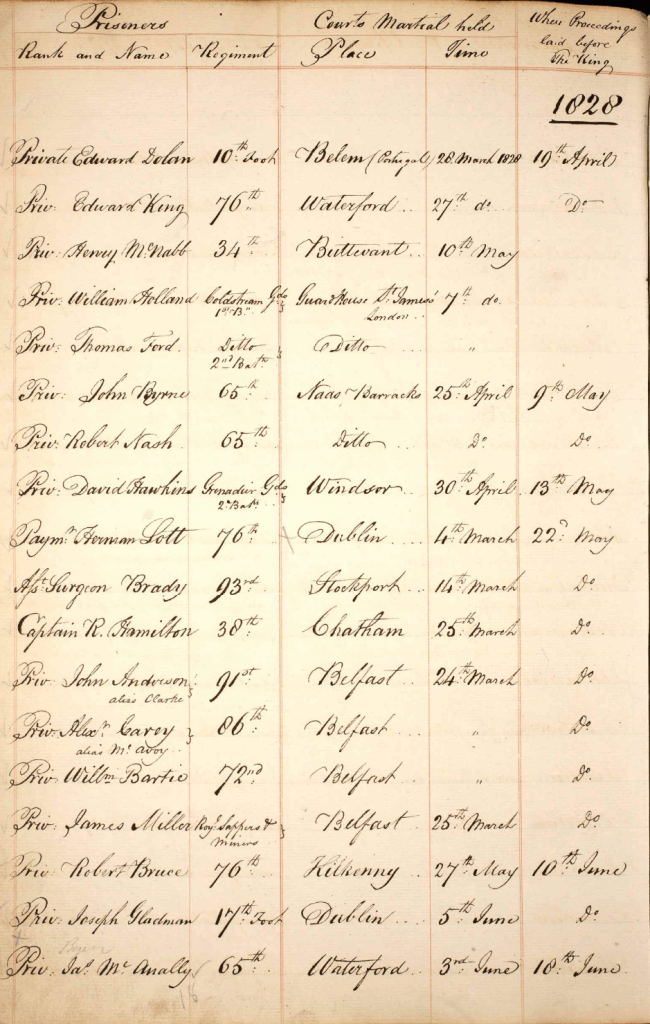

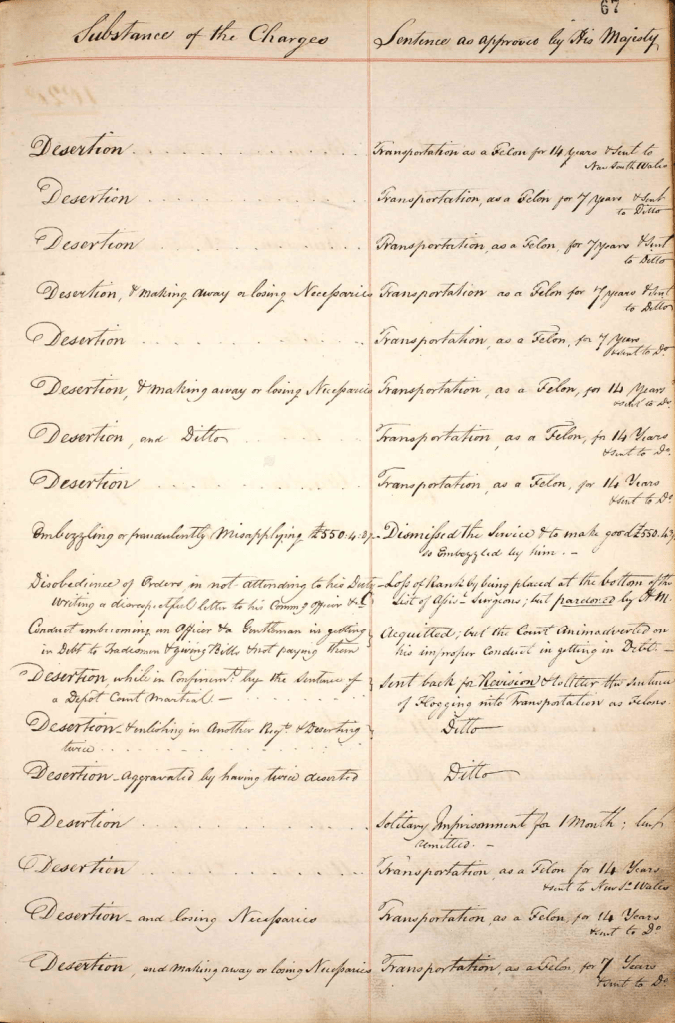

Edward was located and court-martialed in Bellam on 28 March 1828, and his case laid before the King on 19 April 1828. His Majesty approved a sentence that Dolan be transported as a felon for 14 years to New South Wales. Quite a harsh sentence, considering that he wasn’t even charged with losing his necessaries.

In August 1828, Edward Dolan boarded the Royal George as a convict, and arrived in Sydney on Christmas Eve, 1828. His convict indent shows that he was 20, 5 feet 5 ½ inches, with dark brown hair, blue eyes and had a ruddy pock-pitted complexion. The convict chroniclers missed nothing, noting that the little finger of his right hand was crooked. Dolan was sent to Bargo, south-west of Sydney, to be the convict servant of Mr Edward Wright.

For eighteen months, Dolan laboured for Wright, a pernickety settler who kept a detailed journal of the attendance, movements and work of all his convict servants. There was one interruption to Dolan’s service when the young man got drunk and was sent to work on a treadmill for ten days in August 1829. After that rather brutal hangover cure, Edward was straight back at Bargo in Wright’s service until 8 October 1830, when his carelessness caused one of Mr Wright’s horses to drown. A furious Wright brought Edward Dolan before Major Henry Antill, the Resident Magistrate, who sentenced Dolan to be worked in chains for 12 months.

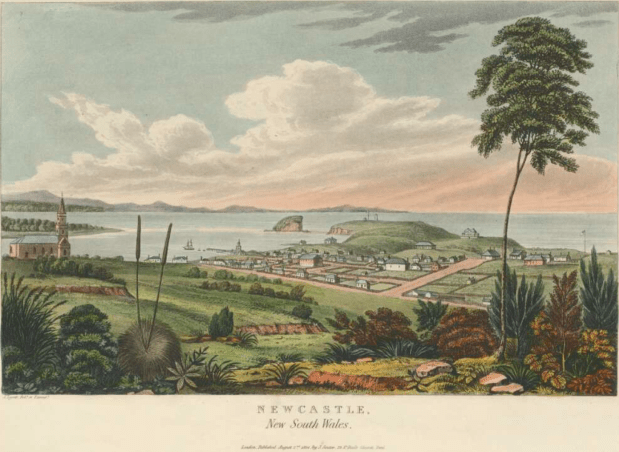

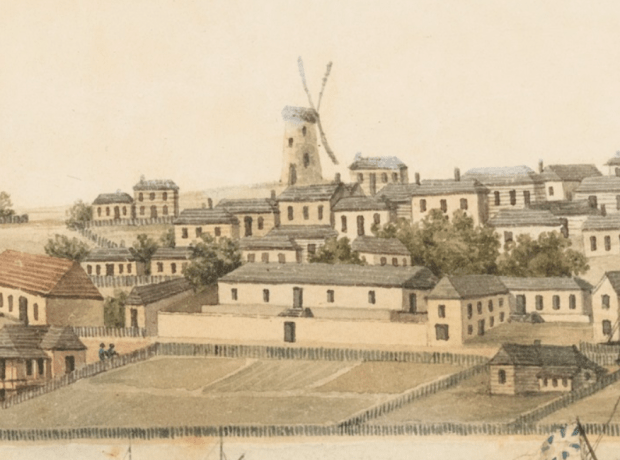

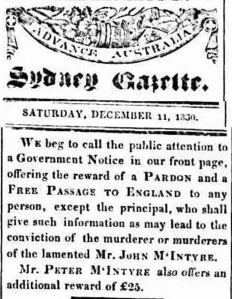

Dolan was sent to Newcastle to serve his sentence in October 1830 and found the place buzzing with the news that a wealthy, but rather tyrannical, local settler named John McIntyre had gone missing. McIntyre was presumed to have been murdered, although his remains had not been found. Various shady characters were in the local gaol under questioning, and it’s probable that Dolan encountered at least one of them in his new environs.

The Second Very Bad Decision.

On 20 November 1830, Edward Dolan made his second very bad decision. He entered the house of Peter Fredericks at Newcastle, and asked Mrs Ann Fredericks, who was alone at home, for some firearms. Ann was a woman with spirit. She asked him what he wanted them for, but he brushed past her without saying anything. Dolan began rummaging around in the household storage. Ann picked up a horn and began blowing it to alert the Fredericks’ workers to come to the house. She marched to the verandah and blew the horn lustily. Dolan came after her and asked her not to do that. He raised his hand, but didn’t strike her, and went back into the house to steal boots, a hat, a shot belt and a fowling piece and walked off. Ann waited for a moment, then began following Dolan. He turned around and gave her back the gun and belt and then legged it.

John Wade, a shoemaker working at the Fredericks’ property had heard the horn, and chased after Dolan on Ann’s behalf, catching him about a mile away. Edward did not struggle and was searched and lodged in the lock-up. He had been wearing the hat and boots, so couldn’t deny the robbery charge. The police also found a silk handkerchief, but it wasn’t part of the robbery at the Fredericks’. No-one claimed the handkerchief, so Dolan ended up keeping it after his trial.

Dolan was taken to Sydney and tried at the Supreme Court for robbery and for putting Ann Fredericks in bodily fear. Ann stated in her evidence, “I was not in the least afraid,” which was probably true. Few burglars ever behaved so timidly, fewer still would hand back a gun and ammunition to the person they’d just stolen them from. However, Edward Dolan was undefended, did not give any mitigating evidence, and received the death penalty.

Edward Dolan sat in Sydney Gaol under sentence of death, and hoping against hope for a reprieve. While there, he met a young Irish woman and was comforted by reminiscing about the old country with her. Dolan gave her the handkerchief by slipping it under the door to her cell, assuming that he would be executed before long, and a keepsake would be nice.

Dolan was convicted in January 1831 and remained at Sydney Gaol for six months before his sentence was respited and he was moved to the Hulk to be transported to Moreton Bay for seven years. That was quite a long time for His Excellency to spend considering whether to commute the death penalty. Death to seven years at Moreton Bay was quite a reduction in sentence. Something had happened.

The Third Very Bad Decision.

Something had indeed happened. Edward Dolan offered up – in desperate hopes of a commutation – information on four men for the murder of John McIntyre at Newcastle in September 1830. Captain Rossi was called on to hear the depositions in the matter and recalled one of the accused men saying something to Dolan, then striking him after his evidence was taken. Rossi couldn’t hear what it was.

The accused murderers were Thomas McGrath, Samuel Ryan, William Steele and Patrick Daley, and Dolan was the “approver,” giving evidence of taking part in the attack on McIntyre, and of witnessing the killing.

Edward Dolan was at last, in August 1831, sent to Moreton Bay. He can’t have liked the place much. He arrived on board the Eleanor on 22 August and absconded on 27 August. He mustn’t have liked the bush around Brisbane Town much either. He returned from absconding on 31 August, having roughed it for three nights.

Dolan gritted his teeth and remained at Moreton Bay until he was sent back to Sydney to give evidence in the trial of McGrath, Ryan, Steele and Daley. This trial would prove his undoing.

The Trial

On December 14 and 15, 1832, Edward Dolan gave evidence in the trial of the four men accused of murdering John McIntyre two years previously.

Dolan spun a tale that had him absconding from a constable in August 1830, on the road between Liverpool and Sydney, and reaching the Newcastle area in about five days.

At Newcastle, he claimed to have met a man named Yorkshire Johnny, who, assuming that Dolan was a bushranger, introduced him to two of the accused, Ryan and Steele. The men decided to rob John McIntyre, using guns supplied by Yorkshire Johnny and his neighbour (wait for it) Paddy the Goose.

The three men met McIntyre’s servant, Daley, who helped them in the conspiracy because “McIntyre was a dreadful tyrant,” and would have a lot of cash on him the following morning. McGrath, another assigned servant, would give the signal that McIntyre was coming down the road.

The victim duly appeared on horseback, and Doolan claimed to have fired the first shot, hitting McIntyre in the shoulder. McIntyre cried out, and the other men fired their guns all at once, killing him.

The dead man turned out to have little money on him, but his assassins divided some of his possessions amongst themselves. Steele took his nice boots, Dolan took the pocket handkerchief, and McGrath took a blue coat. There was no mention of Daley taking anything. After the killing and robbing, the men took the body into the bush and burned it. The following day, the men returned the guns to Yorkshire Johnny and stole some sheep belonging to a Mr Sparke.

Other witnesses were called for the prosecution, and it became clear that there were several people who had been behaving suspiciously at the time of McIntyre’s disappearance. They were Ryan, Steele, Daley and McGrath. The name Edward Dolan came up in witness’ recollections only in relation to the handkerchief at the lockup. None of the witnesses at McIntyre’s establishment mentioned Dolan.

[To my absolute delight, Yorkshire Johnny and Paddy the Goose were real people who lived in the area around McIntyre’s place. Police had searched Yorkshire Johnny’s property and had found no weapons, and nothing to link him with the murderers. Paddy the Goose, however, had a musket and ammunition at his place. Mr The Goose was a former convict, who was not allowed to possess firearms, and who was strongly suspected of harbouring local bushrangers.]

The defendants’ lawyer had cross-examined Dolan vigorously but had not been able to get the man to change any of the details of his evidence. But then Edward Wright was called, along with several servants and some Newcastle police.

Mr Wright, armed with his journal of the convict labourers, blustered into the witness stand. Edward Dolan had been in his employ between August 1829 and 11 October 1830, with the exception of the ten days spent on the treadmill for drunkenness. Dolan had then been sent to work in chains for causing a horse to drown. In other words, Dolan was not at large in August and September 1830, and he was certainly not in the Newcastle district at that time. (McIntyre went missing on 6 September 1830). Mr Wright prided himself on reporting absences from his service, not to mention breaches of discipline. I’ll bet he did.

The prisoners’ defence campaigned vigorously to have Dolan’s evidence struck out. That he was a convict attaint. That he had concocted the story to keep himself out of the hangman’s reach. The Bench heard the submissions but chose not to listen.

There was, it must be said, enough evidence given that implicated some if not all of the prisoners in the disappearance of McIntyre. McGrath was wearing a coat that had been worn by McIntyre, specially tailored by one of McIntyre’s other servants to fit him. Steele had the dead man’s boots on. All were in custody at Newcastle in late 1830, implicating each other and other servants in the crime, when Edward Dolan came in on 20 November for robbing Ann Fredericks. No doubt at some point, Dolan acquired the handkerchief at Newcastle before his arrest. No doubt Dolan heard the tales of Paddy the Goose and Yorkshire Johnny from the other prisoners. He didn’t seem to know any other prosecution witnesses, nor did they know him. And Dolan didn’t say anything until his situation became fatal in January 1831.

The prisoners – Thomas McGrath, Samuel Ryan, William Steele and Patrick Daley – were found guilty of the murder of John McIntyre on 15 December 1832, were sentenced to be executed the following Monday morning, and their bodies to be dissected and anatomised.

That didn’t happen.

The Confession

One of the prosecution witnesses offered up a new confession. Charles James had been a shepherd in McIntyre’s employ, and had shared McGrath’s hut after McIntyre went missing. He had given evidence that he had seen his master’s coat on McGrath on the day McIntyre disappeared. Charles James now claimed to be the perpetrator of the crime itself.

This saved the four prisoners from the gallows until the claims could be verified. James was examined extensively by the Attorney-General, then placed in strict confinement to prevent him communicating with other witnesses or the prisoners. James was taken to Newcastle in February 1833, to verify his story that he had dumped McIntyre’s body in a waterhole, then hidden his watch. No traces were found of the dead man or his possessions.

Edward Dolan remained in Sydney in custody, now afraid for his safety. Charles James was found to be an unsatisfactory but persistent self-accuser. The Attorney-General and the Colonial Secretary investigated the matter and came to some conclusions. The convictions of the four men would stay, but they would not be executed. Edward Dolan had given false evidence, and Charles James was a problem no-one could find a solution to.

The End

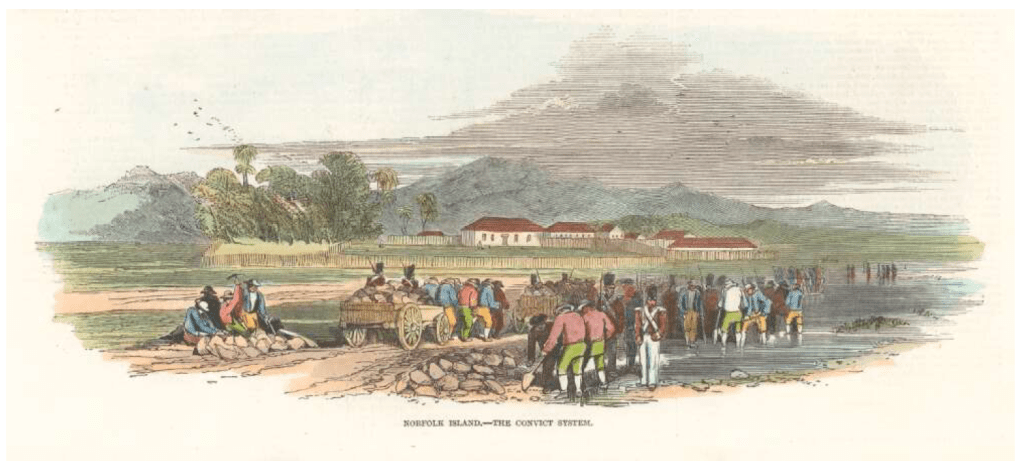

In late February, the Colonial Secretary decided to forward Charles James to Newcastle, without charging him further. On 8 March, Captain Clunie was informed that Dolan “has been forwarded to Norfolk Island instead of being returned to the former settlement to complete his sentence, in consequence of his atrocity in giving false evidence against the above men.”

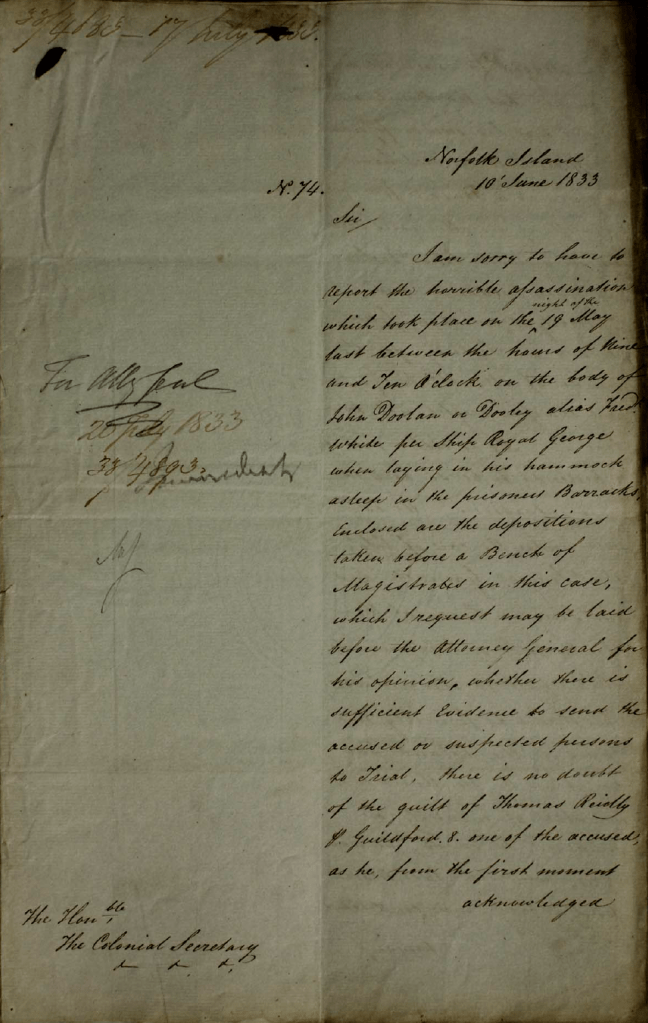

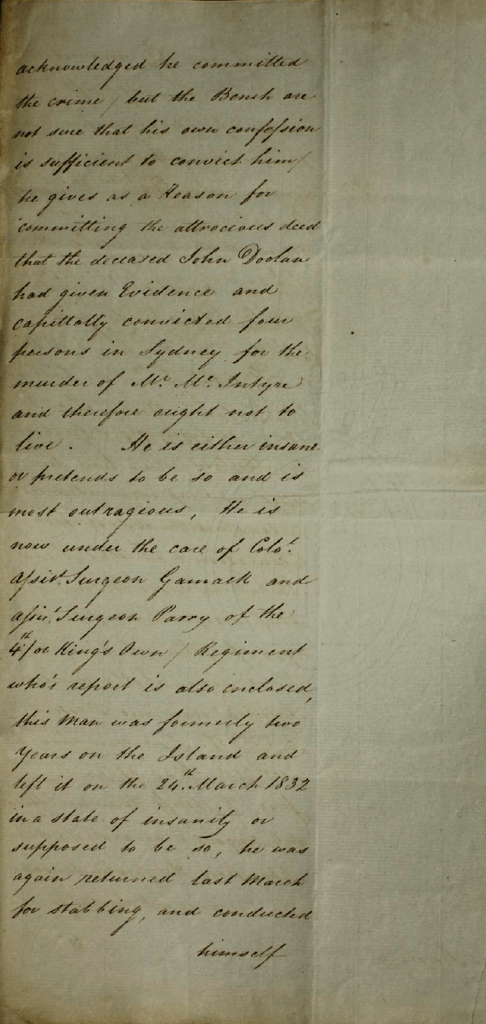

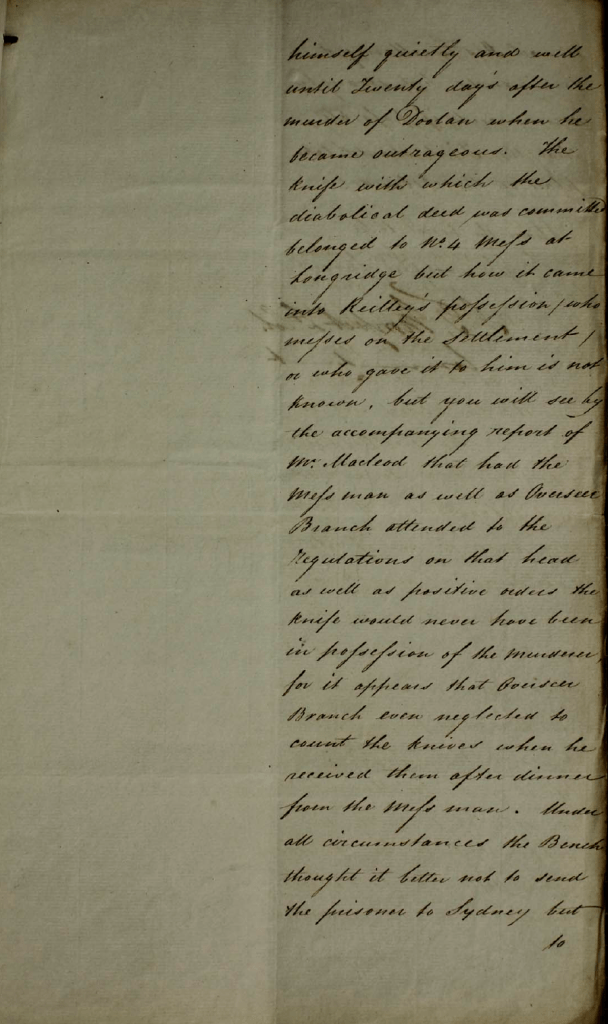

On 8 March 1833, Dolan arrived at Norfolk Island on the Governor Phillip. On 19 May 1833, a fellow-prisoner, one Thomas Rielly[i], stabbed him repeatedly as he lay in his hammock. It seems to have been an attack motivated by the universal convict hatred for informers. On 24 May 1833, Edward Dolan died of his injuries, aged 24. Thomas Reilly was tried and executed for Dolan’s murder.

Edward Dolan was buried in the cemetery at Norfolk Island. Nearly two years after Dolan’s murder, Thomas McGrath was sent to serve out his sentence at Norfolk Island. He spent 10 years there, presumably often passing the cemetery that contained Edward Dolan. It must have been a strange feeling to contemplate his accuser’s silent presence in his life. McGrath left Norfolk Island in July 1845 and received his ticket of leave the following year. He’d done his time for murder.

[i] Thomas Reilly was a fascinating and tragic character in his own right. He was a young Irishman who had seen three of his brothers transported to Australia for various crimes. Thomas Reilly was transported at the age of 16. Reilly reoffended in New South Wales and was given fourteen years’ transportation. When he arrived at Norfolk Island, still in his teens, he was told (incorrectly) by its Commandant, Colonel Morisset, that his sentence was fourteen years in irons.

Reilly had been behaving very oddly for some time, and it depended on who was telling the tale whether he was insane or whether he was play-acting. He gave two reasons for committing the murder (after running around chanting “It was Reilly, it was Reilly” at the time). The first reason he gave – at the time of the attack was that he preferred “being hung out of the way” to being in chains for life. The second reason he gave – at his trial – was that Dolan was a dog (or snitch) who didn’t deserve to live.

The Chief Justice, Francis Forbes, convened a Supreme Court at Norfolk Island to try Reilly, another murderer, and a group of men who’d tried to steal a government boat. Forbes made careful enquiries and had Reilly examined to see if he was sane enough to take his trial. Reilly apparently knew what he was doing, although he acted oddly in Court. He was convicted and sentenced to death, which sentence was carried out on 23 September 1833. It was reported that Reilly danced on the scaffold and gave a speech to the assembled convicts (who were of course ordered to witness his death as an example), telling them to refrain from “eating any more corn bread, they were fools if they did.”

Edward Dolan’s Court Martial Record (General Record of Courts Martial, Home Office, English National Archives).

Letter from Colonel Morisset advising the Colonial Secretary of Dolan’s murder. (4 pages) Norfolk Island Colonial Secretary Correspondence 1833 Part 1 (State Archives of New South Wales)

Could this have given Edward Dolan ideas?