The Eleanor was a trading ship, built at Calcutta in 1821 [i]. She worked trade routes from Asia to England before being contracted to transport an unusual group of convicts to Australia – hard-working, honest men who had taken part in industrial action.

The Machine Breakers

“The men per Eleanor were landed on Monday last and appeared a strapping healthy set. It will be remembered these men were transported as rioters and machine breakers, and will no doubt be an acquisition to the settlers, as they are all farming men.” The Sydney Monitor, 20 July 1831.

Two of Eleanor’s 1831 voyages were memorable. On 15 February 1831, she brought 136 Machine Breakers to New South Wales.

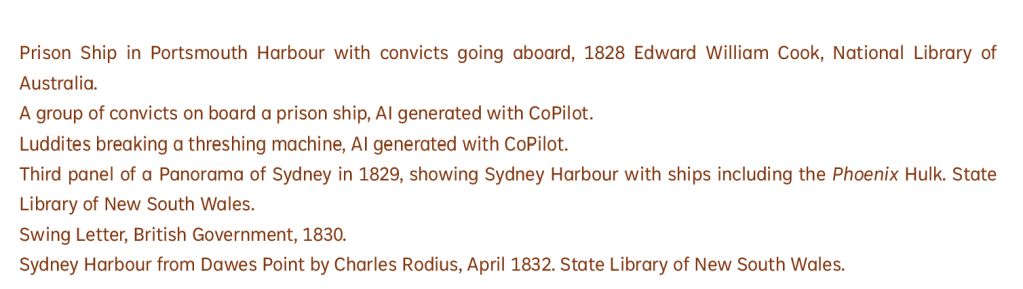

The centuries-old agricultural labouring system of England was transformed during the Georgian period. In the 1810s, weavers and textile makers began a series of protests against the factory owners whose adoption of labour-saving machines threatened their work, and by extension, their existence. These workers were followers of a probably fictional character named Ned Ludd and were given the deathless nickname of Luddites. Violence, arrests, executions and transportation ensued.

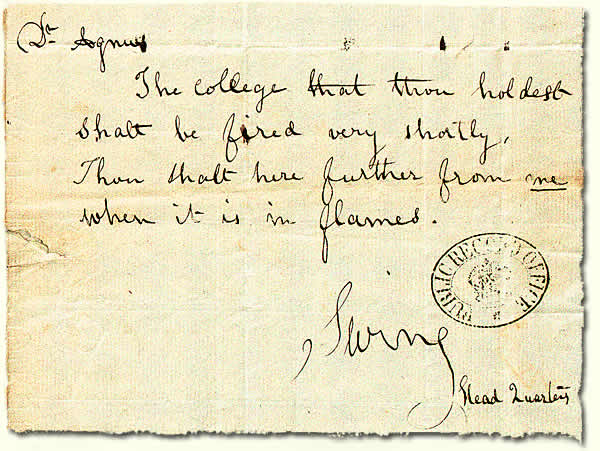

In 1830, another wave of rural labour agitation came in the form of Swing Riots, named after the fictional leader of the movement, Captain Swing. Threshing machines were destroyed in raids on southern and eastern counties in late 1830, earning the rioters the nickname “machine breakers.” The authorities responded in much the same way as they had in 1811. Violence, arrests, executions and transportation again ensued.

The machine breakers were convicted at special Gaol Delivery sessions throughout southern and eastern England. For those to be sent to New South Wales on the Eleanor, the voyage to Sydney was peaceful. The ship was well-provisioned, and the convicts were an unusually healthy and well-conducted group[ii]. The Reverend JCS Handt was a cabin passenger, on his way to minister to the indigenous people of Australia[iii].

The Quick Turnaround.

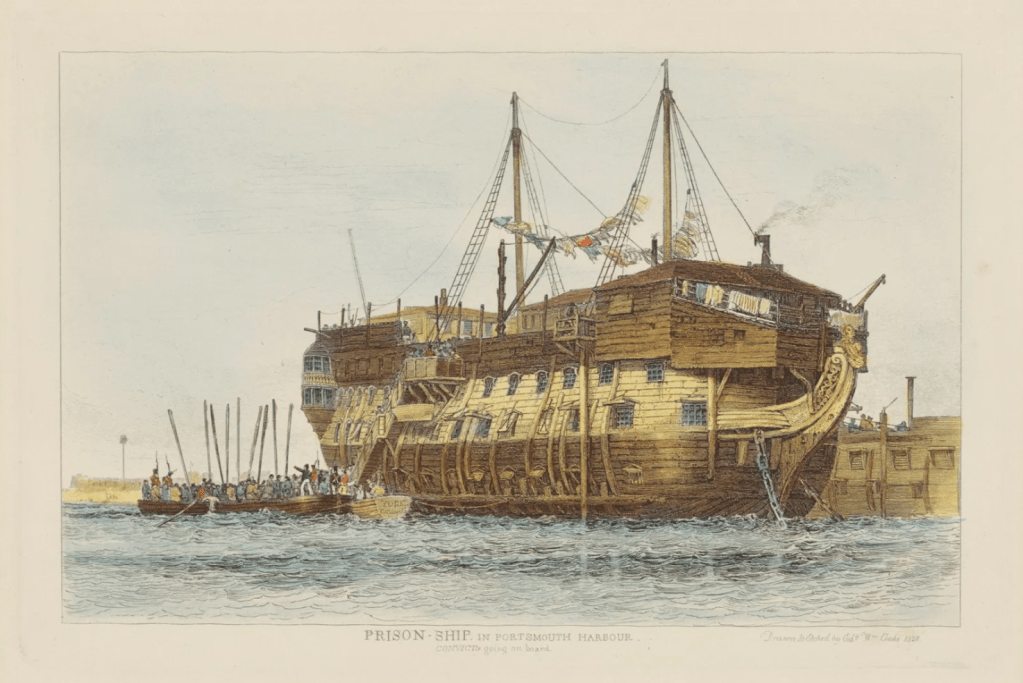

Sydney Gaol and the Phoenix Hulk were bursting at the seams with convicts requiring secondary transportation – that is, convicts who had reoffended and were ordered to be sent to penal stations, particularly that of Moreton Bay. A large ship, fitted out to transport prisoners, was required quickly. The Government of New South Wales contracted with Eleanor’s owners to take 169 prisoners to Moreton Bay.

The Eleanor had arrived in Sydney on 26 June 1831, and the machine breakers on board were mustered and assigned to their employers on 1 July. They had gone from agricultural labourers fighting against mechanisation in one country to indentured rural servants in another.

The ship had to be cleaned, checked, fitted out and stocked with rations. The crew, the guard formed by the 17th Regiment of Foot, and the prisoners all had to be victualled – to receive daily rations of food according to their station in life. The Commissariat in Sydney oversaw the supply of all items necessary for the voyage, as well as the stores required for the settlement at Moreton Bay.

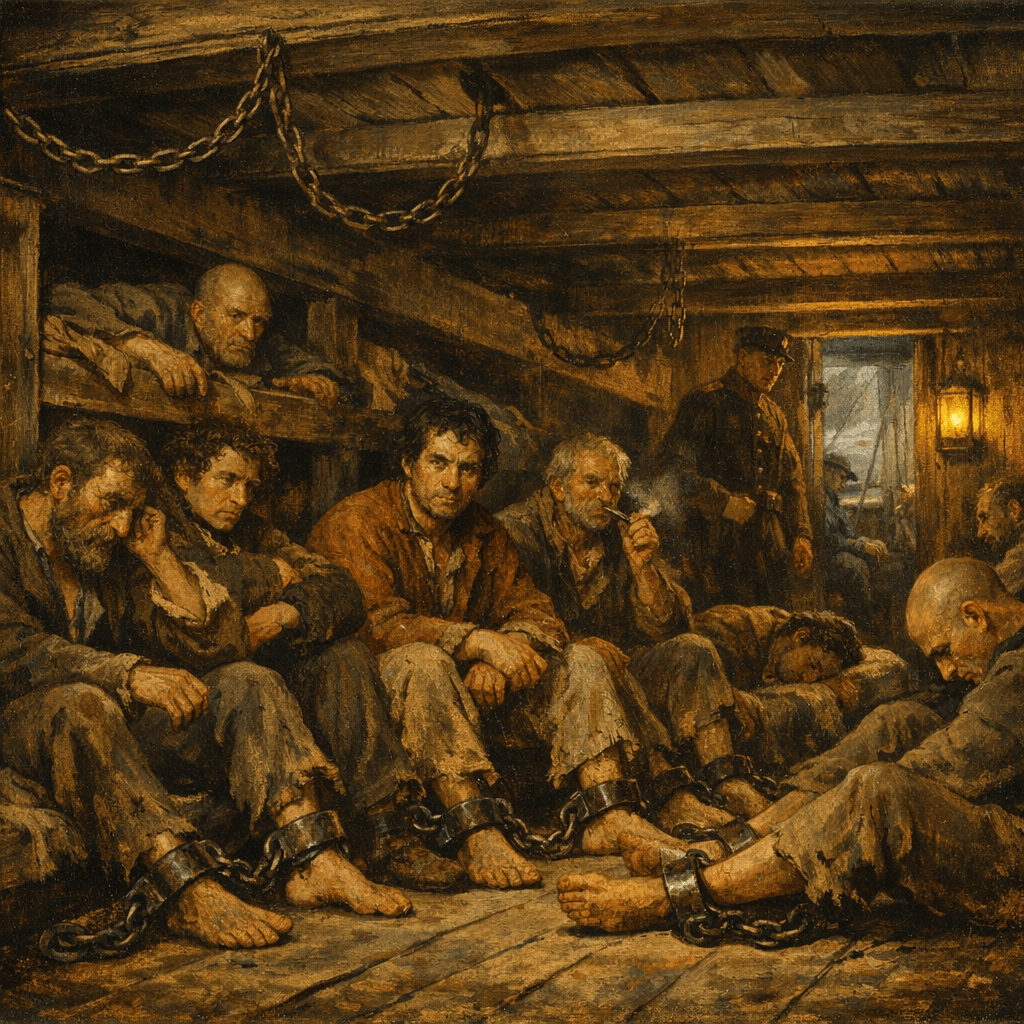

On 30 July 1831, the prisoners were moved from the Phoenix Hulk to the Eleanor and lodged in chains in the prison section to depart on 1 August. These convicts had been found guilty of an extraordinary variety of offences. The most striking were “stealing 63 lbs of beef and using bad language,” “castrating a bull without the consent of its owner,” and “mutinous, turbulent, insubordinate, and threating the life of an Overseer.” On the other end of the scale were men who stole cheese, canvas and the clothes of fellow prisoners.

A mixed group of repeat offenders, including some men who were absconders and others who had threatened or committed violence. The majority had been servants or labourers, a few had been in the armed forces, as well as some artisans (pearl button makers etc) and one surgeon[iv].

The first day on board the Eleanor was fairly quiet. The convicts had brought their own rations for the first day with them and were as content as they could be in the circumstances.

“If we can do with that small ration, we can do without any.”

On 1 August 1831, the Eleanor was still in harbour, and the prisoners began to complain that their new, shipboard rations were short. Four ounces of beef and four ounces of bread were allotted to each prisoner to sustain them for 24 hours. The prisoners knew that there had been a recent increase in their rations ordered by the Governor.

As the small meals were being handed out, around midday, the men grew restive and made their feelings known to the guards. Some refused to take their rations in protest. This created its own problem – rations were sent to the prisoners in sequence. If the first group would not take their all their rations, none of the following groups could receive their food.

According to one witness, the ship’s chief mate told the soldiers, “Shove it in to them and if they won’t take it have them out one by one and shoot them![vi]” The soldiers dispensing the rations decided to place a bag of hard biscuits inside the hold and lock the door.

When the prisoners saw that the delivery of rations was being suspended, there was a rush towards the biscuit bag. Behind the locked door. All of the prisoners were in leg irons. This so alarmed the guard that a cry went up of “Stand to your arms!” and shots were fired into the prison hold. Two men died. Two were injured.

“For God’s sake don’t fire! We are not making any disturbance.”

One of the prisoners, Thomas Taylor [viii], recalled another prisoner shouting that to a soldier, who was aiming his piece directly at a man who was lying in a berth. The soldier shot the man anyway.

Such was the general panic that no-one knew who shot the second man to death or injured the other two men. Captain Deedes ordered the soldiers to cease firing.

The prisoners fell quiet quickly in the wake of the shootings (understandably), and the dead and injured men were brought up on deck. The two dead men had been shot in the head. The injured convicts were taken to the hospital, where they eventually recovered.

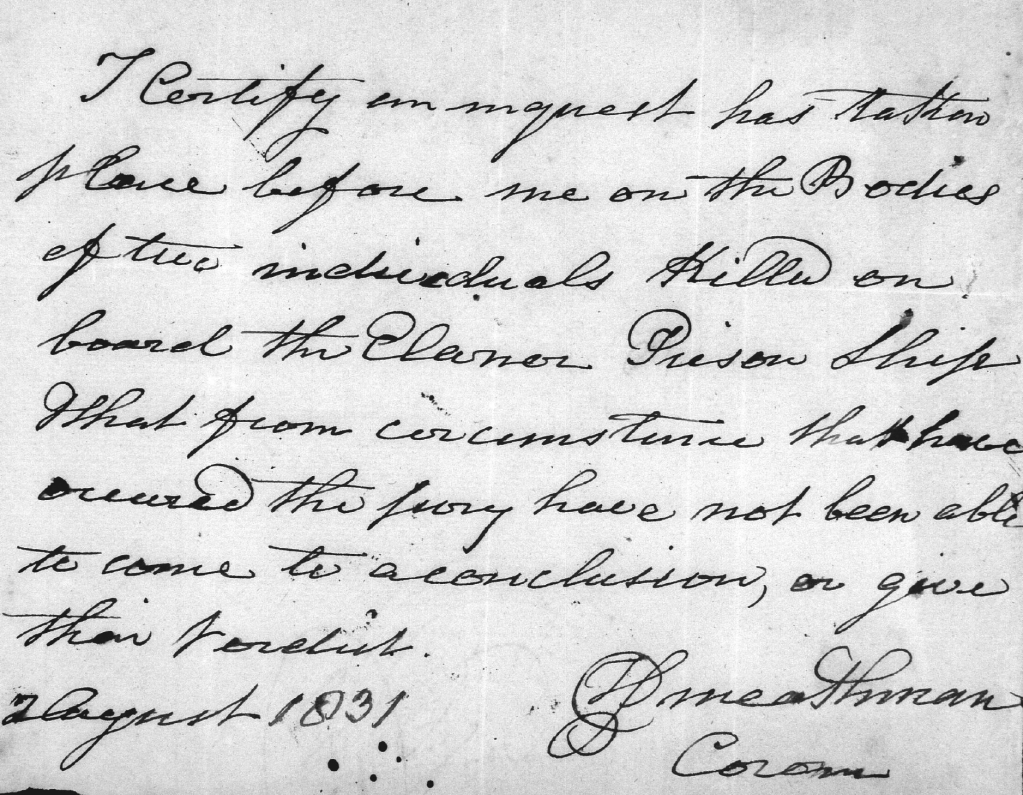

Inquiries had to be held. One was the official coronial inquest into the deaths. The other was an investigation into the supply and distribution of rations to the prisoners. The inquest was convened quickly – the bodies were still on the deck of the Eleanor, and below decks there were over 100 convicts to transport to Moreton Bay.

The Extraordinary Inquest.

Day One.

The Coroner for Sydney was one Major Charles Thomas Smeathman (1774-1835), a man with a distinguished military past, and highly regarded in the colony. At 5 pm on 1 August 1831, he received a message to hold an inquest immediately on two men who had died on board the Eleanor. A jury of respectable townsmen assembled at the Australian Hotel, were sworn in by Major Smeathman, and everyone proceeded to the ship, berthed on the North Shore.

On reaching the deck, they observed the bodies of two men, who had the appearance of having died from gunshot wounds to the head. The state cabin was used as the venue for the inquest, and witnesses began giving evidence. That was the last reasonable thing that would happen at the inquest for several days.

The Coroner’s first direction to the jury had been “that they must return a verdict of justifiable homicide, that they would go on board, take a view of the bodies, cause them to be thrown overboard, and return immediately to give their verdict.”

That the jury refused to do. After the lengthy first sitting on the night of August 1, the jury could not agree on a verdict. This irritated Major Smeathman no end. He agreed, grudgingly, to adjourn the inquest until the next day.

Days Two and Three.

The Coroner opened the second day’s sittings with a lecture about wasting the court’s time. Edward Lee rose to express the concerns of several of his fellow jurymen about the Coroner’s opening instruction, not to mention what they considered his hasty, incomplete depositions. Might the jury also hear the evidence of the prisoners? Could the evidence be taken again to ensure that nothing was missed?

Major Smeathman responded that he could not possibly comply with their request – any evidence taken from men under double and treble criminal sentences could not be received.

Mr Lee reminded him that they were there to render an impartial verdict according to their consciences. Other jurors voiced their concerns, and after what the Monitor called “a long dispute,” the unhappy group returned to the Eleanor to examine witnesses.

The evidence of the “acceptable” witnesses – the military and crew – was taken. Captain George Deedes stated that he was watching the meals being served, heard a “rush” from the prison, and called out to the military to stand to their arms. He heard several shots fired and called out an order to cease fire as soon as he heard the gunfire. Corporal Fitzpatrick deposed that he heard a disturbance, took his gun and fired it into the prison through the bars. Corporal Wheatley heard a commotion and some shots fired. He hadn’t fired, but he had handed ammunition to Fitzpatrick. Private Sullivan did not fire but heard firing. All the military witnesses assured the court that they believed the prisoners to have been in a “state of mutiny,” and that the use of arms had been necessary.

After a “violent dispute between the Coroner and the Jury,” Major Smeathman agreed to hear, but not swear in, some convict witnesses. The first convict witness brought up was a Thomas Turner, who admitted that he was under sentence for an unnatural crime[ix]. The jury had no hesitation in refusing his evidence.

The next convict witness, Thomas Taylor, gave an account of the prisoners receiving short rations, and the discontent it caused. He recalled that the biscuits were “stowed in the prison,” and men scrambled for the biscuits. He heard Deedes call out “stand to your arms,” then saw a soldier draw near to the prison, load his gun, and fire it directly through the bars at a man in his berth.

The Coroner grudgingly accepted that he believed Taylor’s word and asked him if there was a “row or tumult” at the time. Taylor said, “Far from it,” adding that there were worse rows daily on the Phoenix Hulk, and they were easily settled. “There was no mutiny or anything like mutiny,” in Taylor’s words.

Another prisoner, William Barnes, recalled a soldier aiming deliberately at one of the men, so deliberately that there was time to plead for his fellow-prisoner’s life, and the soldier to say, “I will have you!” before the shot was fired.

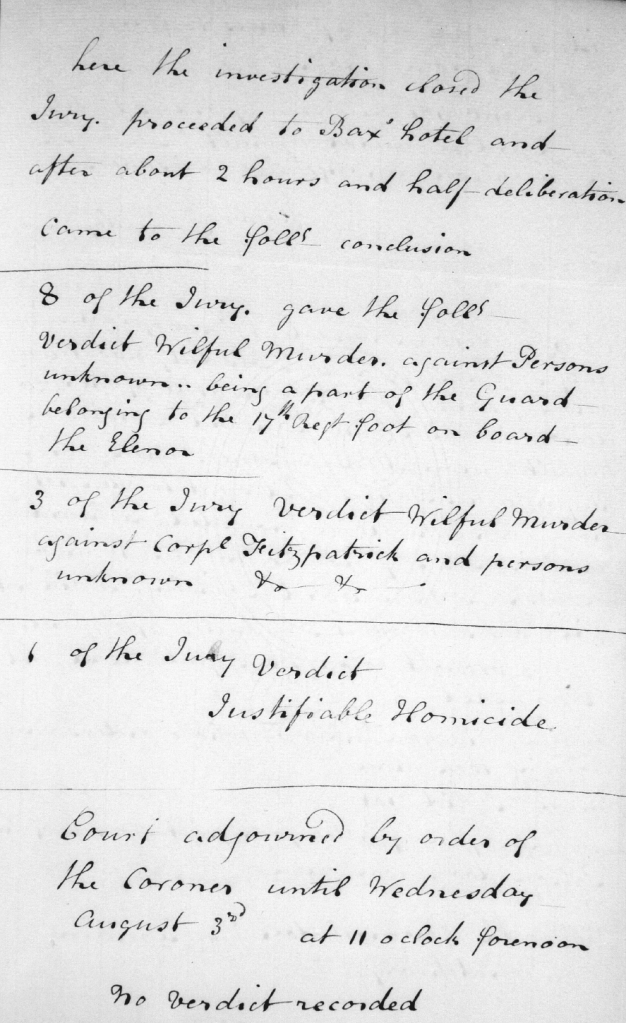

At the end of the witness examinations, on the night of Tuesday 3 August, Major Smeathman and the jury left the ship and the jury retired to the Australian Hotel to deliberate. The jury returned with sealed verdict letters. Eight jurors had returned a verdict of wilful murder by person or persons unknown. Three had returned a verdict of wilful murder by Corporal Fitzpatrick and other persons unknown. One juror returned a verdict of justifiable homicide.

The Monitor reported that “an altercation ensued” between Coroner and Jury, and the case was adjourned to Wednesday 4 August 1831. The bodies were still on board the Eleanor.

Day Four.

On Wednesday 4, Coroner Smeathman offered a legal olive branch to the jury – he had taken advice, and dash it all, wouldn’t you know – he could swear in prisoners to give evidence after all. Who knew? The prisoner witnesses were sworn and gave the same evidence. Then the Chief Mate of the Eleanor, Mr Tickell was brought in on a summons and gave terse evidence. He denied that he had shot anyone, a suspicion that had arisen in the minds of the jury, although he had been armed. He denied that he suggested shooting the prisoners who refused the rations. He had not seen the scale of rations to be allocated.

The jury retired, having been again instructed to return the unanimous verdict of justifiable homicide. They returned with the unanimous verdict of manslaughter by person or persons unknown, and handed it to the almost apoplectic Coroner.

At least, the verdict of twelve respectable citizens had the effect of permitting the authorities to remove the bodies from the deck, where they were, mercifully, given a proper burial on land.

The Dead Men.

The reason I haven’t named the two men killed on board the Eleanor on 1 August 1831, is that it was incredibly hard to find out who they were. Their names were not considered important enough to go into any of the official documents of the inquest. The newspapers did not bother to give their full names, calling one man “King,” and the other “Deane,” “Dean”, “Bean,” or “Beane.” At least they got the surname of Mr King right.

After a lot of cross-referencing and back-tracking, the men killed had been Henry King and Thomas Behan.

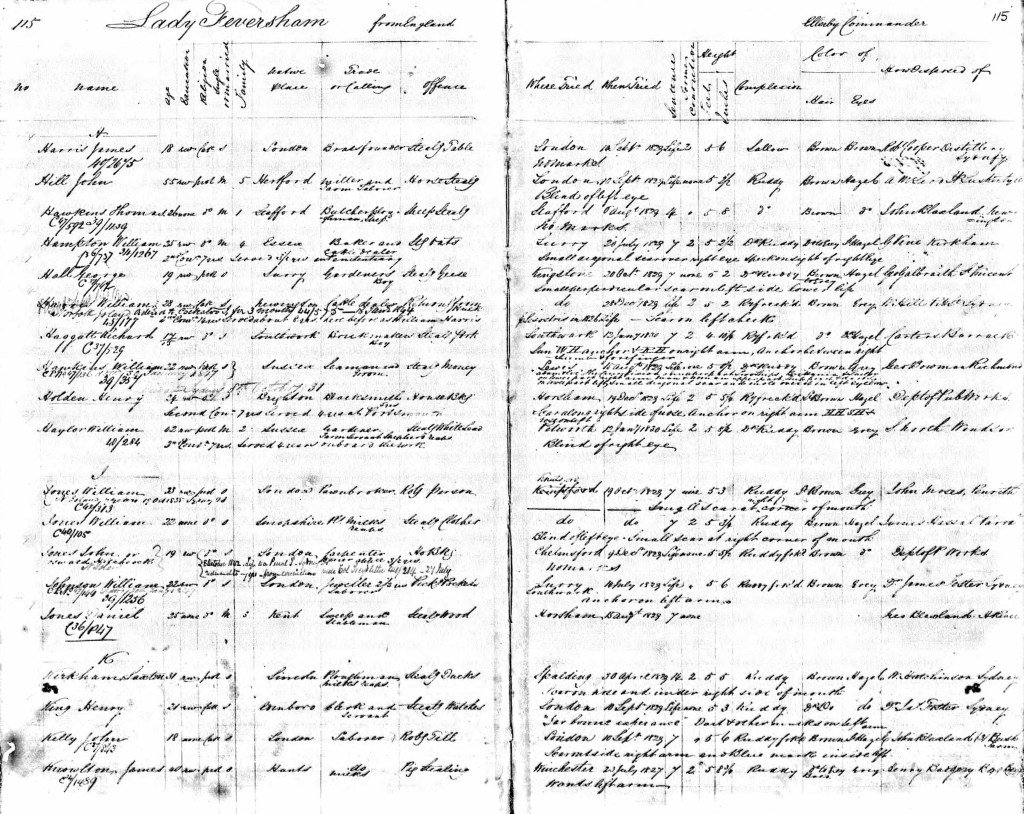

Henry King, aged 22.

Henry King was a 22-year-old single man, who had been born in Edinburgh around 1809. King was well-educated and from a good family. In 1829, Henry was staying with a watchmaker named Charles Weiland and his family. Around eight days into Henry’s stay, Weiland’s son alerted him to some missing watches and a missing lodger. The watches were traced through pawnbrokers, and the pawnbrokers identified Henry King as the seller. The watches were valued by Weiland at a total of around £87.

Henry King was sentenced to death at the Old Bailey in 1829, with a recommendation to mercy from Weiland, on account of the lad’s good family and no prior history. He was transported to Australia on the Lady Feversham. He arrived in July 1830.

Sadly, he didn’t learn the whole crime-doesn’t-pay lesson and was brought before the Supreme Court for breaking and entering in September 1830. His sentence was converted to penal servitude at Moreton Bay. King spent time in Sydney Gaol, then the Phoenix Hulk, before being put on board the Eleanor for Moreton Bay nearly a year later.

Henry King had been lying down in his berth when the soldier had fired at him through the bars. William Barnes called out, “For God’s sake don’t shoot King! He is a very quiet man,” as a soldier (probably Corporal Fitzpatrick) loaded and aimed directly at him. In his evidence, Barnes stated that King was “the gentlest man in the Hulk.” The shot that killed Henry King was the last one fired by the military on board the Eleanor. Henry King was buried at St James’ Church of England, Sydney.

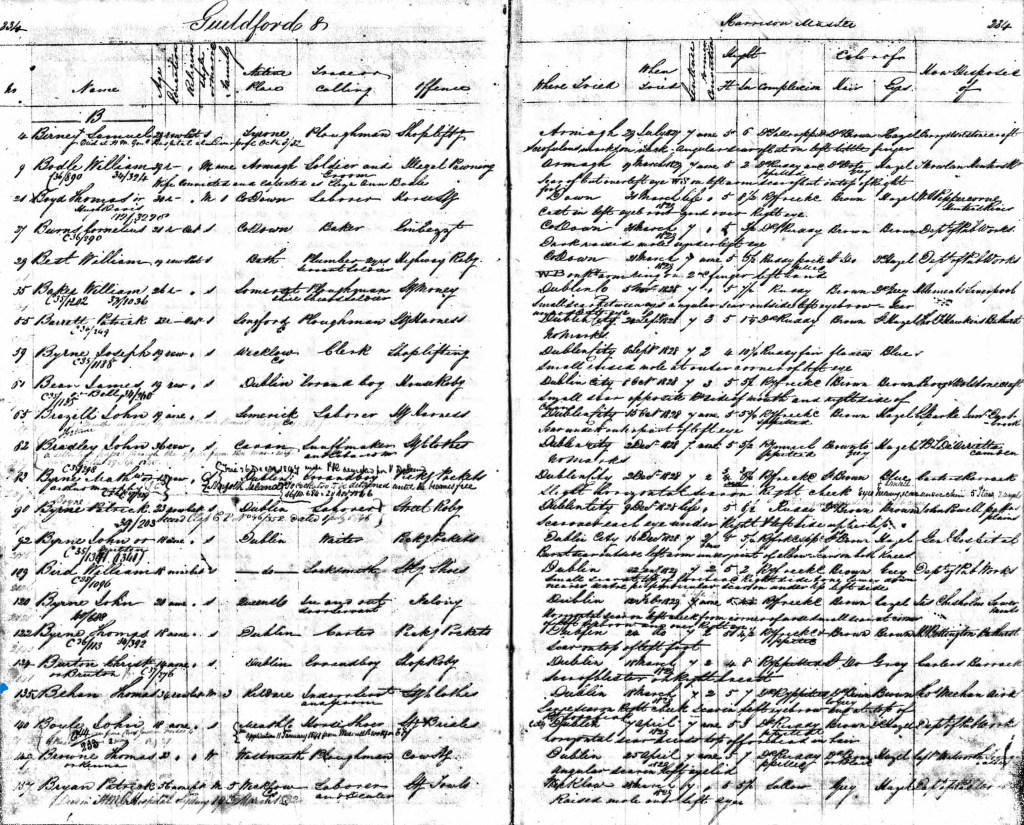

Thomas Behan, aged 37.

Kildare native Thomas Behan was transported on the Guildford in 1829 after being convicted at Dublin for stealing clothes. Behan was a 37-year-old married man, with two children, who had worked as a groom and indoor servant. When he arrived in New South Wales, his dark brown hair was already turning to grey. He was described as stout, 5 foot 7 inches tall, with a ruddy, freckled and pock-pitted complexion and brown eyes.

Thomas Behan reoffended at Liverpool by stealing in a dwelling house and was given two years’ transportation to Moreton Bay in July 1831. He was convicted on 8 July 1831 and was killed on board the Eleanor on 1 August 1831.

Apart from no-one mentioning his correct name in newspaper reports of the shooting on board the Eleanor, no-one seemed to know whether he was shot accidentally, and by whom. Perhaps he was just in the wrong part of the prison when the guns went off. He was also buried at St James’ Church of England, Sydney. [x]

What really concerned the Government.

The minor matter of two human lives aside, the Government had concerns. Real, pressing concerns. The supply of rations. Were the rations too small? Was the Commissariat Office to blame? Was the Captain? The Chief Mate? Had the ration card been supplied to the Eleanor with the goods? If not, why not?

Letters flew about, as if alarmed, between the Colonial Secretary and the people in charge of various things. Major Laidley of the Commissariat Office penned five. John Nicholson of the Master Attendant’s Office wrote four. Attorney-General John Kinchella gave two opinions. Sherriff Cornelius Prout wrote twice. Messrs Looker and Arnold supplied reports. Not about the two dead men. About rations and procedure.

On Saturday 6 August 1831, with Henry King and Thomas Behan off the deck, and given a Christian burial, and the two injured convicts doing nicely in hospital, a panel assembled aboard the Eleanor to find out what happened with the rations.

Superintendent of Police Rossi, Police Magistrate Charles Windeyer and Master Attendant John Nicholson took the evidence of various people from the Commissariat Office, the crew of the ship, and the military. In the process, it was discovered that Chief Mate Tickell did not have access to the bill of rations (and quite frankly wasn’t interested in finding it), the Commissariat had delivered the bill of rations the day before the convicts commenced them, and that Captain Cock had (a) received the bill of rations in time, (b) shoved it in his log and forgotten about it, and (c) lied about it or failed to properly recollect it.

“We cannot but come to the conclusion that the Master of the Eleanor, Mr Robert Cock, has been exceedingly neglectful in not notice the stipulation of his Charter Party and not giving proper directions to his officer for the due delivery of the provisions.” F Rossi. In other words, the convicts were supposed to have been given much better rations, and Cock and Tickell should have known or cared about it.

The combination of this neglect, and military officers who mistook a scuffle behind prison bars for a mutiny and opened fire cost Henry King and Thomas Behan their lives. The Coroner’s jury had recommended that the depositions of the inquest be referred to the Governor, along with their concern that certain military officers might have been guilty of murder or manslaughter. That didn’t happen, but at least perhaps, more care would be taken when handling provisions.

The Eleanor arrived at Moreton Bay with the prisoners and stores on 22 August 1831. Two deaths and two investigations had only delayed the voyage by a week.

[i] In 1841, Eleanor was used just once more as a convict transport – taking 15 prisoners to Van Diemen’s Land in 1841. In 1842, at Alleppey, a load of cotton on board her caught fire, and she was destroyed.

[ii] The machine breakers were mostly in their 20s and 30s and had lived healthy outdoor lives before they became protestors.

[iii] The German Mission at Nundah was one of the main outcomes of his missionary activities.

[iv] The surgeon convict was one Richard Davison Claringbold, who had arrived in 1818. He must have been a striking figure on the Eleanor – 36 years old, six feet tall, slender and with brown hair, grey eyes and a dark complexion. He’d been convicted of forgery in Kent in 1816 and was respited from the death penalty to transportation for life. He had reoffended by stealing a load of shingles and was on his way to Moreton Bay. He served his time, then was convicted again for “pilfering the property of the Governor,” before settling down, marrying, and eventually dying at Stanthorpe in 1856.

[v] Quote from one of the prisoners at the inquest.

[vi] That’s the polite version of the story. Another prisoner claimed that the first mate said, “Those that refuse the ration, take the buggers out one by one and shoot them.”

[vii] Quote from a prisoner in evidence at the Inquest.

[viii] Thomas Taylor was a grocer from Warwickshire who had been convicted of embezzlement both in the UK and in New South Wales. He seems to have been a genial and articulate character and was permitted more time to give evidence than other “twice convicted felons” who had also witnessed the events. He died in Moreton Bay Hospital in December 1831.

[ix] Bestiality, it turned out.

[x] Both men had been Roman Catholic. At least they were given a decent burial in consecrated ground, rather than being tossed overboard as Major Smeathman had suggested.